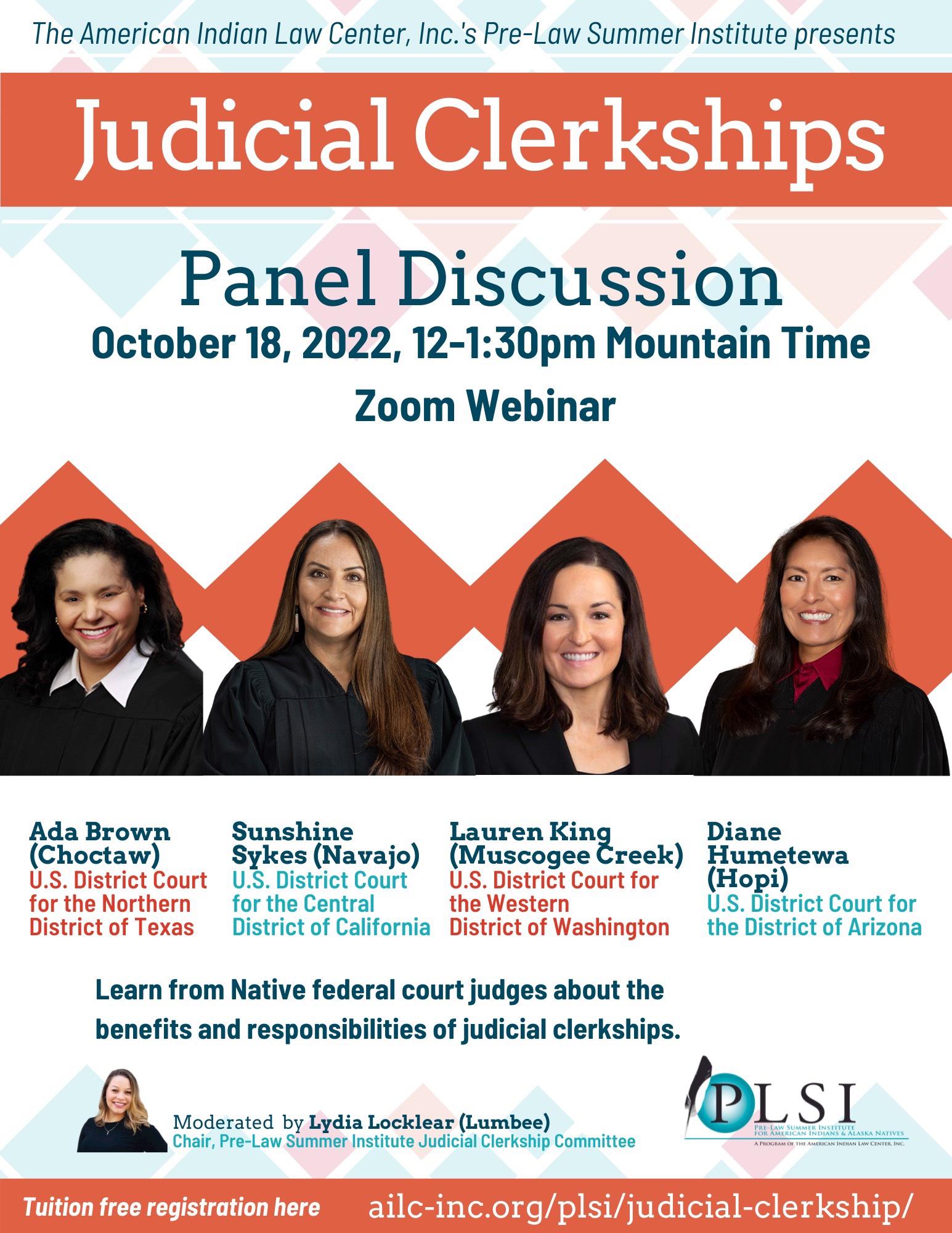

Updated PLSI Judicial Clerkships Panel Discussion Info

Conference details here.

Register here.

Description:

Join ACS for our Annual Supreme Court Preview, part of our observation of this year’s Constitution Day. After the seismic decisions handed down last Term, all eyes will be on the Court this fall to see what may come next. The Preview will feature a diverse group of constitutional and legal experts offering their insights into the upcoming Supreme Court Term that begins on October 3rd.

Welcome Remarks

Russ Feingold, ACS President

Speakers

Adam Liptak, Supreme Court Correspondent, The New York Times (moderator)

Deborah Archer, President, ACLU; Professor of Clinical Law and Co-Faculty Director of the Center on Race, Inequality, and the Law, NYU School of Law

Jonathan Diaz, Senior Legal Counsel, Campaign Legal Center

Kent Greenfield, Professor and Dean’s Distinguished Scholar, Boston College Law School

Wenona Singel, Associate Professor of Law and Director of the Indigenous Law & Policy Center, Michigan State University College of Law

Shoba Sivaprasad Wadhia, Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; Samuel Weiss Faculty Scholar; and Clinical Professor of Law, Penn State Law

Register here.

Description:

Join ACS for our Annual Supreme Court Preview, part of our observation of this year’s Constitution Day. After the seismic decisions handed down last Term, all eyes will be on the Court this fall to see what may come next. The Preview will feature a diverse group of constitutional and legal experts offering their insights into the upcoming Supreme Court Term that begins on October 3rd.

Welcome Remarks

Russ Feingold, ACS President

Speakers

Adam Liptak, Supreme Court Correspondent, The New York Times (moderator)

Deborah Archer, President, ACLU; Professor of Clinical Law and Co-Faculty Director of the Center on Race, Inequality, and the Law, NYU School of Law

Jonathan Diaz, Senior Legal Counsel, Campaign Legal Center

Kent Greenfield, Professor and Dean’s Distinguished Scholar, Boston College Law School

Wenona Singel, Associate Professor of Law and Director of the Indigenous Law & Policy Center, Michigan State University College of Law

Shoba Sivaprasad Wadhia, Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; Samuel Weiss Faculty Scholar; and Clinical Professor of Law, Penn State Law

Featuring amazing scholars — Neoshia Roemer, Heather Tanana, Lauren Van Schilfgaarde, and Dean Elizabeth Kronk Warner.

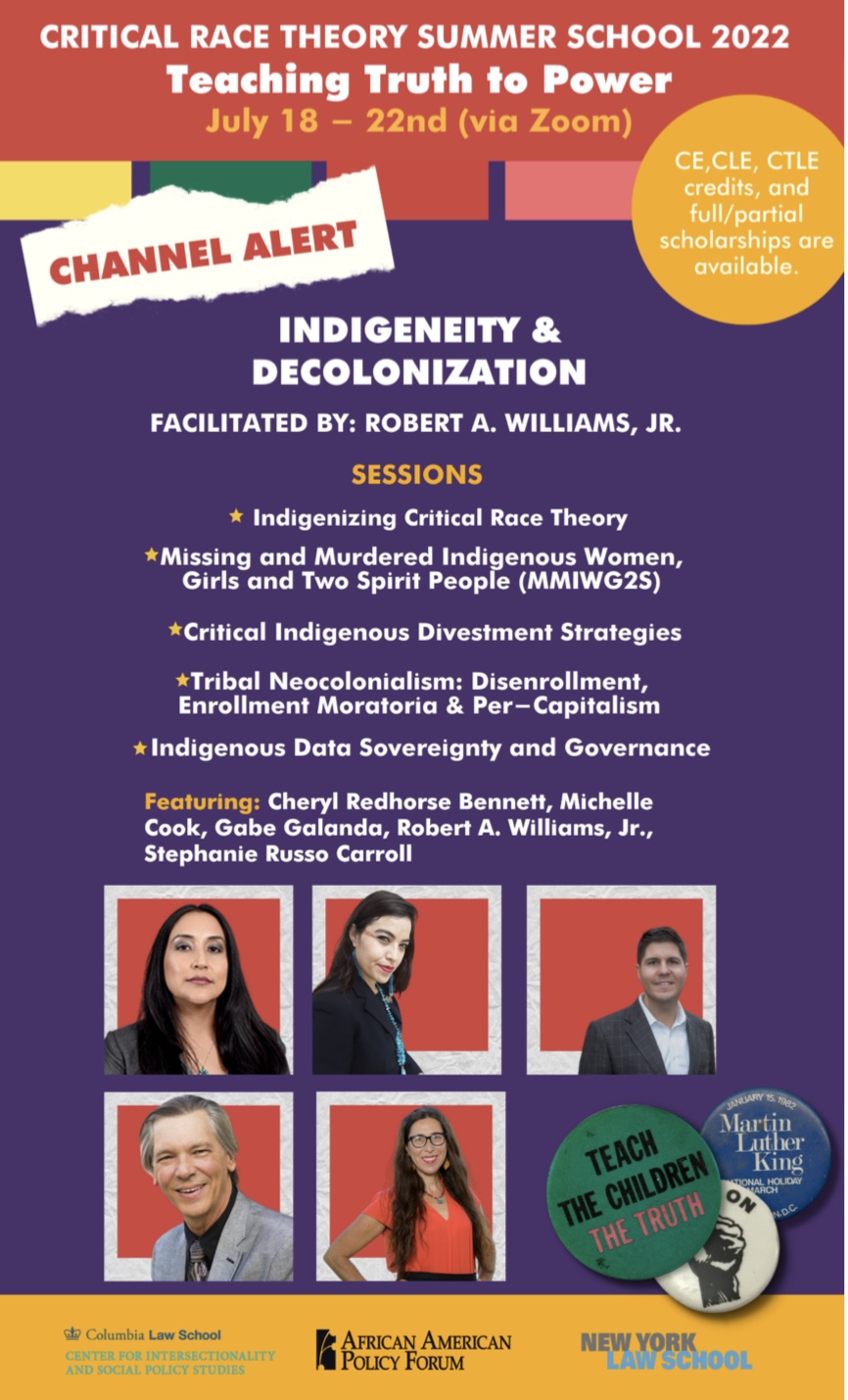

Kim Crenshaw’s African American Policy Forum is hosting it’s third Critical Race Theory Summer School and this year for the first time will have a full week of classes focused on indigenous peoples’ issues and the intersections with Critical Race Theory and Practice.

Michalyn Steele, Wenona Singel, Trevor Reed, and Angela Riley

Here:

Mohegan Women, the Mohegan Church, and the Lasting of the Mohegan Nation

Bethany R. Berger and Chloe Scherpa

An Uncomfortable Truth: Law as a Weapon of Oppression of the Indigenous Peoples of Southern New England

James D. Diamond

Uncomfortable Truths About Sovereignty and Wealth

Matthew L.M. Fletcher

Returning Home and Restoring Trust: A Legal Framework for Federally Non- Recognized Tribal Nations to Acquire Ancestral Lands in Fee Simple

Taino J. Palermo

The Continued Impact of Carcieri on the Restoration of Tribal Homelands: In New England and Beyond

Bethany Sullivan and Jennifer Turner

Colonial Legislation Affecting Indigenous Peoples of Southern New England as Organized by State

James D. Diamond

Resisting Indigenous Erasure in Rhode Island: The Need for Compulsory Native American History in Rhode Island Schools

Whitney Saunders

Here.

Matthew L.M. Fletcher

The goal of this Essay for the Wisconsin Law Review’s Symposium on the Restatement of the Law of American Indians is to develop a framework on the durability of this Restatement. The aadizookaanag are unusually durable in terms of their transmission of underlying, foundational lessons, but the stories change all the time. The earth diver story explores and describes the critically important connection between the Anishinaabeg and the creatures of Anishinaabewaki, but only at a very broad level of generality. How the Anishinaabe tribal government in the twenty-first century translates those principles into modern decision- making requires new analysis, new stories. Additionally, old aadizookaanag may fade into irrelevance, even disrepute, as times and conditions change.

Law is the same. Restatements are intended to be durable and persuasive, supported by the great weight of authority, but not permanent. There are provisions in the Indian law Restatement I believe are truly timeless, while the law restated in some sections is likely to change a great deal over the next few decades. I choose four sections in the Restatement and match each with one of the four directions sacred to the Anishinaabeg. The youngest direction, Waabanong, the east, is the most likely to change. The next youngest, Zhaawanong, the south, is older, but still subject to change. Niingaabii’anong, the west, is still older, wiser, less likely to change, but also very dark in its philosophies. Kiiwedinong, the north, is the oldest, wisest, and most durable, yet distant. A Restatement section includes blackletter law, law that is well-settled and indisputable. The reporters’ notes that accompany the blackletter law constitute the legal support for that statement of law. The stronger the legal support, the more durable the black letter.

In the east, I choose one of the plainest, easiest-to-restate principles of federal Indian law, the bar on tribal criminal jurisdiction over non- Indians. In the south, I choose the law interpreting the federal waivers of immunity allowing tribes to sue the United States for money damages. In the west, I choose the darkest, yet perhaps the most foundational, principles, the plenary authority of Congress in Indian affairs. For the north, I choose tribal powers, the oldest and most durable of all of the principles in the Restatement.

Diane P. Wood

Almost 200 years ago, in the Cherokee Nation cases, Chief Justice John Marshall famously described Indian tribes as “domestic dependent nations.” It’s a catchy phrase, but it falls far short of a clear description of the complex relationship between the Indian tribes, bands, nations, and similar groups in the territory encompassed by the United States and the government of that territory. It also elides the equally complex issue of the relationship between Indian tribes and the constituent states of the United States. In the end, the problem may be that modern notions of self- determination, integrity of national boundaries, and conquest simply do not map well onto the history of our part of the North American continent from the late fifteenth century to the present. The best we can do is to articulate rules, canons of interpretation, and principles from the law that has developed in the hope of clarifying and settling the law we now have.

No one could have undertaken that task with more sensitivity, expertise, and objectivity than the Reporters of the American Law Institute’s soon-to-be-published Restatement of the Law of American Indians—Professors Matthew L.M. Fletcher and Wenona T. Singel and Attorney Kaighn Smith, Jr. Indeed, this may have been one of the most challenging Restatements the ALI has ever undertaken. Most of the time, the common law (or interstitial law relating to a statute) has developed organically in the state and federal courts, and the job of the Reporters is to distill the rules that have emerged. This isn’t always easy, of course: sometimes no single rule floats to the top of the barrel, and so the Reporters must choose the one that seems best to represent the state of the law. Sometimes (though less often) the Reporters propose that the ALI adopt a minority position that is better reasoned or that seems to capture a trend of thinking.

Brian L. Pierson

Effective April 21, 2016, the Department of the Interior adopted new right-of-way regulations at 25 C.F.R. Part 169 that fundamentally change the Department’s historical approach. While the Right of Way Act still requires that the BIA approve rights-of-way, the new rules reflect a reinterpretation of the federal government’s trust responsibility with respect to rights-of-way. Instead of the federal government continuing to retain virtually all regulatory authority and substituting its judgment for that of tribes, the rules explicitly support tribal decision-making and the exercise of tribal regulatory authority.

This Essay briefly reviews the history of rights-of-way through Indian country, describes the new paradigm adopted under the 2016 regulations, and suggests how tribes can harness that paradigm to strengthen tribal sovereignty and generate revenue.

Lorenzo E. Gudino

You must be logged in to post a comment.