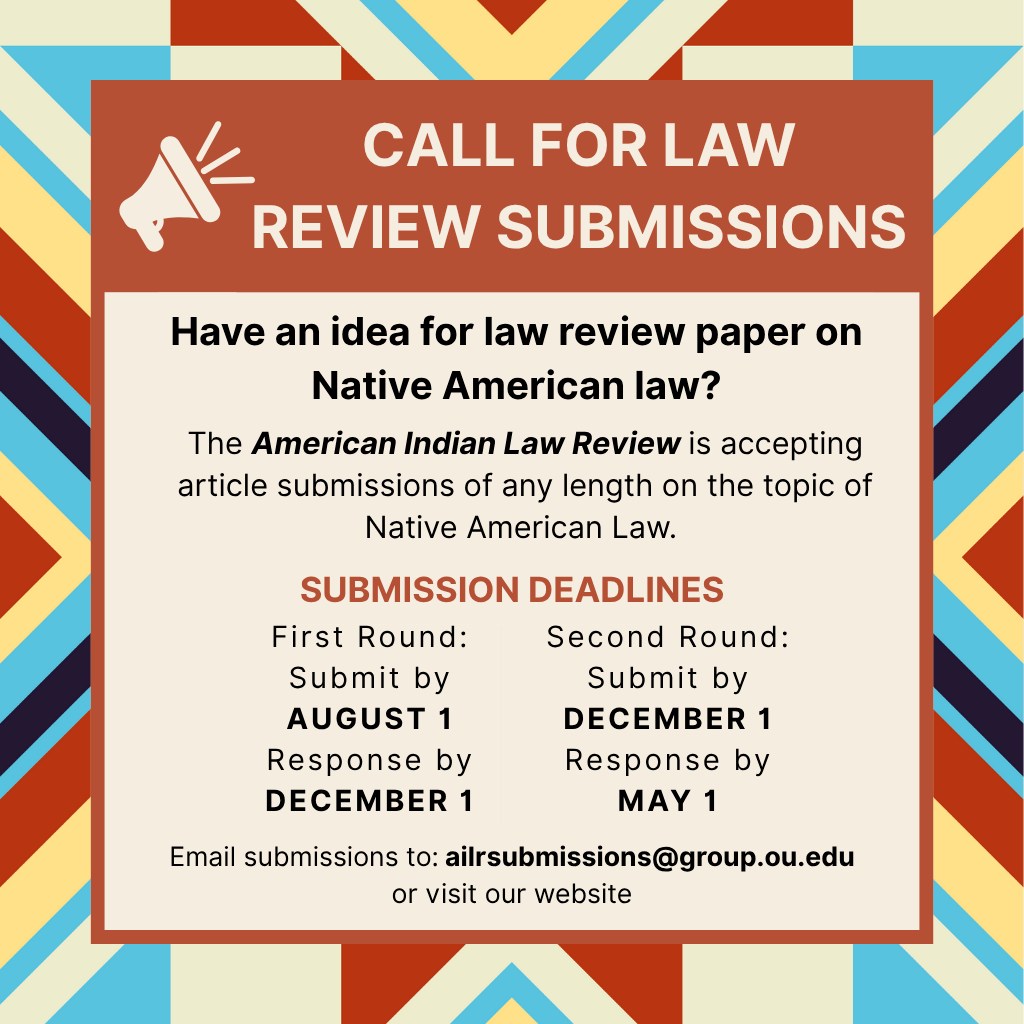

TOPICS: Papers will be accepted on any legal issue specifically concerning American Indians or other Indigenous peoples.

ELIGIBILITY: The competition is open to students enrolled in J.D. or graduate law programs at accredited law schools in the United States and Canada as of the competition deadline of Monday, February 28th, 2022. Editors of the American Indian Law Review are not eligible to compete.

AWARDS: The first place winner receives $1,500 and publication by the American Indian Law Review, an official periodical of the University of Oklahoma College of Law with international readership. The second place winner receives $750, and third place receives $400. Each of the three winning authors will also be awarded an eBook copy of Cohen’s Handbook of Federal Indian Law, provided by LexisNexis.

DEADLINE: All emailed entries must be received no later than 6 p.m. Eastern Standard Time on Monday, February 28th, 2022 (5 p.m. Central Standard Time). Entries will be acknowledged upon receipt. Submissions may be emailed to the American Indian Law Review at mwaters@ou.edu

JUDGES: Papers will be judged by members of the legal profession with an interest in American Indian law and by the editors of the American Indian Law Review.

STANDARDS: Papers will be judged on the basis of originality and timeliness of topic, knowledge and use of applicable legal principles, proper and articulate analysis of the issues, use of authorities and extent of research, logic and reasoning in analysis, ingenuity and ability to argue by analogy, clarity and organization, correctness of format and citations, grammar and writing style, and strength and logic of conclusions. All entries will be checked for plagiarism via an online service.

FORM: Entries must be a minimum of 20 double-spaced pages in length and a maximum of 50 double-spaced pages in length excluding footnotes or endnotes. All citations should conform to The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (21st ed.). The body of the email must contain the author’s name, school, expected year of graduation, current address, permanent address, and email address. No identifying marks (name, school, etc.) should appear on the paper itself. All entries must have only one author. Entries must be unpublished, not currently submitted for publication elsewhere, and not currently entered in other writing competitions. Papers entered in the American Indian Law Review writing competition may not be submitted for consideration to any other publication until such time as winning entrants are announced, unless the entrant has withdrawn the entry or received a notification of release prior to that time. Any entries not fully in accord with required form will be ineligible for consideration.

SUBMISSION: Submissions may be emailed to the American Indian Law Review at mwaters@ou.edu by the competition deadline. Entries may be sent as Microsoft Word, PDF, or WordPerfect documents.

CONTACT: E-mail — Michael Waters, mwaters@ou.edu

Phone Numbers — (405) 325-2840 and (405) 325-5191

This rules sheet is also available on the AILR website, at http://www.ailr.net/writecomp.

You must be logged in to post a comment.