Christian McMillen has published “I Didn’t Know That a Patent Was a Dangerous Thing”: Forced Fee Patents, Native Resistance, and Consent” in the Western Historical Quarterly.

Here is the abstract:

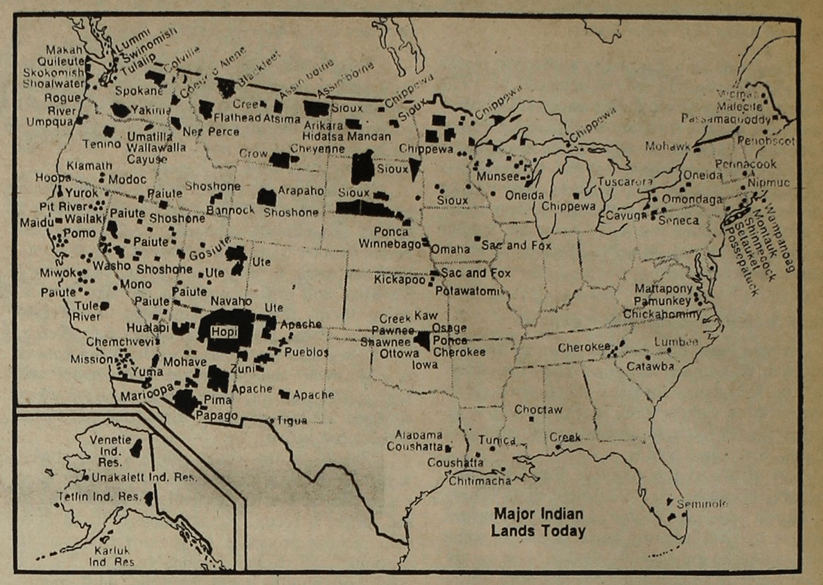

Between 1906 and 1920 the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) issued more than 32,000 fee patents, covering 4.2 million acres of land. More than half of the patents were issued between 1917 and 1920. The BIA forced many of these patents upon Native people without their consent. When individually allotted land went from trust to fee, the land was taxed and could be sold. The consequences were devastating. Was this legal? Many Native people protested their fee patents, but others did not. Indeed, protesting dispossession was an act of courage and defiance. Native protest led to a legal precedent that had an impact across Indian country: consent was required. But was compliance synonymous with consent? Must one resist a policy found to be illegal in order for it not to apply? For a time, the answer was yes. Ideas about consent began to change leading to another series of legal challenges to the Bureau’s forced fee patent policy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.