Here is “Counterpoint: Tribal rights, futures must not be plundered again” in the Minnesapolis Star-Tribune.

Here is “Counterpoint: Tribal rights, futures must not be plundered again” in the Minnesapolis Star-Tribune.

Over the past few weeks, a number of states have been considering state ICWA laws. I’m keeping the bills updated here, along with their current status when I’m notified of it. https://turtletalk.blog/icwa/comprehensive-state-icwa-laws/

Today the AP had news coverage of the bills here

Finally, here is a link to the testimony that took place yesterday in the Minnesota Senate.

This bill is supported by the ICWA Law Center, one of the only organizations that provides direct, trial level legal services to Native families, and they do it very well. They are currently holding a fundraiser with Heart Berry:

And listen, I’m not responsible if you follow that link and then get sucked into buying a whole bunch of stuff from Heart Berry because it’s basically impossible not to. I don’t make the rules.

I won’t lie, guys, I had to read this one multiple times to figure out what was going on. Essentially the Montana legislature passed a law without understanding the difference between hearings that fall under 1912(a) and 1922. 1912 governs foster care proceedings and requires notice, active efforts, qualified expert witness testimony, etc. 1922 governs emergency proceedings (1922 has language that all states essentially read out of the statute to achieve this jurisdiction, which only makes sense to ICWA practitioners and no one else). Emergency proceedings do not require notice and the other 1912 protections, but it has a higher standard for removal (imminent physical damage or harm). The Montana statute denied parents of Indian children a faster emergency hearing because of the belief that 1912 standards (specifically notice) had to be hit before there could be a reason. The Court overturned this language.

Also interesting is the issue of trying to appeal proceedings that are emergency/shelter care/24 hour/48 hour/preliminary hearings in child protection proceedings. There’s often not a final order coming out of those hearings, and no way for a parent or tribe to appeal an emergency decision (this was an issue in the In re Z.J.G. case in Washington as well). Here, the District Court argued there was no way for the appellate court to hear the case because of the nature of the hearings.

Finally, the District Court argues this matter does not meet the threshold criteria for a writ of supervisory control because no urgent or emergency factors make appeal an inadequate remedy. The court alleges that in this case, it was later determined that O.F. is not an Indian child, and A.J.B. and O.F. have been “conditionally reunited.” However, as A.J.B. asserts in her petition, she does not appear to have any remedy on appeal for the denial of her right to an EPS [emergency] hearing, and the potentially erroneous loss of the right to parent, even for a short time, is a matter of great urgency.

Here the appellate Court heard the case anyway and overturned the statute.

Of course, you may also remember the federal case in South Dakota attempting to remedy emergency hearing practices there in ICWA cases that was dismissed on appeal because the federal court stated there were Younger abstention issues.

Forthcoming in the Juvenile & Family Court Journal

From 2017 through 2022, while the Indian Child Welfare Act (“ICWA”) was under direct constitutional attack from Texas, state courts around the country continued hearing appeals on ICWA with virtually no regard for the decision making happening in Haaland v. Brackeen in the federal courts. For practitioners following or working on both sets of cases, this duality felt surreal, as they practiced their daily work under an existential threat. The data in this article draws from the authors’ previous publications providing annual updates on ICWA appeals, and now includes cases through 2021. It provides a description of appellate data trends across this time period, as well as for each year, while also highlighting key appellate decisions from jurisdictions across the country. Perhaps what this article demonstrates more than any single thing is the amount that ICWA is a part of child welfare practitioners’ daily lives now, in a way that will be difficult to upend, regardless of the Supreme Court’s ultimate decision.

This is particularly recommended for practitioners–we’ve taken the data from all our past articles to put them into one. One of our charts still needs a labels fix from our data expert, Alicia Summers, but otherwise the article has undergone peer review and will be published soon.

The Court agreed that ICWA applied to a third party custody petition where the parent could not get her child back upon demand, but rejected the argument the child must be returned immediately under 1920.

These type of third party cases are particularly important to keep an eye on, as agencies often push cases in this direction to avoid filing a petition on a parent (this itself is a complicated topic). Regardless, parents and tribes shouldn’t lose certain rights under ICWA if the placement meets the definition of a foster care placement under the law.

Neoshia Roemer has posted “Un-Erasing American Indians and the Indian Child Welfare Act from Family Law,” forthcoming in the Family Law Quarterly, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

In 1978, Congress enacted the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) as a remedial measure to correct centuries-old policies that removed Indian children from their families and tribal communities at alarming rates. Since 1978, courts presiding over child custody matters around the country have applied ICWA. Over the last few decades, state legislatures, along with tribal community partners and advocates, have drafted and enacted state ICWA laws that bolster the federal ICWA laws. Despite four decades of ICWA, trends in child welfare demonstrate that Indian children are still vastly overrepresented in the child welfare system. Because tribal communities, advocates, community partnerships, and scholars work tirelessly to both ensure and improve ICWA compliance, ICWA still provides some of the best outcomes for Indian children through both family reunification and/or placement within their tribal communities.

However, family law often minimizes or mischaracterizes what the Act does. While ICWA is a complex law and even an entire semester may not fully provide justice to the breadth of the Act, this characterization of ICWA creates a stigma around the law. Family law scholars and practitioners can no longer overlook ICWA in conversations and teachings. Stigmatizing ICWA in the classroom contributes to the erasure of American Indians from our society at large and from our classrooms. This allows legitimized racism against this community to seep into both the classroom and the practice area.

Accordingly, this article discusses how family law classrooms can incorporate ICWA into conversations on family law as a step in eliminating bias in the legal academy and in the profession against American Indians. This article describes some of the history around ICWA, how family law feeds into the erasure of American Indians in the legal field, some misconceptions about ICWA, and how we can tie ICWA and other issues impacting American Indians into our classroom teachings on family law.

This was Part II, Part I was here.

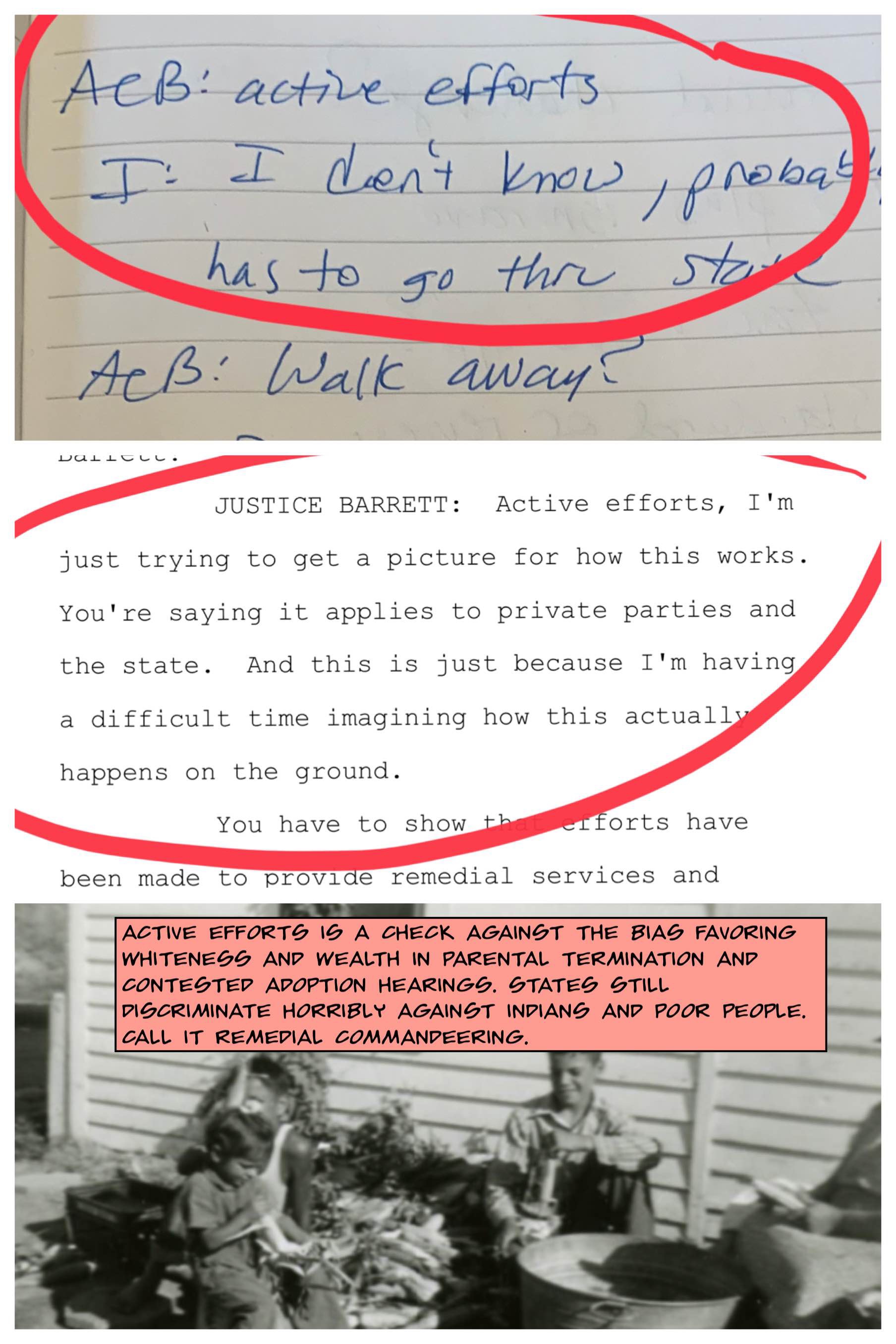

Fletcher and Randall F. Khalil have published “Preemption, Commandeering, and the Indian Child Welfare Act” in the Wisconsin Law Review.

Blurb:

We argue that the anti-commandeering challenges against ICWA are unfounded because all provisions of ICWA provide a set of legal standards to be applied in states which validly and expressly preempt state law without unlawfully commandeering the states’ executive or legislative branches. Congress’s power to compel state courts to apply federal law is long established and beyond question.

Here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.