Brackeen v. Haaland

Brackeen/ICWA CLE from Fort

Since we all now have to deal with it, might as well deal with it together:

Haaland v. Brackeen [ICWA] Cert Stage Briefing Completed

All the briefs are here. The Court will first consider the case at this Friday’s conference (1/7).

Washington Monthly: “Indian Tribes Are Governing Well. It’s the States That Are Failing”

Under Fletcher’s byline, here.

Native America Calling: Monday, September 20, 2021 – ICWA: Federal protections for children under constant legal pressure

Here.

Four Cert Petitions Filed in Texas v. Haaland [Brackeen ICWA Case]

Today Texas, the individual plaintiffs, the Solicitor General, and the intervening tribal nations filed petitions for certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court asking the Court to review the Fifth Circuit decision regarding the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act. There will be some additional briefing over the next 30 days, and then/eventually the Court will decide whether to hear the case or not.

The Indian Law Clinic at MSU Law represents the intervening tribes in this case.

Season 2 of This Land Podcast Debuts August 23

This season is all about the Indian Child Welfare Act and the federal attacks on it.

ALM – as referred to in court documents – is a Navajo and Cherokee toddler. When he was a baby, a white couple from the suburbs of Dallas wanted to adopt him, but a federal law said they couldn’t. So they sued. Today, the lawsuit doesn’t just impact the future of one child, or even the future of one law. It threatens the entire legal structure defending Native American rights.

In season 2 of This Land, host Rebecca Nagle investigates how the far right is using Native children to quietly dismantle American Indian tribes.

Tune in beginning August 23rd.

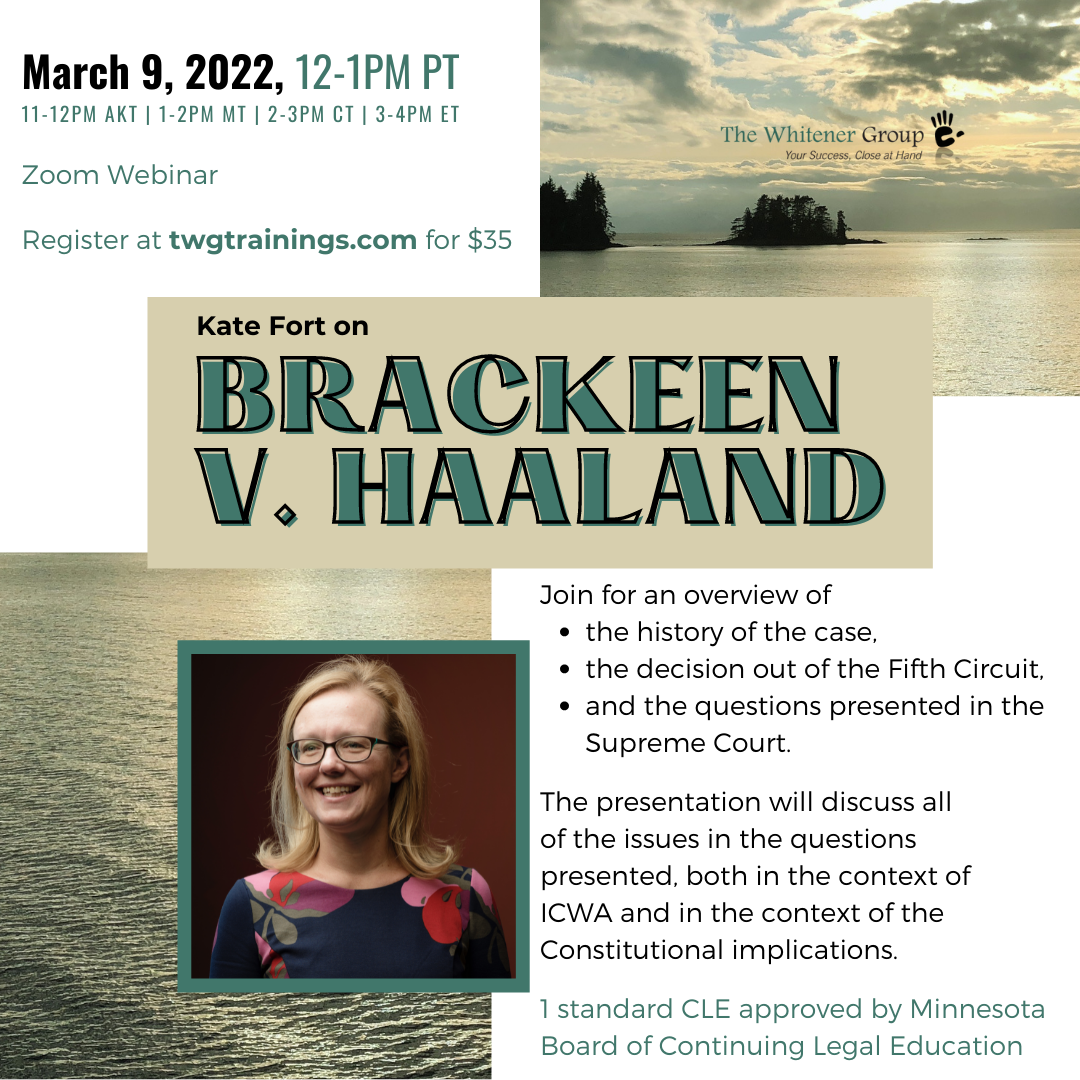

Brackeen 1 Hour CLE Next Week

Registration Link: https://www.twgtrainings.com/brackeen-decision

Does Brackeen v. Haaland Apply:

This document is primarily for non-lawyers, so while you can @ me about details, there is a reason this document doesn’t get into the nitty gritty question of federal court jurisdiction in state court trials (please note the work the word “may” is doing). We hope this will be helpful for tribal social workers, their state counterparts, reporters, and maybe some lawyers who are trying to understand the implications of a 325 page decision.

Brackeen Decision Summary

Based on my inbox, my ims, and my texts, the best thing I can do this morning is a post on the decision. A few caveats–I will not speculate about what happens next because I don’t know what’s going to happen next and it’s frankly not helpful. This is my own understanding of a ridiculously complicated opinion less than 24 hours after it was released and no one else’s, but I am indebted to a number of practitioners last night who emailed and texted as we worked our way through it. They know who they are.

Judge Dennis and Judge Duncan each wrote about 150 pages, clearly hoping one or the other would gain the majority. Then five additional judges (Owen, Wiener, Haynes, Higginson, Costa) wrote concurrences and dissents and/or both. The first five pages of the document are a per curiam description of where everyone ended up. These five pages are probably the most helpful part of the decision. What makes this decision particularly confounding is that due to the make up of the court, there was an opportunity for an evenly split bench, which is what happened a lot. And as Indian law practitioners know all too well, a split bench doesn’t make for a precedential decision (and are supposed to be super short, but no such luck here).

Application

I think the best place to start is the question I’ve been asked the most–where does this apply? How will this affect my on-going case? First, the mandate issue date on the opinion is not until June 1 (this is in PACER). Therefore, if nothing happens at all (remember, I’m not future speculating), then none of this applies till June 1. Second, I believe the parts of the decision that the majority agrees on is applicable only in the Fifth Circuit. Much like no one in California or Michigan much cares about the Neilson v. Ketchum decision in the Tenth Circuit, there’s no real reason for a vast majority of state courts to wrestle with this case.

The evenly split parts? I like to think of them as an unpublished advisory opinion. Take a look at footnote one to address those parts. The Court uses the term “affirmed without precedential opinion” which does not appear in any Westlaw search I’ve done so far. However, as I pointed out last night, Judge Costa’s concurrence and dissent (which appears at the very end of the document) points out pretty clearly that the federal court decision is not binding on a state court. He then addresses the way in which this decision cannot provide redressability. The language in his first paragraph on page 307 may prove to be the most helpful those who wrote me about on-going cases. I’m going to put it in here because I appreciate his writing:

It will no doubt shock the reader who has slogged through today’s lengthy opinions that, at least when it comes to the far-reaching claims challenging the Indian Child Welfare Act’s preferences for tribe members, this case will not have binding effect in a single adoption. That’s right, whether our court upholds the law in its entirety or says that the whole thing exceeds congressional power, no state family court is required to follow what we say.

2 from Judge Costa’s decision, 307 in the PDF

ICWA is Constitutional

If you’ve made it this far, let’s start with the good news–these are things the majority agreed on:

[T]he en banc court holds that Congress was authorized to enact ICWA. We conclude that this authority derives from Congress’s enduring obligations to Indian tribes and its plenary authority to discharge this duty.

***

In addition, for the en banc court, we hold that ICWA’s “Indian Child” designation and the portions of the Final Rule that implement it do not offend equal protection principles because they are based on a political classification and are rationally related to the fulfillment of Congress’s unique obligation toward Indians.

***

We also hold for the en banc court that § 1915(c) does not contravene the nondelegation doctrine because the provision is either a valid prospective incorporation by Congress of another sovereign’s law or a delegation of regulatory authority.

***

Further, we hold for the en banc court that the BIA acted within its statutory authority in issuing binding regulations, and we hold for the en banc court that the agency did not violate the APA when it changed its position on the scope of its authority because the agency provided a reasonable explanation for its new stance.

152 from Judge Dennis’s opinion, 159 in the PDF

Judge Dennis would have held for the Defendants and completely reversed the district court on all issues except standing, had he garnered a majority of the court.

In addition, here are the specific ICWA provisions challenged and either found constitutional by the majority:

1911(c)

1912(b)

1912(c)

1912(e), (f) (except for QEW)

1913(a)-(d)

1914

1915(c)

1916(a)

1917

or could not garner a majority and are therefore not precedential:

1915 (a)-(b)

1912 (a)

1951 (a)

Provisions of ICWA and the Regs that May Not Apply in the Fifth Circuit

Judge Duncan’s opinion essentially stands for the exact opposite conclusions, but he did not get a majority. He only got a majority on three issues. The majority agreed the following in ICWA are unconstitutional as applied to states under the commandeering doctrine in the Fifth Circuit:

25 U.S.C. 1912(d) (Active efforts provision) (Judge Duncan’s decision, IIII(B)(1)(a)(i))

25 U.S.C. 1912(e), (f) as it applies to the qualified expert witness provision (Judge Duncan’s decision, III(B)(1)(a)(ii))

25 U.S.C. 1915(e) (recordkeeping regarding placements) (Judge Duncan’s decision, III(B)(1)(a)(iv))

In addition, the parts of the Final Rule that implement those provisions are also no longer applicable, though I would draw people’s attention to 25 C.F.R. 23.144 which addresses severabillity. I believe there is an argument to be made that these provisions are only knocked out as to the states in the Fifth Circuit, not to private parties. The Court did not identify the specific rules that implement 1912(d)-(f) and 1915(e), so here is my best guess on which ones may not longer apply in the Fifth Circuit:

25 C.F.R. 23.2 (active efforts definition)

25 C.F.R. 23.120 (active efforts)

25 C.F.R. 23.121 (but only the parts that reference qualified expert witness)

25 C.F.R. 23.122 (qualified expert witness)

The Court did specifically reject by majority the following provisions of the Final Rule:

25 C.F.R. 23.132 (b) (that good cause to deviate from the placement preferences requires a clear and convincing evidence standard/finding)

25 C.F.R. 23.141 (specifically identified as rejected/record keeping)

I apologize for not stating something that I should have said at the start:

This decision has no effect on state ICWA laws, since it is based on commandeering (the feds making the states do something, not the state choosing to do something) or the APA (again, if a state wants to maintain records, it can, and state laws or court decisions that enforce a C&C burden for good cause based on ICWA itself or state law should be fine as well.).

Trust me when I say, there are a LOT of words in this decision (I had to briefly walk away when I hit footnote 2, an extraordinarily long, multipage footnote on Madison and the Federalist papers), but a lot of the words are just that. There’s very little legal substance here. I think it’s revealing to read the attempt at remedy in Judge Duncan’s opinion–as had been argued repeatedly, nothing this court decided would redress the harms claimed by the plaintiffs.

Students at the MSU Indian Law Clinic will be working on additional materials, such as breaking down the decision by judge if possible, and developing a chart (as are a number of other groups). Ours will be directed for the audience of in-house ICWA counsel. I hope this is helpful.

You must be logged in to post a comment.