Torey Dolan has posted “American Indian Geopolitical Rights” on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

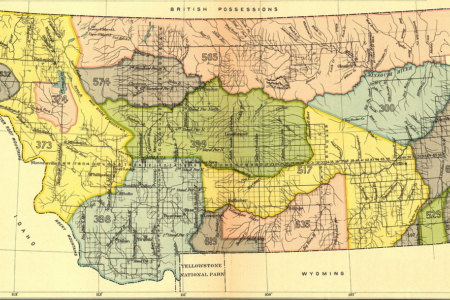

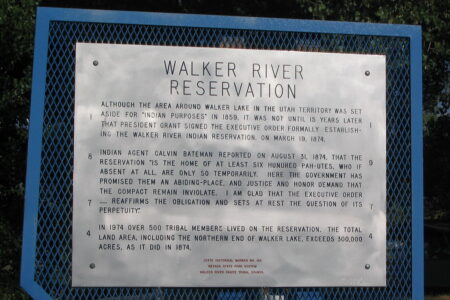

American Indian people hold a unique legal position under the United States Constitution and within American law based on Indian status. This unique relationship at times reflects the cultural, spiritual, and legal ties to land that are unique to American Indians and represent aberrations in American law. This fundamentally impacts the lives and interests of American Indians, including in matters of representational democracy. This paper seeks to contextualize the proscriptive legal ties that American Indians have with land under law, termed herein “Indian Geopolitical Rights.” This paper argues that American Indian Geopolitical Rights reflect not only significant cultural interests of American Indians, but that American Indians have substantive rights that are tied to place that impacts how Indians engage with democratic systems and conceive of political representation. As such, the needs of American Indians necessitate a consideration of Indian geopolitical rights in the development, maintenance, and implementation of local, state, and federal electoral systems. This paper argues that Indian geopolitical rights are incumbent upon states, that election law doctrine is currently ill-equipped to protect Indian geopolitical rights, and incorporating Indian geopolitical rights is consistent with the U.S. Constitution and its principles of federalism.

Recommended!

You must be logged in to post a comment.