Jason Robison has published “Relational River: Arizona v. Navajo Nation & the Colorado” in the UCLA Law Review.

Here is the abstract:

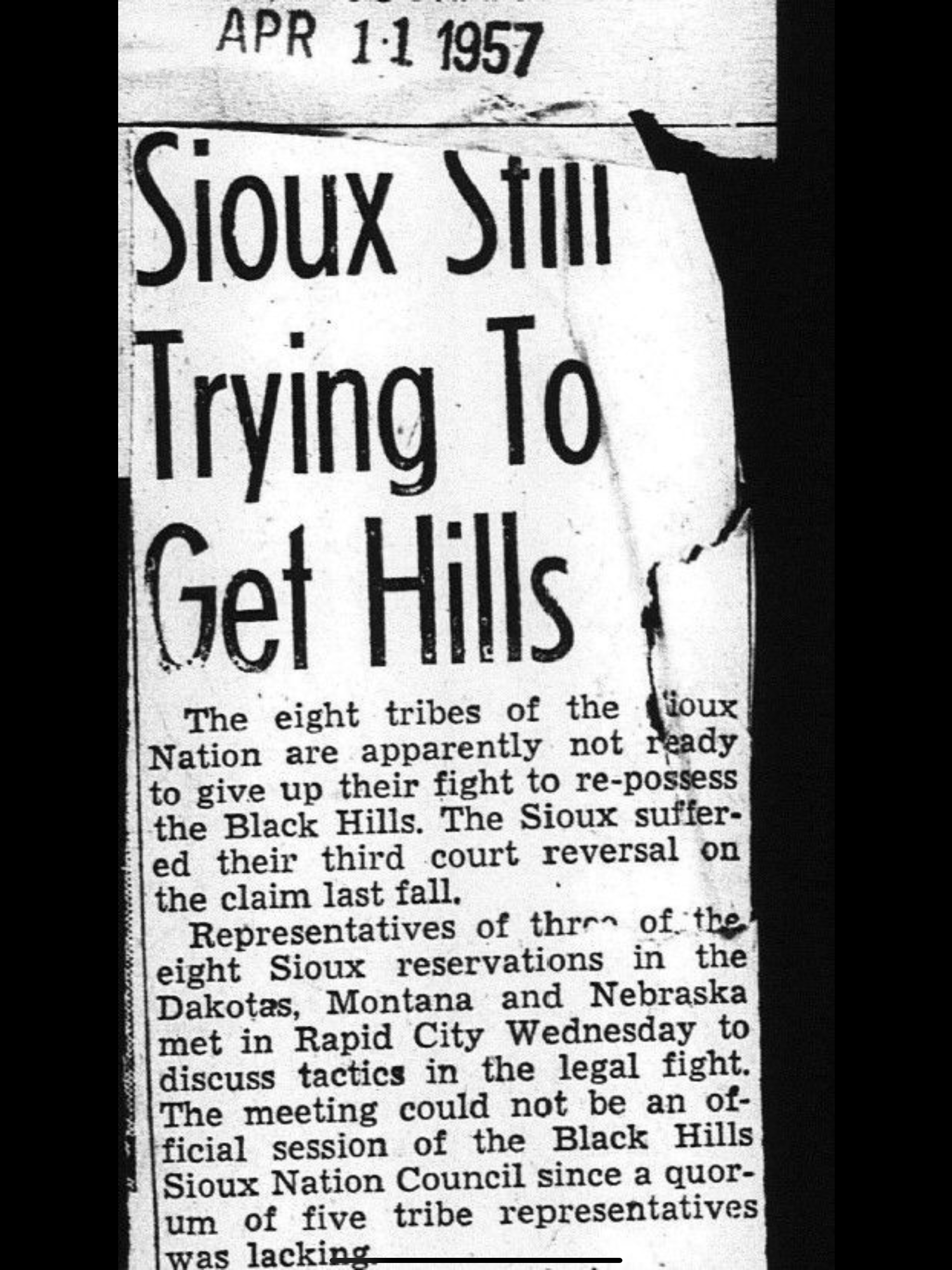

It is not every day the U.S. Supreme Court adjudicates a case about the water needs and rights of one of the Colorado River Basin’s thirty tribal nations and the trust relationship shared by that sovereign with the United States. Yet just that happened in Arizona v. Navajo Nation in June 2023. As explored in this Article, the Colorado is a relational river relied upon by roughly forty million people, reeling from climate change for nearly a quarter century, and subject to management rules expiring and requiring extensive, politically charged renegotiation by 2027. Along this relational river, Arizona v. Navajo Nation was a milestone, illuminating water colonialism and environmental injustice on the country’s largest Native American reservation, and posing pressing questions about what exactly the trust relationship entails vis-à-vis the essence of life. Placing Arizona v. Navajo Nation in historical context, the Article synthesizes the case with an eye toward the future. Moving forward along the relational river, the trust relationship should be understood and honored for what it is, a sovereign trust, and fulfilled within the policy sphere through a host of measures tied, directly and indirectly, to the post-2026 management rules. Further, if judicial enforcement of the trust relationship is necessary, tribal sovereigns in the basin (and elsewhere) should not view the Court’s 5–4 decision as the death knell for water-related breach of trust claims, but rather as a guide for bringing cognizable future claims and reorienting breach of trust analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.