Here is the opinion in Ito v. Copper River Native Association:

[14]We consider the Washington Supreme Court’s reasoning to be persuasive and note that other states also consider a specific, recent claim of Native heritage to be a “reason to know” the child is an Indian child.47 Tribes have many methods to determine membership or eligibility for membership, including lineal descent or blood quantum.48Additionally, a tribe may enroll an eligible child after being notified by a state agency that the child is involved in a child custody proceeding.49 Because the tribe as sovereign has exclusive power to determine tribal membership or eligibility for tribal membership, notifying the tribe when a child who may be a member is involved in a child custody proceeding is imperative to implementing ICWA’s protections of tribes and tribal members.

***

Perhaps more importantly, treating a parent’s uncertain statements as determinative in a context like this could undermine tribal sovereignty, because the tribe decides who is a member.56 It is a “basic federal rule” that tribes are the exclusive authority on their membership.57 We have previously held that absent a determination by a tribe, a child’s membership or eligibility for membership in a tribe is likely not subject to judicial admission, recognizing the legal authority of tribes to determine membership.58 Giving too much weight to the statements of a party without proof or input from the tribe would undermine this fundamental principle.

***

We reiterate that a “reason to know” that children are Indian children may arise in many different ways, based upon a multitude of different pieces of information, and determining whether there is a “reason to know” is a fact-intensive analysis requiring consideration of the record of information and context presented in any given case.64 Here, Jimmy’s specific claim that he is a recent descendant of a CIRI shareholder, paired with his early assertions related to his children’s tribal affiliation, gave OCS and the court “reason to know” his children are Indian children, triggering OCS’s duty to inquire and to treat the children as Indian children pending a definitive answer as to their status.

Here is the decision. sp7628

The facts of this case were a little unusual, where a foster family attempted to have a child in their care made a member of one tribe when he was already a citizen of another. The holdings, however, are useful both for clarity in the regulations for the determination of an Indian child’s tribe, and for keeping state courts out of tribal citizenship decisions.

Court decisions reflect the same rule of deference to the tribe’s exercise of control over its own membership. The U.S. Supreme Court has long recognized tribes’ “inherent power to determine tribal membership.” In John v. Baker we recognized that “the Supreme Court has articulated a core set of [tribes’] sovereign powers that remain intact [unless federal law provides otherwise]; in particular, internal functions involving tribal membership and domestic affairs lie within a tribe’s retained inherent sovereign powers.” We have also “long recognized that sovereign powers exist unless divested,” and “ ‘the principle that Indian tribes are sovereign, self-governing entities’ governs ‘all cases where essential tribal relations or rights of Indians are involved.’ ”

Chignik Lagoon’s argument would require state courts to independently interpret tribal constitutions and other sources of law and substitute their own judgment on questions of tribal membership. This argument is directly contrary to the directive of 25 C.F.R. § 23.108.

The Indian Law Clinic at MSU College of Law provided research and technical assistance to the Village of Wales in this case.

The question of qualified expert witness (QEW) has confounded the Alaska Court for years, and unfortunately the regulations and guidelines didn’t provide quite as much clarification as they needed. That said, this decision seems to chart a new course for the Alaska Supreme Court:

As explained further below, the superior court’s interpretation of Oliver N. was mistaken. An expert on tribal cultural practices need not testify about the causal connection between the parent’s conduct and serious damage to the child so long as there is testimony by an additional expert qualified to testify about the causal connection.

* * *

In both cases there is reason to believe cultural assumptions informed the evidence presented to some degree. Had the cultural experts had a chance to review the record — particularly the other expert testimony — they may have been able to respond to and contextualize it. For instance, Dr. Cranor emphasized attachment theory and the economic situation of the families in both cases — areas that may implicate cultural mores or biases. If the cultural experts were aware of this testimony, they could haven addressed attachment theory, economic interdependence, and housing practices in the context of prevailing tribal standards.

Here are the materials in Association of Village Council Presidents Regional Housing Authority v. Mael:

Here is the petition in Scudero v. Alaska:

Questions presented:

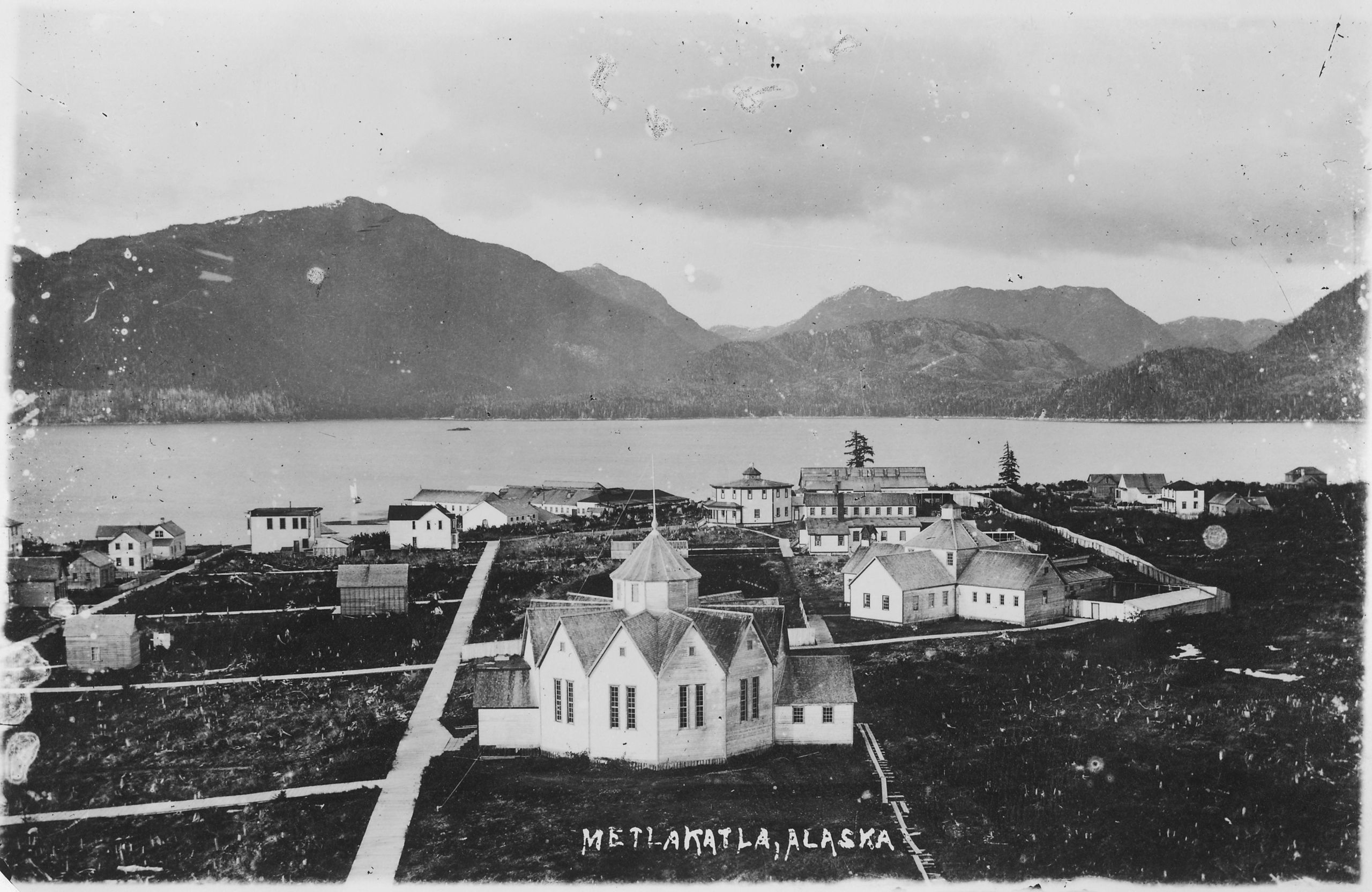

1. Can the State of Alaska by criminal prosecution and threat of fine and incarceration prohibit Alaska Native members of the Metlakatla Indian Community and Tribe and the Tsimshian Nation, who have vested broad off-reservation, aboriginal, treaty, presidential proclamation, and congressional legislature enacted, and granted, fishing rights, from harvesting fish in their traditional Pacific Ocean fishing waters, and Annette Islands Reserve related waters, which fishing is essential to their culture, heritage, and lifestyle, and vital to the very purpose for which the Reserve was established and dedicated, under the guise of “conservation necessity” by criminally banning those natives who are “un-permitted” i.e., do not have State of Alaska “limited entry permits,” which permits are bought and sold for many tens of thousands of dollars and well beyond the financial resources and means of most natives, and which permits were issued in a restricted and “qualifying fashion” that discriminates against those Metlakatla Natives?

2. Should this Court act as the United States Supreme Court did on two (2) prior occasions in Alaska Pacific Fisheries Company v. United States, 248 U.S. 78, 39 S.Ct.40, 63 L.Ed. 138 (1918) and Metlakatla Indian Community v. Egan, 369 U.S. 45, 82 S.Ct. 552, 7 L.Ed. 262 (1962), to protect the rights of the Tsimshian Nation members of the Metlakatla Indian Community and Tribe as to the Annette Islands Reserve, as to vested fishing rights relating to the Reserve, or allow the State of Alaska and the Alaska Supreme Court to abrogate and extinguish those aboriginal, treaty, presidential proclamation, and congressional legislation and grant rights [which abrogation involves native fishing rights that evolve from the Russian Treaty of Succession of 1867 (Alaska Acquisition Treaty) and subsequent federal legislation including the Alaska Statehood Act, (72 Stat. 339) Public Law 85-508, 85th Congress, H.R. 7999, July 7, 1958, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (“ANCSA,” 43 U.S.C. § 1601 et. seq.), and violation of the duties and obligations of the State of Alaska thereunder], with devastating impacts on the Metlakatlans and their thousands of years of culture tradition and heritage under the guise of the misapplied “conservation necessity principle,” where said misapplication is discriminatory against the Tsimshian Metlakatla Tribe and natives such as John Albert Scudero, Jr. and there will be no real impact on the Alaska limited entry fishing program or the fisheries of Alaska if the natives’ vested rights are honored?

3. Can the State of Alaska by such criminal prosecution abolish those Alaska Natives’ fishing rights when allowing the small number of Metlakatlans to exercise their rights will in reality have little impact on the State of Alaska Limited Entry Fisheries Program, or salmon fisheries; although such discriminatory ban and prohibition and criminal prosecution abrogates and emasculates those vested fishing rights and destroys the basic purpose for which the Reserve was established by presidential proclamation and congressional action, as a reserve for the Alaska Natives to enjoy and practice their historical and traditional fish harvesting lifestyle, as opposed to an agrarian lifestyle which was and is not possible on the Reserve; or does the State of Alaska have to honor those vested rights of the Alaska Natives, Metlakatlans, as the Courts have held as to vested native fishing rights and allow them to fish on equal footing and par with non-native fishers, merely perhaps equally subject to true conservation regulatory measures as to “manner and means,” and “seasons” of harvest and not subject to a criminal prosecution impressed discriminatory total ban on un-permitted natives so exercising their vested fishing rights?

Lower court materials here.

These kind of cases feel like they are coming in a rapid speed right now–this is the third one I am aware of that have been/will be decided this spring. The issue is the attempted interference by foster parents in a transfer to tribal court proceeding, usually by trying to achieve party status.

Having considered the parties’ briefing — and assuming without deciding both that J.P. and S.P. were granted intervenor-party status in the superior court and that such a grant of intervenor-party status would have been appropriate4 — we dismiss this appeal as moot. “If the party bringing the action would not be entitled to any relief even if it prevails, there is no ‘case or controversy’ for us to decide,” and the action is therefore moot.5 As explained in our order of July 9, 2021, even if we were to rule that the superior court erred in transferring jurisdiction, we lack the authority to order the court of the Sun’aq Tribe, a separate sovereign, to transfer jurisdiction of the child’s proceeding back to state court.6 And we lack authority to directly review the tribal court’s placement order.7

The Court cites my all time favorite transfer case–In re M.M. from 2007. Not only is that decision a complete endorsement of tribal jurisdiction, it also explains concurrent jurisdiction (especially useful when you are operating in a PL280 state), which is not the power to have simultaneous jurisdiction, but the power to chose between two jurisdictions.

When we speak of “concurrent jurisdiction,” we refer to a situation in which two (or perhaps more) different courts are authorized to exercise jurisdiction over the same subject matter, such that a litigant may choose to proceed in either forum.FN13 As the Minnesota Supreme Court explained in a case involving an Indian tribe, “[c]oncurrent jurisdiction describes a situation where two or more tribunals are authorized to hear and dispose of a matter *915 and the choice of which tribunal is up to the person bringing the matter to court.” (Gavle, supra, 555 N.W.2d at p. 290.) Contrary to Minor’s apparent belief, that two courts have concurrent jurisdiction does not mean that both courts may simultaneously entertain actions involving the very same subject matter and parties.

Here are the available materials in Scudero v. State:

Sometimes I read the first paragraph of a decision and just put my head on my desk. Feel free to join me today:

An Alaska Native teenage minor affiliated with the Native Village of Kotzebue (Tribe) was taken into custody by the Office of Children’s Services (OCS) and placed at a residential treatment facility in Utah. She requested a placement review hearing after being injured by a facility staff member. At the time of the hearing, the minor’s mother wanted to regain custody. At the hearing the superior court had to make removal findings under the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) as well as findings authorizing continued placement in a residential treatment facility under Alaska law. ICWA requires testimony from a qualified expert witness for the removal of an Indian child. At the hearing, the minor’s Utah therapist testified as a mental health professional. The minor, as well as her parents and the Tribe, objected to the witness being qualified as an ICWA expert, but the superior court allowed it. The minor argues that the superior court erred in determining that the witness was qualified as an expert for the purposes of ICWA. Because the superior court correctly determined that knowledge of the Indian child’s tribe was unnecessary in this situation when it relied on the expert’s testimony for its ICWA findings, we affirm.

You must be logged in to post a comment.