Here are the new materials in United States v. Abouselman (D.N.M.):

Prior post here.

Here are the new materials in United States v. Abouselman (D.N.M.):

Prior post here.

Alyssa Couchie has published “ReBraiding Frayed Sweetgrass for Niijaansinaanik: Understanding Canadian Indigenous Child Welfare Issues as International Atrocity Crimes” in the Michigan Journal of International Law.

Here is the abstract:

The unearthing of the remains of Indigenous children on the sites of former Indian Residential Schools (“IRS”) in Canada has focused greater attention on anti-Indigenous atrocity violence in the country. While such increased attention, combined with recent efforts at redressing associated harms, represents a step forward in terms of recognizing and addressing the harms caused to Indigenous peoples through the settler-colonial process in Canada, this note expresses concern that the dominant framings of anti-Indigenous atrocity violence remain myopically focused on an overly narrow subset of harms and forms of violence, especially those committed at IRSs. It does so by utilizing a process-based understanding of atrocity and genocide that helps draw connections between familiar, highly visible, and less recognized forms of atrocity violence, which tend to be overlapping and mutually reinforcing in terms of their destructive effects. This process-based understanding challenges the neocolonial, racist, and discriminatory attitudes reflected in the drafting and interpretation of the Genocide Convention and other atrocity laws that ignore the lived experiences of subjugated groups. Utilizing this approach, this note argues that, as applied to Indigenous populations, Canada’s longstanding discriminatory child welfare practices and policies represent an overlooked process of anti-Indigenous atrocity violence. Only by understanding current child welfare challenges facing Indigenous communities as interwoven with longstanding anti-Indigenous atrocity processes, such as the IRS system, can we understand what is at stake for affected communities and fashion appropriate remedies in international and domestic law.

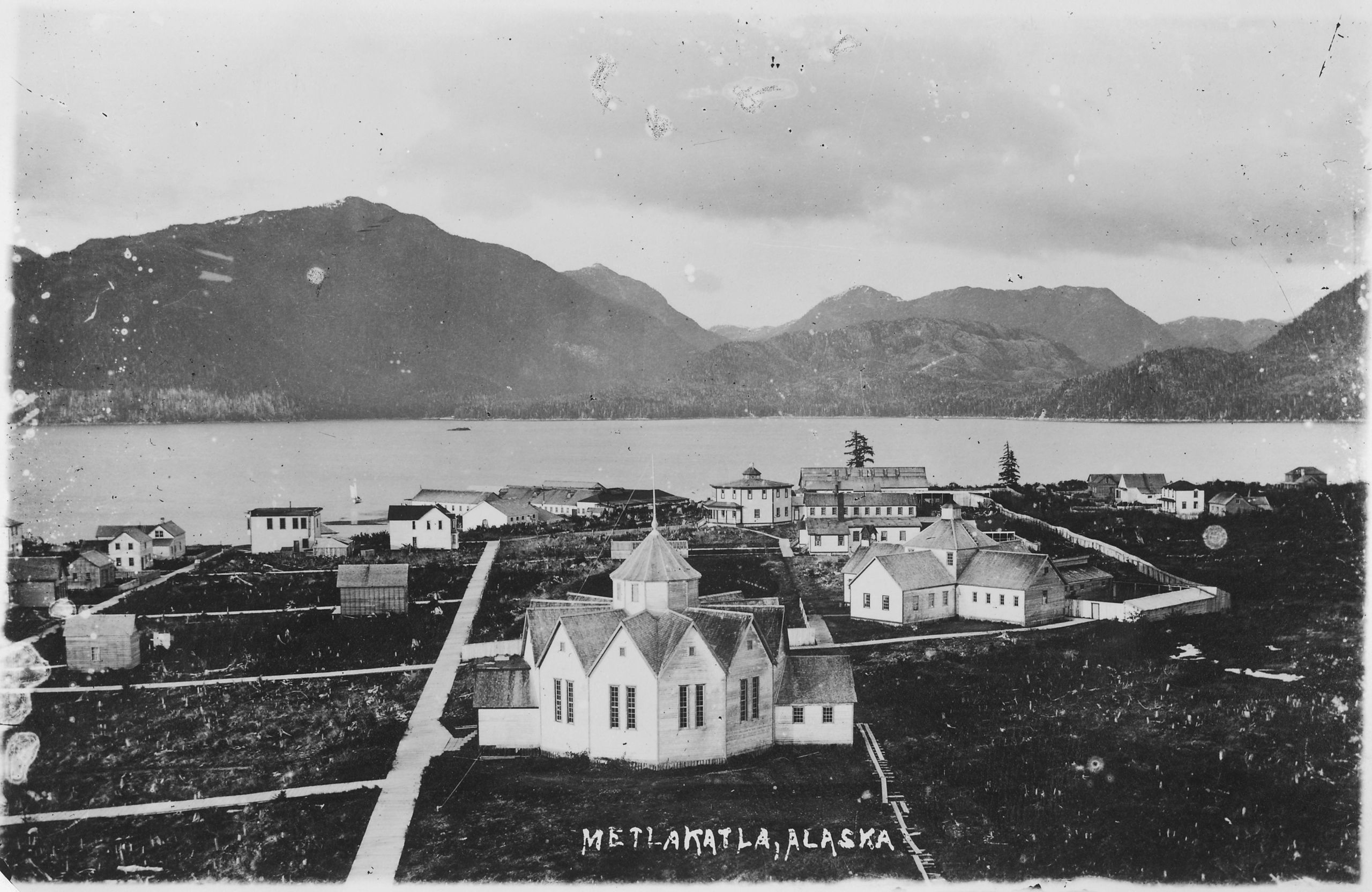

Here is the opinion in Metlakatla Indian Community v. Dunleavy.

Briefs are here.

Lower court materials here.

Non-decision, more like. Here are the materials in Silva v. Farrish:

Opinion here. Excerpt from the court’s syllabus:

We hold that Ex parte Young applies to the plaintiffs’ fishing-rights claims against the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (“DEC”) officials— but not against the DEC itself—because the plaintiffs allege an ongoing violation of federal law and seek prospective relief against state officials. We also hold that the plaintiffs have Article III standing to seek prospective relief and that Younger abstention no longer bars Silva from seeking prospective relief because his criminal proceedings have ended. We therefore conclude that the district court erred in granting summary judgment to the DEC officials on the plaintiffs’ claims for declaratory and injunctive relief. The district court properly granted summary judgment on the discrimination claims because there is no evidence in the record that would permit an inference of discriminatory intent.

Lower court materials here.

Here are the materials in Simmons v. State of Washington:

Here:

More details on the case here.

Here is the petition in Scudero v. Alaska:

Questions presented:

1. Can the State of Alaska by criminal prosecution and threat of fine and incarceration prohibit Alaska Native members of the Metlakatla Indian Community and Tribe and the Tsimshian Nation, who have vested broad off-reservation, aboriginal, treaty, presidential proclamation, and congressional legislature enacted, and granted, fishing rights, from harvesting fish in their traditional Pacific Ocean fishing waters, and Annette Islands Reserve related waters, which fishing is essential to their culture, heritage, and lifestyle, and vital to the very purpose for which the Reserve was established and dedicated, under the guise of “conservation necessity” by criminally banning those natives who are “un-permitted” i.e., do not have State of Alaska “limited entry permits,” which permits are bought and sold for many tens of thousands of dollars and well beyond the financial resources and means of most natives, and which permits were issued in a restricted and “qualifying fashion” that discriminates against those Metlakatla Natives?

2. Should this Court act as the United States Supreme Court did on two (2) prior occasions in Alaska Pacific Fisheries Company v. United States, 248 U.S. 78, 39 S.Ct.40, 63 L.Ed. 138 (1918) and Metlakatla Indian Community v. Egan, 369 U.S. 45, 82 S.Ct. 552, 7 L.Ed. 262 (1962), to protect the rights of the Tsimshian Nation members of the Metlakatla Indian Community and Tribe as to the Annette Islands Reserve, as to vested fishing rights relating to the Reserve, or allow the State of Alaska and the Alaska Supreme Court to abrogate and extinguish those aboriginal, treaty, presidential proclamation, and congressional legislation and grant rights [which abrogation involves native fishing rights that evolve from the Russian Treaty of Succession of 1867 (Alaska Acquisition Treaty) and subsequent federal legislation including the Alaska Statehood Act, (72 Stat. 339) Public Law 85-508, 85th Congress, H.R. 7999, July 7, 1958, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (“ANCSA,” 43 U.S.C. § 1601 et. seq.), and violation of the duties and obligations of the State of Alaska thereunder], with devastating impacts on the Metlakatlans and their thousands of years of culture tradition and heritage under the guise of the misapplied “conservation necessity principle,” where said misapplication is discriminatory against the Tsimshian Metlakatla Tribe and natives such as John Albert Scudero, Jr. and there will be no real impact on the Alaska limited entry fishing program or the fisheries of Alaska if the natives’ vested rights are honored?

3. Can the State of Alaska by such criminal prosecution abolish those Alaska Natives’ fishing rights when allowing the small number of Metlakatlans to exercise their rights will in reality have little impact on the State of Alaska Limited Entry Fisheries Program, or salmon fisheries; although such discriminatory ban and prohibition and criminal prosecution abrogates and emasculates those vested fishing rights and destroys the basic purpose for which the Reserve was established by presidential proclamation and congressional action, as a reserve for the Alaska Natives to enjoy and practice their historical and traditional fish harvesting lifestyle, as opposed to an agrarian lifestyle which was and is not possible on the Reserve; or does the State of Alaska have to honor those vested rights of the Alaska Natives, Metlakatlans, as the Courts have held as to vested native fishing rights and allow them to fish on equal footing and par with non-native fishers, merely perhaps equally subject to true conservation regulatory measures as to “manner and means,” and “seasons” of harvest and not subject to a criminal prosecution impressed discriminatory total ban on un-permitted natives so exercising their vested fishing rights?

Lower court materials here.

From Nicole Friederichs:

Suffolk Law’s Human Rights and Indigenous Peoples Clinic secures victory for indigenous communities in Guatemala.

On Friday, December 17, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled in favor of indigenous communities in Guatemala in the Case of Maya Kaqchikel indigenous community of Sumpango, et al. v. Guatemala. Suffolk University Law School’s Human Rights and Indigenous Peoples Clinic has been the legal representative of the four named indigenous communities in this case since 2012.

The Court ruled that the State of Guatemala violated the indigenous communities’ rights to freedom of expression and thought, culture, and non-discrimination by promoting a regulatory framework which prevented indigenous peoples from accessing radio frequencies to develop and operate community radio stations. The Inter-American Court ordered Guatemala to (1) adopt legislative and regulatory measures to ensure for the recognition of community radio, (2) reserve indigenous community radio as part of the radio spectrum and (3) to halt all government raids of existing indigenous community radio. This court victory culminates decades of advocacy by indigenous communities in Guatemala and indigenous organizations such as Cultural Survival, one of the petitioners in the case.

What is of particular significance is the Court’s recognition of indigenous peoples’ right to operate their own media, and the relationship of this right to freedom of expression, culture, self-determination, and non-discrimination. This is the first known international case to recognize this right and its recognition by the Inter-American Court should influence how other judicial and human rights bodies interpret and promote this right to media under the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The legal team was led by Nicole Friederichs, Director of Suffolk’s Human Rights and Indigenous Peoples Clinic, along with Suffolk Law Adjunct Prof. Amy Van Zyl-Chavarro. Suffolk Law Prof. Lorie Graham submitted expert testimony, on which the Court relied in its analysis of indigenous peoples’ right to media. Nicole Friederichs noted, “This decision is a victory not only for indigenous communities in Guatemala, but also for indigenous peoples throughout this hemisphere in protecting their rights to freedom of expression and culture and promoting pluralism in media.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.