This and other comprehensive state ICWA laws are kept here.

If your state doesn’t have a comprehensive state ICWA law, you should get one. For a lot of different reasons, they are vital to maintaining ICWA’s protections for Native families.

Since we all now have to deal with it, might as well deal with it together:

The Court granted the petition with no limitations, so the issues are not limited the way the government and four tribes requested. Arguments will be held next term (terms start in October, so after October, 2022).

Even though this is not an ICWA case, three people have sent me this opinion by Justice Montoya Lewis regarding the primacy of relative placement in child protection proceedings. This opinion points to all sorts of issues that beleaguers relative placement, especially certain aspects of background checks and prior involvement with the system. Here, the Court explicitly holds that prior involvement in the system alone cannot be consider as a reason to keep a child out of a relative placement, and seems to imply that both criminal history and immigration status cannot be considered either.

But no wonder the ICWA advocates noted this case–you can see ICWA’s influences implicitly and explicitly throughout:

This statutory scheme makes it clear that both the Department and the courts are directed by the legislature to preserve the family unit and, when unable to do so, to place the child with family members, relatives, or fictive kin before looking beyond those categories to nonrelatives.

***

This means that the dependency court is charged with actively

ensuring that relative placements have been fairly evaluated. This is an active

process required at each hearing. Id. Making a finding that no such family

placements exist at one hearing does not mean that the inquiry ends: the statute

contemplates that the inquiry is ongoing, recognizing that family circumstances

change, as they so often do, and as they did in this very case. Id.

(emphasis added)

Courts must do more than give a passing acknowledgment for relative preference,

as occurred in this case. Courts must actually treat relatives as preferred placement

options and cannot use factors that operate as proxies for race or class to deny

placement with a relative.***

Prior involvement with child welfare agencies, without more, can serve as a proxy for race or class, given that families of Color are disproportionately impacted by the child welfare system.11 [!!!!!!]

(emphasis and punctuation added and oh BY THE WAY what does that footnote 11 say?? Is it a very long footnote on ICWA, the gold standard?? Now THAT is a long footnote I don’t mind reading):

11 For example, under the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA)—the “gold standard” in child welfare policy—children in foster care or preadoptive placement “shall be placed in the least restrictive setting which most approximates a family” with highest preference to a member of the child’s extended family, absent “good cause to the contrary.” 25 U.S.C. § 1915(b); BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS , U.S. DEP ’ T OF INTERIOR, GUIDELINES FOR I MPLEMENTING THE INDIAN CHILD

WELFARE A CT 39 (2016). A party seeking to deviate from this placement preference must state their reasons on the record and bears the burden of proving by clear and convincing evidence that there is good cause to depart from the placement preference. 25 C.F.R. § 23.132(a), (b). One reason a court may conclude that there is good cause to depart from the placement preference is the unavailability of a suitable placement, but “the standards for determining whether a placement is unavailable must conform to the prevailing social and cultural standards of the Indian community in which the Indian child’s parent or extended family resides or with which the Indian child’s parent or extended family members maintain social and cultural ties,” and socioeconomic status may not be a basis to depart from the placement preference. 25 C.F.R. § 23.132(c)(5), (d). Notably, prior contact with the child welfare system, criminal history, and poverty are not good cause reasons to depart from the strong preference for placement with relatives under ICWA. Likewise, tribes located around Washington State prioritize placement with extended family or other members of the tribal community and rarely treat factors like prior child welfare proceedings or criminal history as disqualifying in determining out-of-home placements for children. See, e.g., NISQUALLY TRIBAL CODE § 50.09.09; NOOKSACK LAWS & ORDINANCES § 15.09.100; JAMESTOWN S’ KLALLAM TRIBE T RIBAL CODE § 33.01.09(J); PUYALLUP TRIBAL C ODE § 7.04.840. But see TULALIP TRIBAL CODE § 4.05.110(4) (prohibiting placement with someone with a criminal conviction, but only for certain crimes identified as disqualifying crimes by the social services division charged by the Tulalip Tribe with the responsibility to protect the health and welfare of Tulalip families and their children (beda?chelh)).

Finally, “Courts must afford meaningful preference to placement with relatives.” (not my emphasis this time)

The Washington Supreme Court is doing very important work right now, as are some of the best child protection activists/litigators in the country (IYKYK).

Here (zoom webinar link here):

Fletcher and Singel will discuss their forthcoming paper, “Lawyering the Indian Child Welfare Act.”

DSS and the guardian ad litem for Carrie (GAL) disagree, arguing that respondent

conflates the existence of or possibility of a distant relation with an Indian with

reason to know that a child is an Indian child.

States and courts are really struggling with how much information from a parent gives the court reason to know there is an Indian child in the case–I think this is especially since the regulations now make clear that if you do have reason to know, you must treat the child as an Indian child until demonstrated otherwise. At the same time, there is real issue with lack of nuance on this issue–when a trial court takes the facts from a case like In re Z.J.G. and treats them the exact same way as the facts in this case, which is essentially what happened, then states really have to go send notice for both, which is what the WA Supreme Court held. You don’t do the reverse, which is what the North Carolina Supreme Court has done in this case.

Now, I got an email from California recently and there is a lot of discussion there about the state’s laws there distinguishing between “reason to believe” and “reason to know.” There are a LOT of bumps with implementation, but they are essentially requiring a level, or duty, of inquiry and further inquiry from their state workers to ensure they aren’t missing ICWA cases.

I’d love to get into why is the GAL arguing against the application of ICWA or ensuring the child has the information she may need to be a tribal citizen, but I do have to do some other things today . . . https://turtletalk.blog/2013/11/25/fletcher-fort-indian-children-and-their-guardians-ad-litem/

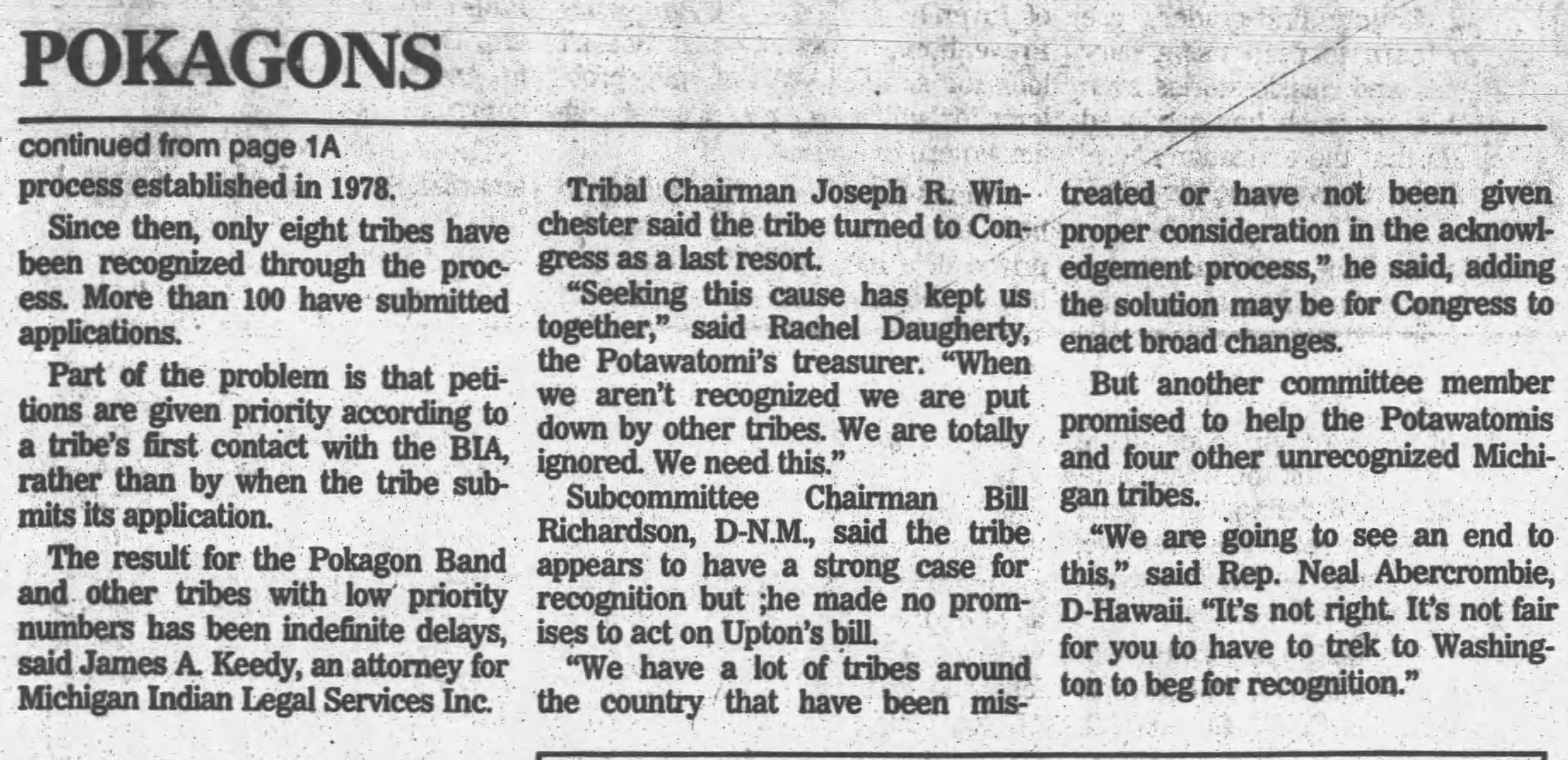

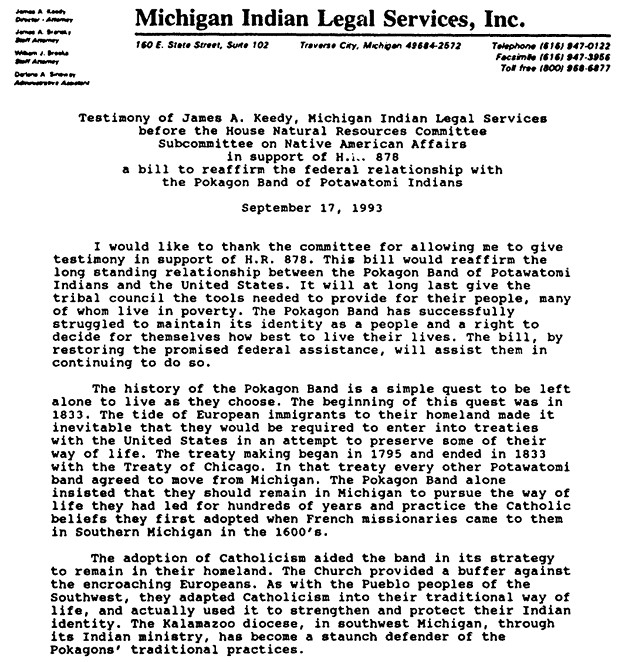

Traverse City Record-Eagle notice here. From the statement issued by Michigan Indian Legal Services:

| Jim Keedy was living proof of how fine a person can be. He was an excellent boss to the people and programs in his charge and a devoted husband to his wife, Cathy. He was also a good friend to many and a great colleague. The character of his life might be summed up in a few words: sincere, earnest, loyal. Jim was a long-time poverty law attorney and was dedicated to the ideal of accessible legal aid, developing extensive outreach programs for Native rural communities in remote areas. He was also passionate about the importance of children being able to remain in their families and was an early champion for parents under the Indian Child Welfare Act and the Michigan Indian Family Preservation Act. Under Jim’s leadership, MILS provided assistance to 5 tribes obtaining federal recognition – the government-to-government relationship that allows for tribes to be able to successfully provide for their communities. He also believed in responsible government and was a champion for the individuals facing the weight of the system on them in tribal court cases. We will long remember Jim’s tenacity, and ability to meet difficult challenges. Jim was a brilliant and visionary leader who achieved recognition for his work in the underserved Native American communities. Jim was the proud recipient of State Bar of Michigan American Indian Law Section’s Tecuseh Peacekeeping Award in 2004; the State Court Administrative Office (SCAO) Foster Care Review Board’s Parent Attorney of the Year in 2018; the National Legal Aid and Defender Association’s Pierce-Hickerson Award also in 2018; and the Michigan State Bar Foundation’s Access to Justice Award in 2020. As Executive Director at Michigan Indian Legal Services for over 30 years, Jim led his staff in such a way that he exemplified leadership. He gave inspiration to his team and others he worked with. The Jim we remember was always courteous, kind, and generous. He had a beautiful smile, a sense of humor, and a gentle demeanor. Jim was a genuinely wonderful individual—one we will miss greatly. As an attorney, Jim worked with passion, integrity, and honor. By his death, all the people who knew him will miss a brilliant individual with a rare friendliness and charm of personality. Our sorrow is slightly lessened with the comforting thought that we had the privilege of knowing him. Baa Maa Pii, Jim. |

Jim was a well-known figure in Michigan Indian country. I first became aware of him when he worked on the federal recognition for the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians. He testified before Congress in 1993 and 1994 in support:

I’m still cleaning the data for the 2021 ICWA cases, but here are a few screen shots that might be interesting. Federal cases are excluded. This dataset is based on my reading of Lexis/Westlaw alerts as well as a few individual state alerts. Mistakes are mine.

The Colorado Court of Appeals analyzed the regs on the reason to know issue, a similar argument to the In re Z.J.G. case from Washington. And as in Z.J.G., the Department is arguing for a narrower interpretation. However, the Court of Appeals reasoned:

Recall that the federal regulation and the Colorado statute implementing ICWA’s “reason to know” component distinguish between information that the child is an Indian child, 25 C.F.R. § 23.107(c)(1); § 19-1-126(1)(a)(II)(A), and information indicating that the child is an Indian child, 25 C.F.R. § 23.107(c)(2); § 19-1- 126(1)(a)(II)(B). These two provisions cannot have the same meaning because that would make one superfluous.

***

As a result, divisions of this court have repeatedly recognized that, where a district court receives information that the child’s family may have connections to specific tribes or ancestral groups, the court has “reason to know” that the child is an Indian child — even where the information itself does not establish that the child fully satisfies the definition of an Indian child

You must be logged in to post a comment.