Here is the brief in Trump v. Barbara:

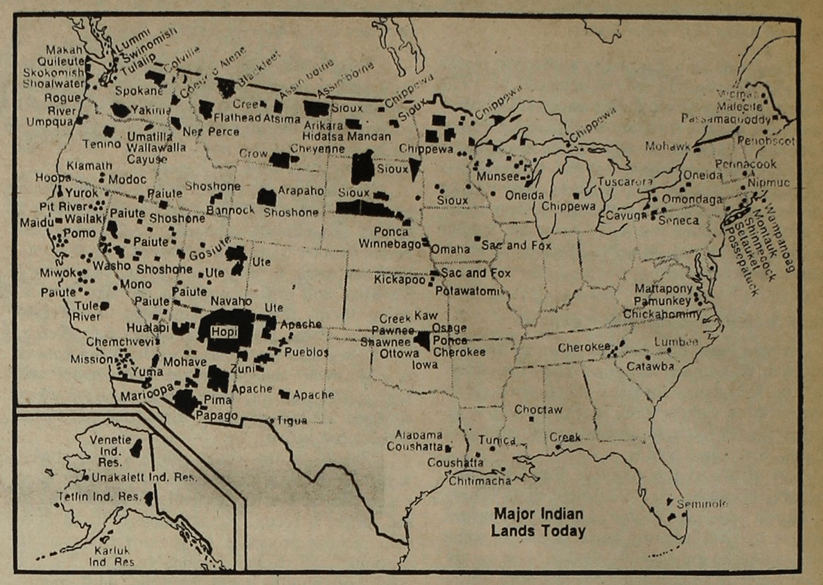

On December 15, 2025, the U.S. District Court for the District of Montana approved a settlement reached in Chippewa Cree Indians of the Rocky Boy’s Reservation v. Chouteau County, Montana that will provide Tribal citizens the opportunity to elect a representative of their choice to the Chouteau County Board of County Commissioners.

Under the terms of the settlement, the Tribal Nation’s reservation will be part of Chouteau County’s District 1, which will elect a representative to the Board of County Commissioner through a single-member district election.

“We’re pleased that the county did the right thing in giving the Chippewa Cree Tribe a chance to elect a representative to the Board of Commissioners,” said Chippewa Cree Tribe Chairman Harlan Gopher Baker. “It has been more than a decade since we have had a Native voice in county politics. We look forward to being a part of this conversation.”

“This case was about our community finally having a representative and a voice like other voters in the county,” said plaintiff and voter Tanya Schmockel, a citizen of the Chippewa Cree Tribe. “I am excited about finally having the chance to have our voices heard and our concerns addressed.”

Most of Chouteau County’s Native population lives on or near the Rocky Boy’s Reservation, and many critical local issues — such as infrastructure, road maintenance, and emergency services — require coordination between the county and Tribal governments.

“In order for our county to include all of us, we needed a fair election system. With the new district, we have a chance for our voters to elect a commissioner who understands Native issues,” said plaintiff and voter Ken Morsette, a citizen of the Chippewa Cree Tribe. “This is a huge step forward for our Tribe.”

Native American Rights Fund (NARF), American Civil Liberties Union Foundation Voting Rights Project (ACLU), and ACLU of Montana (ACLU-MT), represent the plaintiffs in this case.

Read more about the Tribe’s successful fight for fair voting in Chouteau County.

Teresa M. Miguel-Stearns, Samantha Ginsberg, and Kristen Cook have posted “More Than Morrill: The Intertwined History of Indian Land Dispossession, Arizona Statehood, and University Enrichment,” published by the Arizona Journal of Environmental Law and Policy, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

Through the federal government’s university land-grant programs, which began with the Morrill Act in 1862 and continue today, Congress has systematically allocated millions of acres of land in the western United States to states to create endowments to support the public higher education of its citizens. In Arizona, land was taken from Indigenous peoples, communities, tribes, and nations by treaty, act of congress, executive order, and force to accomplish this. As a result, by the time of statehood in 1912, the state of Arizona had accumulated approximately 850,000 acres of land around the state on behalf of higher education, including the University of Arizona, then the state’s only university and its designated land-grant institution. Today, the Arizona State Land Department still holds and manages 688,706 acres of land in trust for the benefit of public higher education. All three of Arizona’s public universities receive distributions from the revenue generated by these trust lands. The goal of this paper is to explore and analyze the University of Arizona’s historical and ongoing enrichment from land taken from Indigenous peoples by the federal government and transferred to the territory and, later, the state of Arizona in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for the benefit of institutions of higher education. A comprehensive understanding of Arizona’s history and the state’s current holdings and financial benefits is required to examine the policy implications and moral and legal obligations that Arizona and its universities have to Indigenous peoples in Arizona.

Christian McMillen has published “I Didn’t Know That a Patent Was a Dangerous Thing”: Forced Fee Patents, Native Resistance, and Consent” in the Western Historical Quarterly.

Here is the abstract:

Between 1906 and 1920 the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) issued more than 32,000 fee patents, covering 4.2 million acres of land. More than half of the patents were issued between 1917 and 1920. The BIA forced many of these patents upon Native people without their consent. When individually allotted land went from trust to fee, the land was taxed and could be sold. The consequences were devastating. Was this legal? Many Native people protested their fee patents, but others did not. Indeed, protesting dispossession was an act of courage and defiance. Native protest led to a legal precedent that had an impact across Indian country: consent was required. But was compliance synonymous with consent? Must one resist a policy found to be illegal in order for it not to apply? For a time, the answer was yes. Ideas about consent began to change leading to another series of legal challenges to the Bureau’s forced fee patent policy.

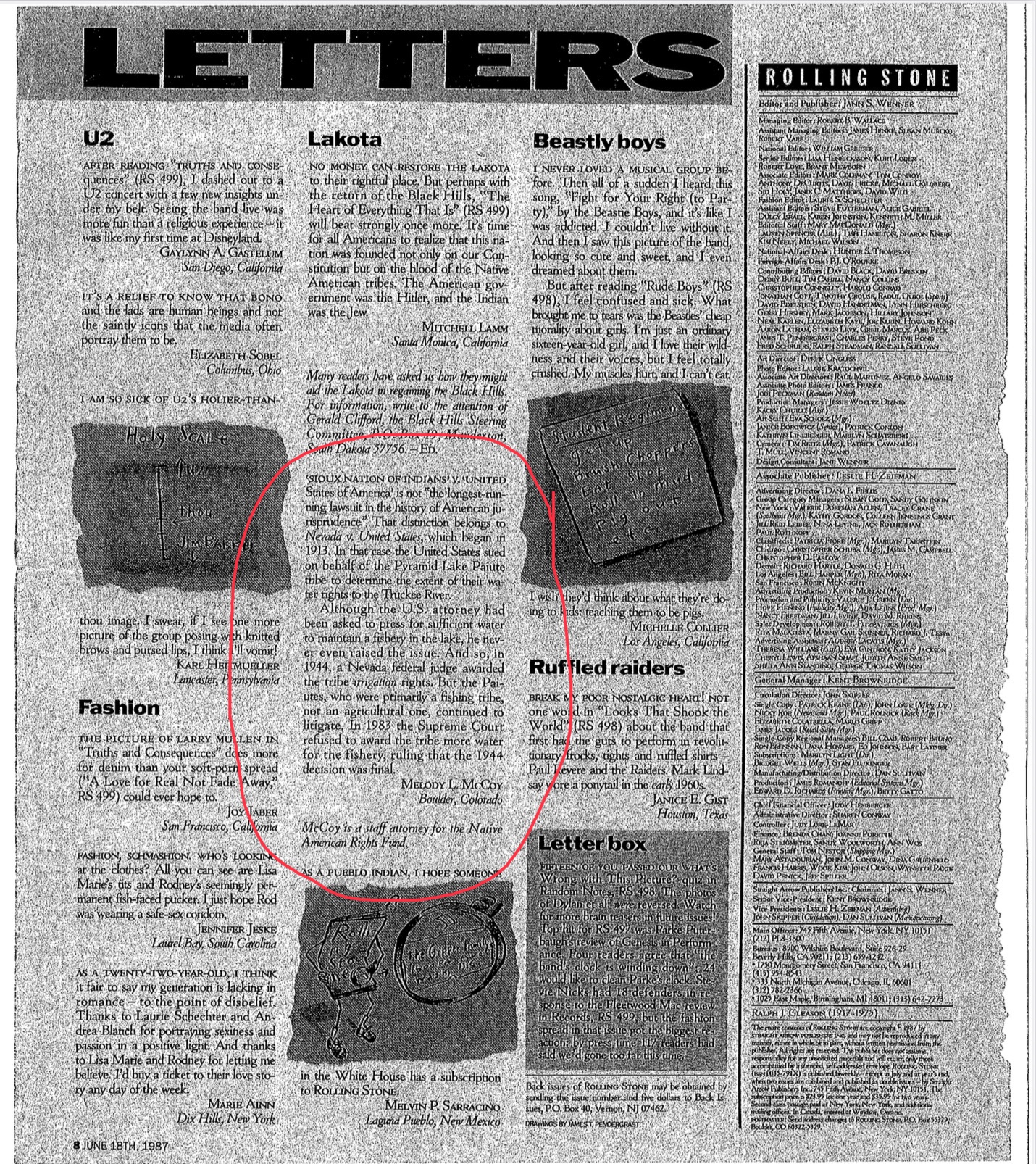

There was an error in that Rolling Stone article that led Melody McCoy to write a correction in 1987:

You must be logged in to post a comment.