Erica Liu has published “The Cartographic Court” in the NYU Law Review.

Here is the abstract:

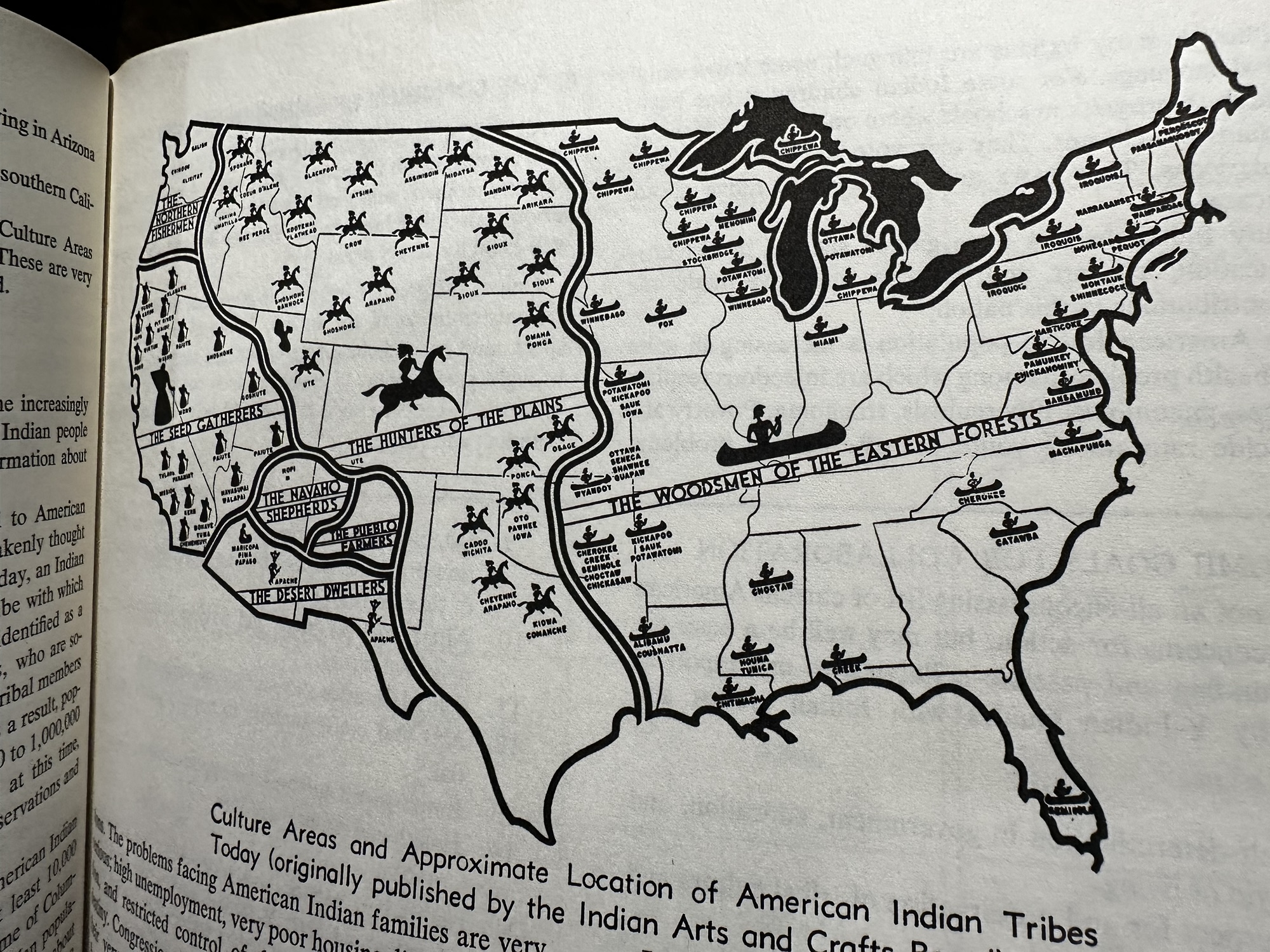

Over the past few decades, the Supreme Court of the United States has adopted an exceedingly narrow view of tribal civil jurisdiction, establishing doctrines that restrict the circumstances in which Native Nations can exercise their regulatory and adjudicative powers. While most scholarship in federal Indian law has assessed this judicial trend towards tribal disempowerment by focusing on the Court’s treatment of tribal sovereignty, this Note centers the Court’s manipulation of tribal territory. It argues that the Court has constructed three territorial incongruities—non-Indian fee lands, public access, and loss of “Indian” character—to justify the disallowance of tribal authority over significant portions of tribal reservations. In so doing, the Court relies on a spatial imaginary of territorial sovereignty, or the notion that sovereign power must be commensurate with sovereign domain, to present certain spaces as falling outside of a Native Nation’s territory and, accordingly, as beyond the reach of its jurisdictional power.

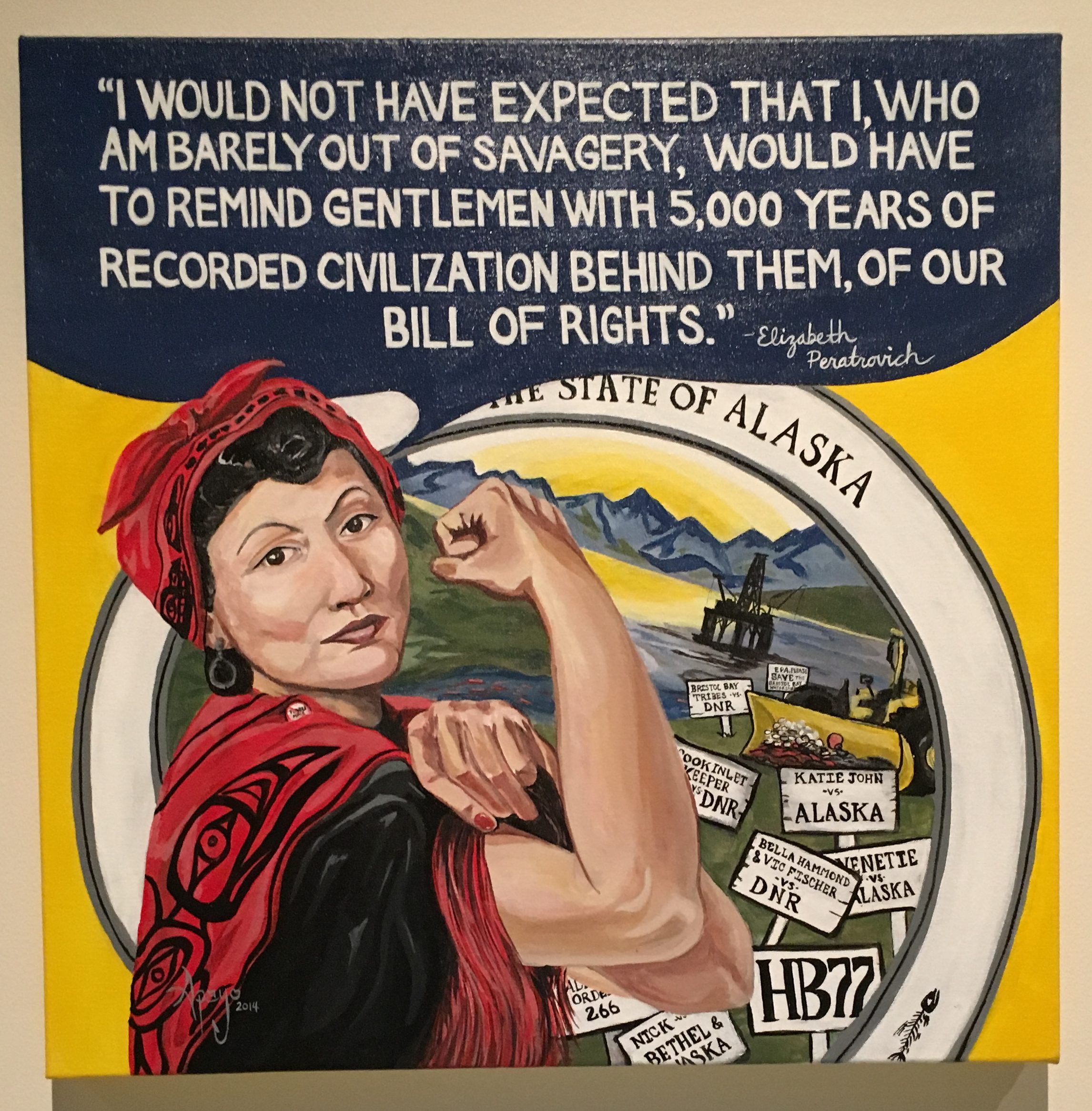

By illuminating the spatial imagination of the Supreme Court, this Note identifies a key practice employed by the Court that is central to empires past and present— cartography. The Court superimposes its own imagined legal geography upon the preexisting system of territorial division, redrawing the jurisdictional boundaries that separate states and Native Nations. This practice of spatial manipulation is cartographic in that it allows the Court to determine and limit the territory of tribal rule; to expand the areal authority of state jurisdiction; and to project its particular vision of reservation lands—a vision defined by notions of ownership, accessibility, and character—upon Indian country. These cartographic tactics of territorial acquisition and control are in direct furtherance of the American colonial project. They fragment tribal regulatory regimes, reify Indigenous life, and transfer congressional power to the Court to diminish tribal reservations. These practices of fragmentation, reification, and de facto diminishment are continuations of the repudiated but never-undone federal policy of allotment, although the main perpetrator is now the Court rather than Congress.

By turning to critical legal geography and theories of space and power, this Note reveals a Supreme Court that is highly imaginative, overtly spatial, and problematically cartographic in nature, engaged in a project of colonial expansion across its tribal civil jurisdiction cases.

You must be logged in to post a comment.