Ann Estin has posted “Equal Protection and the Indian Child Welfare Act: States, Tribal Nations, and Family Law,” forthcoming in the Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

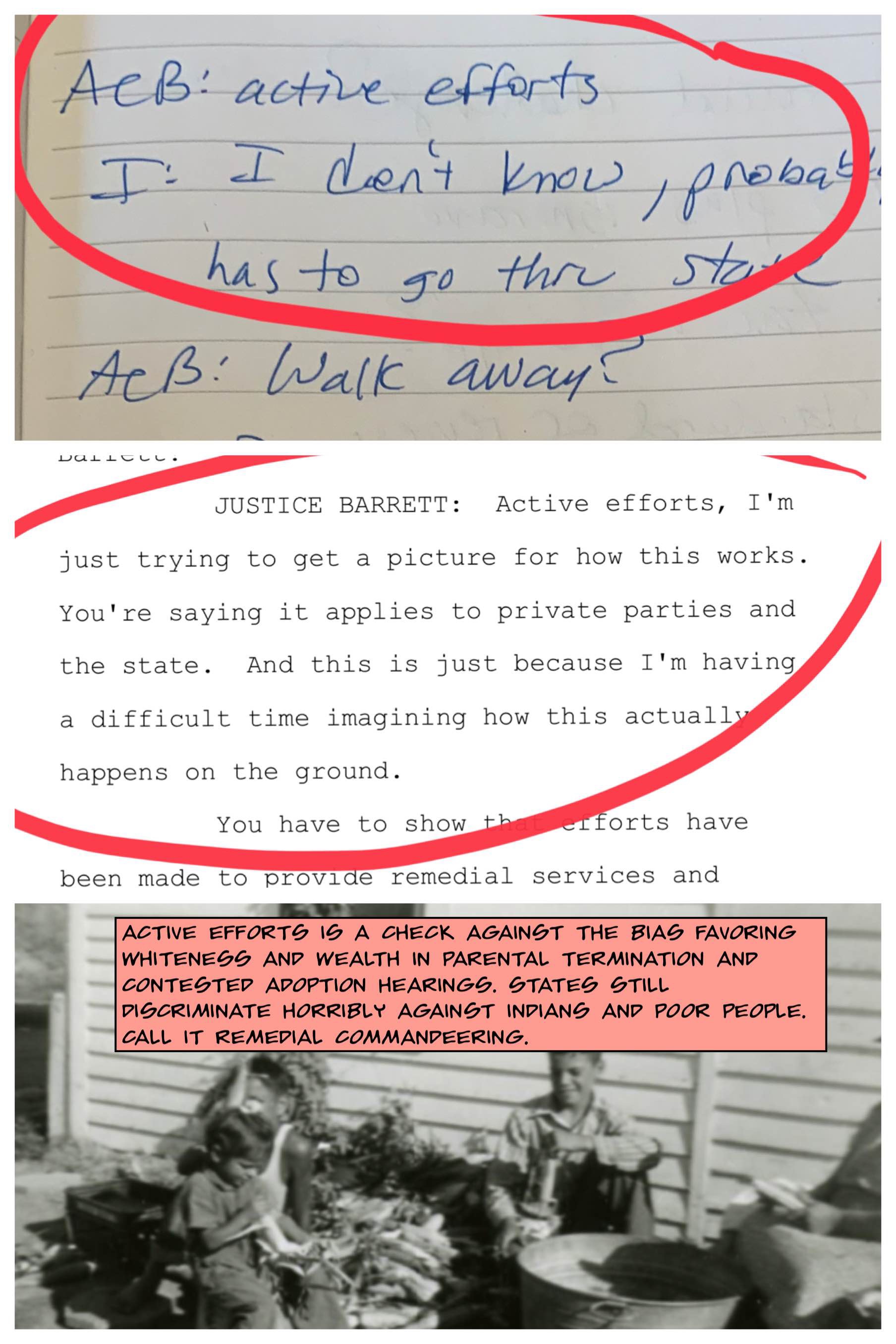

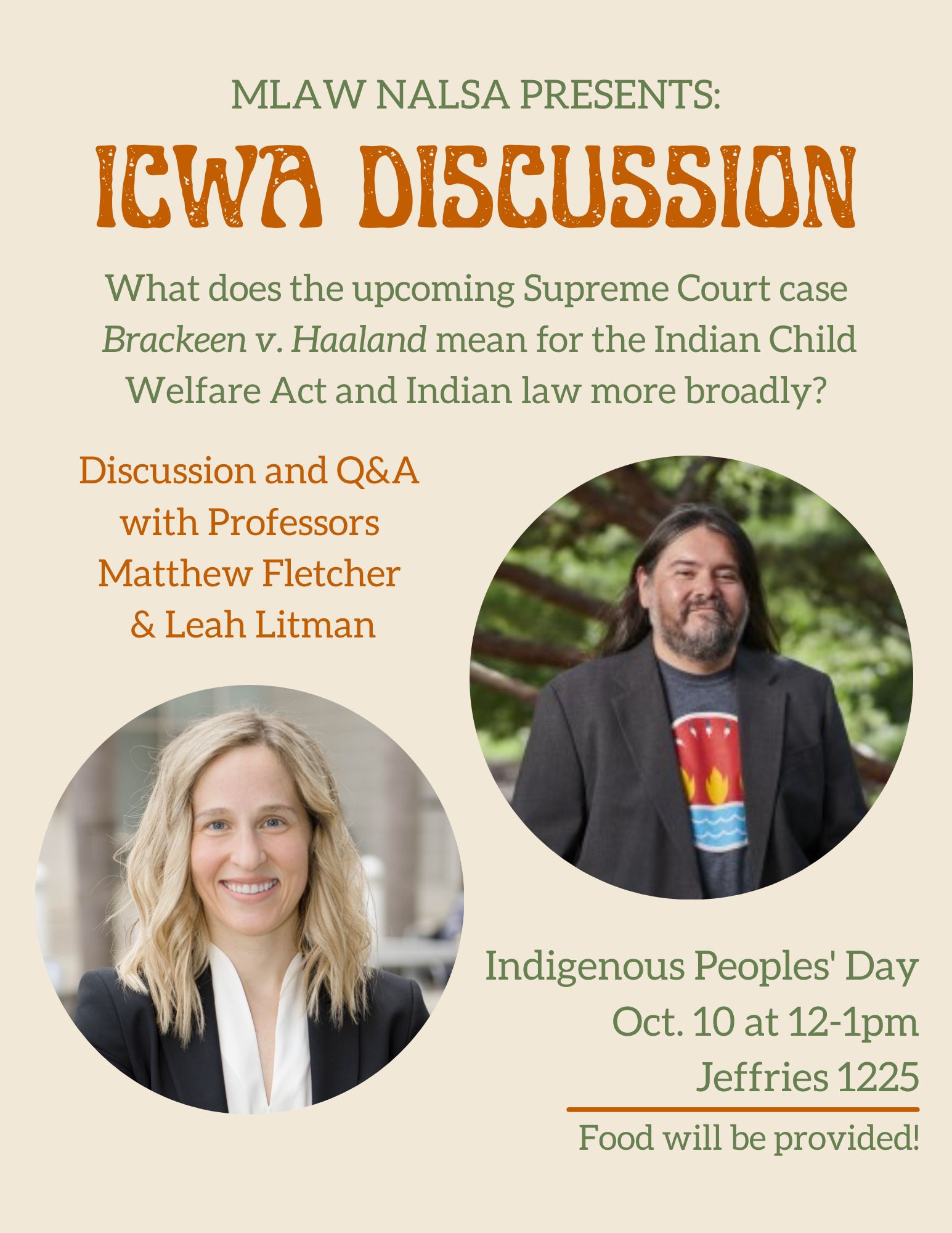

Congress has long exercised plenary power to set the boundaries of federal, state and tribal jurisdiction, and Supreme Court precedents have required that such legislation be tied rationally to the fulfillment of Congress’s unique obligation to Indian tribes. Exercising this power, Congress set parameters for state and tribal jurisdiction in child welfare and adoption cases with the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (ICWA). In response to the recent Equal Protection challenge to ICWA by a small number of states in Haaland v. Brackeen, many more states have argued in support of the legislation, which addressed longstanding problems in the states’ treatment of Indian children and provided an important framework for cross-border cooperation in child welfare cases. Looking beyond ICWA, this article points to unresolved jurisdictional and conflict of laws challenges in other types of family litigation that crosses borders between states and Indian country. Arguing that citizens of tribal nations should have the same right to bring family disputes to courts in their communities that other Americans enjoy, the article argues for greater cooperation and comity between states and tribes across the spectrum of family law.

You must be logged in to post a comment.