Here are the new materials in United States v. Abouselman (D.N.M.):

Prior post here.

Here are the new materials in United States v. Abouselman (D.N.M.):

Prior post here.

John W. Ragsdale has posted “The Aboriginal Land and Water Rights of the Jemez Pueblo,” forthcoming in the Denver University Water Law Review, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

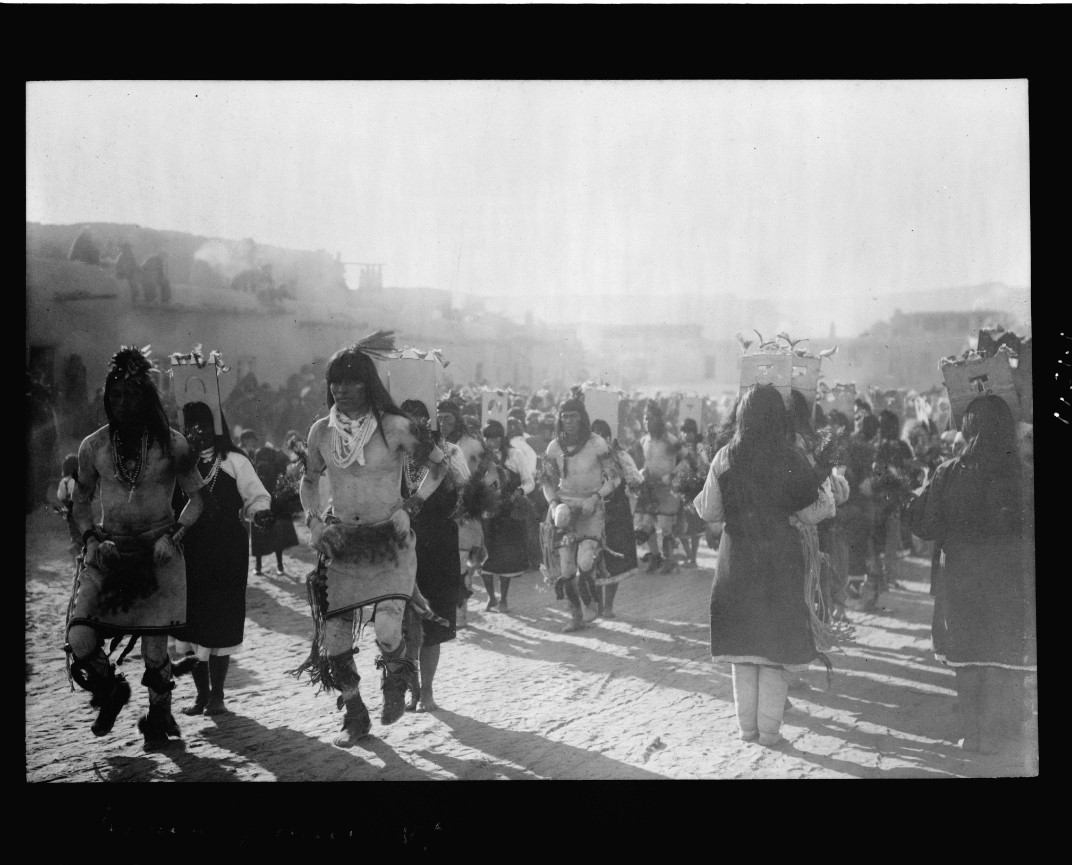

Since time immemorial, the indigenous people of what became the Southwest United States have maintained sustainable, vibrant communities in the harshest of environments; one with generally arid climate, inconsistent precipitation, heat, wind, thin soil and erosion. These communities, on the razor’s edge, survived for eons because resilience and community, within and with the land, were at the center of their life, economy and order. Balance was not always perfect, but it was the target. The possibility of economic surplus and growth is perhaps a latent human instinct, but it until the fluorescence of Chaco Canyon in the eleventh century it remained subordinate. With the fall of Chaco and eventual restoration of decentralizations and the traditional aboriginal practices, balance returned.

The European invasion and the infusion of competitive individualism and economic growth changed all this. The movement west on the wings of the doctrine of discovery and the ensuing extinguishment of both aboriginal title and the stable-state economies proceeded across the Mississippi and the prairies and slammed the capitalistic wrecking ball into the most resilient of the aboriginal survivors – The Pueblo Indians of the Southwest.

The Jemez Pueblo of Central New Mexico has been one of the fiercest defenders of the traditional aboriginal community. Through the intrusion of Spain, Mexico and ultimately the United States, the Pueblo clung to its central land, its claims to aboriginal surroundings and water, and its sustainable orientation, this article traces the prehistoric courses of the Pueblo, and it centuries-long efforts to maintain both the focus and the legal existence of its aboriginal community. It has not been a complete victory in the dominant sovereigns’ courts, but the aboriginal heart of the people and possibilities for collaboration with other Tribes and, perhaps, with a more generous and enlightened dominant sovereign, remain strong.

Here are the en banc stage materials in United States v. Abouselman:

Order Denying Petition for Rehearing

Panel materials here.

Here is the opinion in United States v. Abouselman.

Briefs and lower court materials here.

Here are the available materials in United States v. Abousleman (D.N.M.):

Here.

This information is from a press call with Asst. Sec. Larry Echohawk and Dep. Asst. Sec. Del Laverdure. A press release with fact sheets on each determination is here.

Four Indian gaming applications decisions:

1 positive Secretarial exception determination for Enterprise Rancheria of Maidu Indians, Butte Co., California, for a facility in Yuba County, California, 36 miles from existing headquarters.

1 positive secretarial exception determination for North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians, for a gaming facility in Madera County, CA, 36 miles from tribal land base.

1 negative decision for Pueblo of Jemez, for gaming facility in Anthony, NM, nearly 300 miles from existing reservation. The decision was based on land into trust regulations, not gaming regulations. Land into trust regs require looking into use for land and distance from Pueblo. Concern was exercising actual government power over a gaming site nearly 300 miles way. Agreements with local units of government meant that local governments would be exercising the governmental power, not the Pueblo.

1 negative decision for Guidiville Band of Pomo Indians, restored for federal recognition in 1991, for gaming facility in Richmond, CA (S.F. Bay Area), more than 100 miles from gaming site. Decision was based on regulations concerning the Rancheria’s historical and modern connections to the land.

You must be logged in to post a comment.