Here, authored by Kieran Murphy. PDF

An exceprt:

First, tribal courts are not, as Judge Bumatay suggested, “subordinate to the political branches of tribal governments.”68 For support, Judge Bumatay cited to Duro v. Reina,69 which cites to the 1982 edition of Cohen’s Handbook of Federal Indian Law.70 But tribal courts have changed since 1982: The 2024 edition of Cohen’s Handbook states that “[t]he structure of tribal courts is often similar to that of state courts” and “[p]rinciples of judicial independence have strong and growing roots in tribal courts.”71 Increasingly, tribes are “professionaliz[ing] the[ir] judiciar[ies]” in ways that “insulate them from tribal political pressure.”72

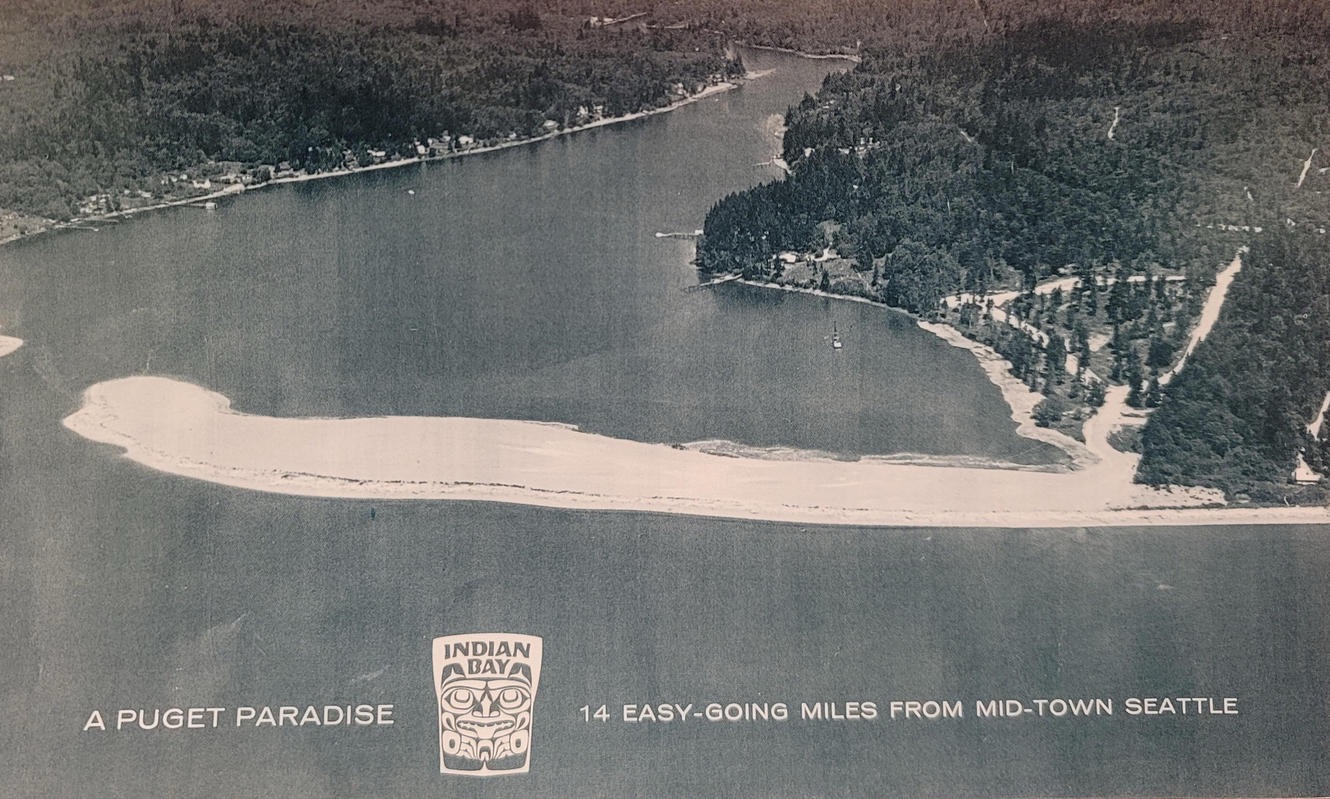

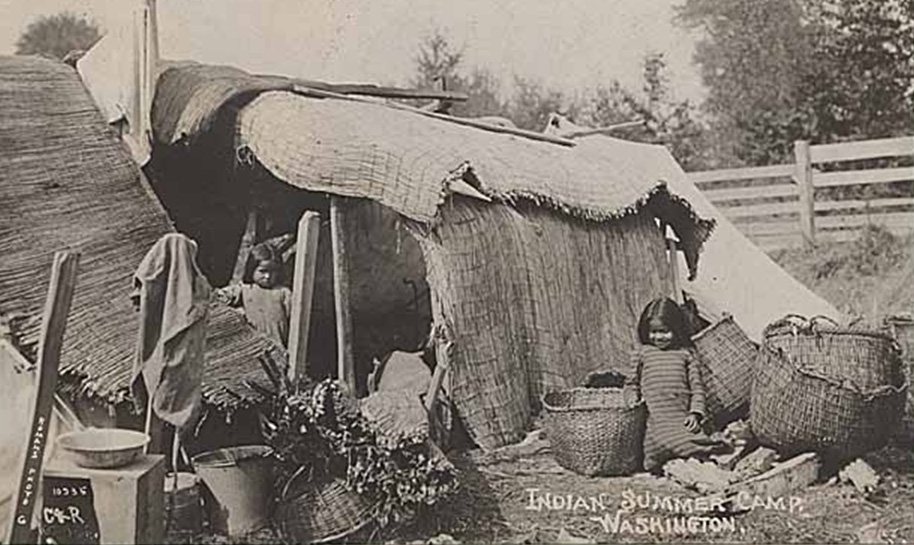

The Suquamish Tribe itself is illustrative. Judges are appointed by the Suquamish Tribal Council, which may alter judges’ powers or set salaries only at the time of judicial appointment.73 And judges are removable by a two-thirds vote of the Tribal Council, but only for “misfeasance in office, neglect of duty,” “incapacity,” or “convict[ion] of a criminal offense.”74 Judicial independence is thus a central feature of the Suquamish judiciary, as it is in many tribal courts.

Next, contra Judge Bumatay’s assertion that “tribal courts don’t rely on well-defined statutory or common law” but on values “expressed in [their] customs, traditions, and practices,”75 tribal law is “written, knowable, and publicly available.”76 Tribal constitutions, codes, and judicial opinions, including those of the Suquamish Tribe, are available from tribal governments, often online.77 While it is true that some tribal courts use traditional, nonadversarial practices to resolve internal disputes,78 those courts do not typically apply them to nonmembers, but instead use common law from the Anglo-American tradition.79 And tribes have little incentive to apply unknown or unfair tribal law to nonmembers given the Supreme Court’s anxiety about that possibility.80

Finally, Judge Bumatay misunderstood tribal law when he wrote that “because the tribes lie ‘outside the basic structure of the Constitution,’ the Bill of Rights, including the rights of due process and equal protection, doesn’t apply in tribal courts.”81 As Judge Smith noted in her Suquamish Tribal Court opinion, the “Indian Civil Rights Act . . . guarantees the right of due process under the law.”82 Furthermore, “[t]he test for due process in tribal courts is no different than for state or federal courts.”83 Federal courts ensure that a tribal court’s exercise of personal jurisdiction over nonmembers complies with the Fourteenth Amendment.84 And the criminal procedure protections of the Bill of Rights are inapplicable, as tribal courts may not exercise criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians.85

Judge Bumatay specified only one constitutional concern: “[W]ithout any constitutional backstop, tribal suits are almost exclusively tried before tribe-member judges and all-tribe-member juries.”86 For support, he cited to a footnote in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe,87 which states that tribes are “not explicitly prohibited from excluding non-Indians from the jury” and that the Suquamish tribal code provides “that only Suquamish tribal members shall serve as jurors in tribal court.”88 But Oliphant does not say that tribal courts employ “almost exclusively . . . tribe-member judges and . . . juries.”89 To the contrary, many tribal juries do include nonmembers,90 while some do not rely on juries for civil cases at all.91 And tribes, including the Suquamish Tribe, regularly hire judges who are nonmembers or non-Indian altogether.92

You must be logged in to post a comment.