Here are the new materials in Alegre v. United States (S.D. Cal.):

Prior post here.

Here are the new materials in Alegre v. United States (S.D. Cal.):

Prior post here.

This is a really interesting opinion, and balances a lot of interests. The issue of how to get a child who is both eligible for tribal membership and in foster care leads to a lot of questions about who gets to make the decision of enrollment. The agency has technical decision making authority for the children, but may choose to not enroll the children–as they did in this case–thus denying the application of ICWA (and a whole host of other citizenship related benefits and responsibilities). It may even mean the child can never be members, since some tribes don’t allow adults over the age of 18 to enroll. The Colorado Court of Appeals has just decided that the Court must make the final decision in those cases about whether a child should be enrolled or not.

In this case, mom told the agency the dad had Chickasaw heritage. This was enough for the agency to send notice to the Tribe. The Tribe responded that both the dad and the children were eligible for membership in the tribe, send membership applications, and asked the agency to assist the parents in enrolling the children.

The agency did NOT enroll the children, and did NOT tell the court of the Tribe’s response. The court only became aware of the response in the petition for termination. The court found ICWA did not apply, and terminated mom’s rights. The Court of Appeals determined that was not appropriate, and has created the process of an “enrollment hearing,” where the agency must deposit the Tribe’s request for enrollment with the court, and then the court must have a hearing–

Thus, once the response from the tribe has been deposited

with the juvenile court as set forth in Part II.B, we conclude that the

court must set the matter for a hearing to determine whether it is in

the best interests of the children to enroll them in the tribe. See

People in Interest of L.B., 254 P.3d 1203, 1208 (Colo. App. 2004) (A

juvenile court “must conduct a hearing to determine the proper

disposition best serving the interests of the child.”).¶ 23 Of course, at an enrollment hearing, as at any other hearing in

a dependency and neglect proceeding, the court must give primary

consideration to the children’s best interests. See K.D., 139 P.3d at

698; C.S., 83 P.3d at 640.¶ 24 And, in determining the children’s best interests, the juvenile

court must hear and consider the positions of the parents, as well

as the department and the guardian ad litem (GAL), all of whom

have standing, as relevant here, to speak to the merits of the tribe’s

enrollment request.

Though everyone can be heard, the court goes on to say,

Thus, at an enrollment hearing, the juvenile court should not

treat an objection, even from a parent, as a veto. On the contrary,

any reason for objection must be compelling considering ICWA’s

intent to maintain or foster the children’s connection with their

tribal culture.

Of course, the Tribe sent that letter requesting assistance enrolling the children in October of … 2018. Which means, of course, the twins who were a month old in May, 2018 are now two years old, never had any ICWA protections, and will now have their case go back to the trial court for a membership determination and a re-do of their child welfare case.

Here are the materials in Reyes v. Dept. of the Interior (S.D. Cal.):

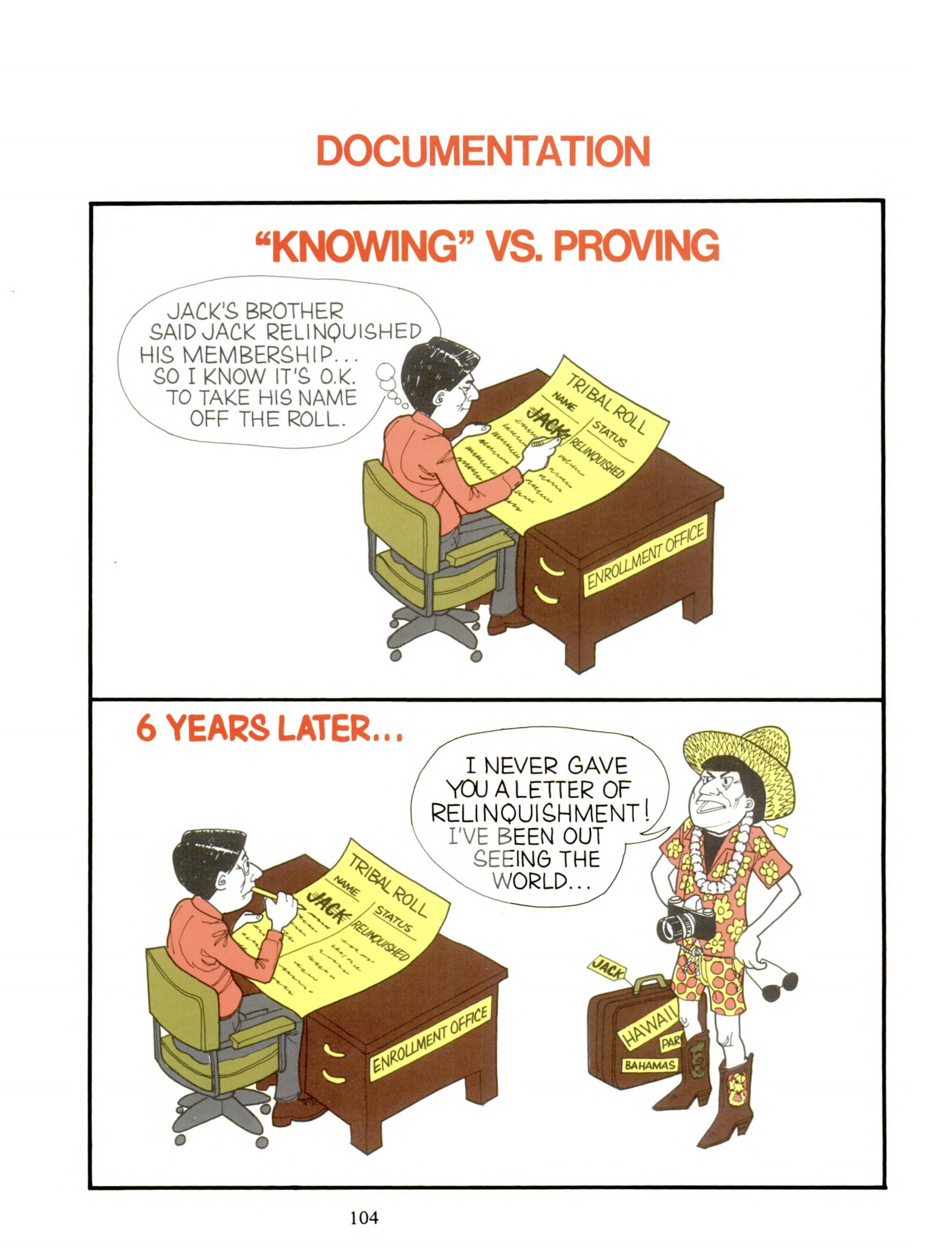

Yesterday, we covered tribal constitutions. Today, the political and bureaucratic complexity of enrollment decisions in cartoon form (we will conclude tomorrow):

Apparently, in 1977 or so, the Phoenix Area Office decided to write a lengthy manual for tribal governments, instructing them on how to make enrollment decisions that met tribal constitutional muster. Suffice it to say the text is TL:DR, but the illustrations are awesome — and by awesome, I mean crazy — and by crazy, I mean Indian country crazy.

Tomorrow, how tribal governments make membership decisions….

Here are the materials in Alegre v. United States (S.D. Cal.):

50-1 Individual Defendants MTD

Here is the order in Muscogee Creek Indian Freedmen Band v. Bernhardt (D.D.C.):

Briefs here.

Here, on SSRN.

The abstract:

The question whether Congress may create legal classifications based on Indian status under the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause is now reaching a critical point. Critics claim the Constitution allows no room to create race or ancestry based legal classifications. The critics are wrong.

When it comes to Indian affairs, the Constitution is not colorblind. Textually, I argue, the Indian Commerce Clause and Indians Not Taxed Clause serve as express authorization for Congress to create legal classifications based on Indian race and ancestry, so long as those classifications are not arbitrary, as the Supreme Court stated a century ago in United States v. Sandoval and more recently in Morton v. Mancari.

Should the Supreme Court reconsider those holdings, I suggest there are significant structural reasons why the judiciary should refrain from applying strict scrutiny review of Congressional legal classifications. The reasons are rooted in the political question doctrine and the institutional incapacity of the judiciary. Who is an Indian is a deeply fraught question to which judges have no special institutional capacity to assess.

Here:

You must be logged in to post a comment.