Here are the materials in Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. v. Mundahl (D. S.D.):

Here are the materials in Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. v. Mundahl (D. S.D.):

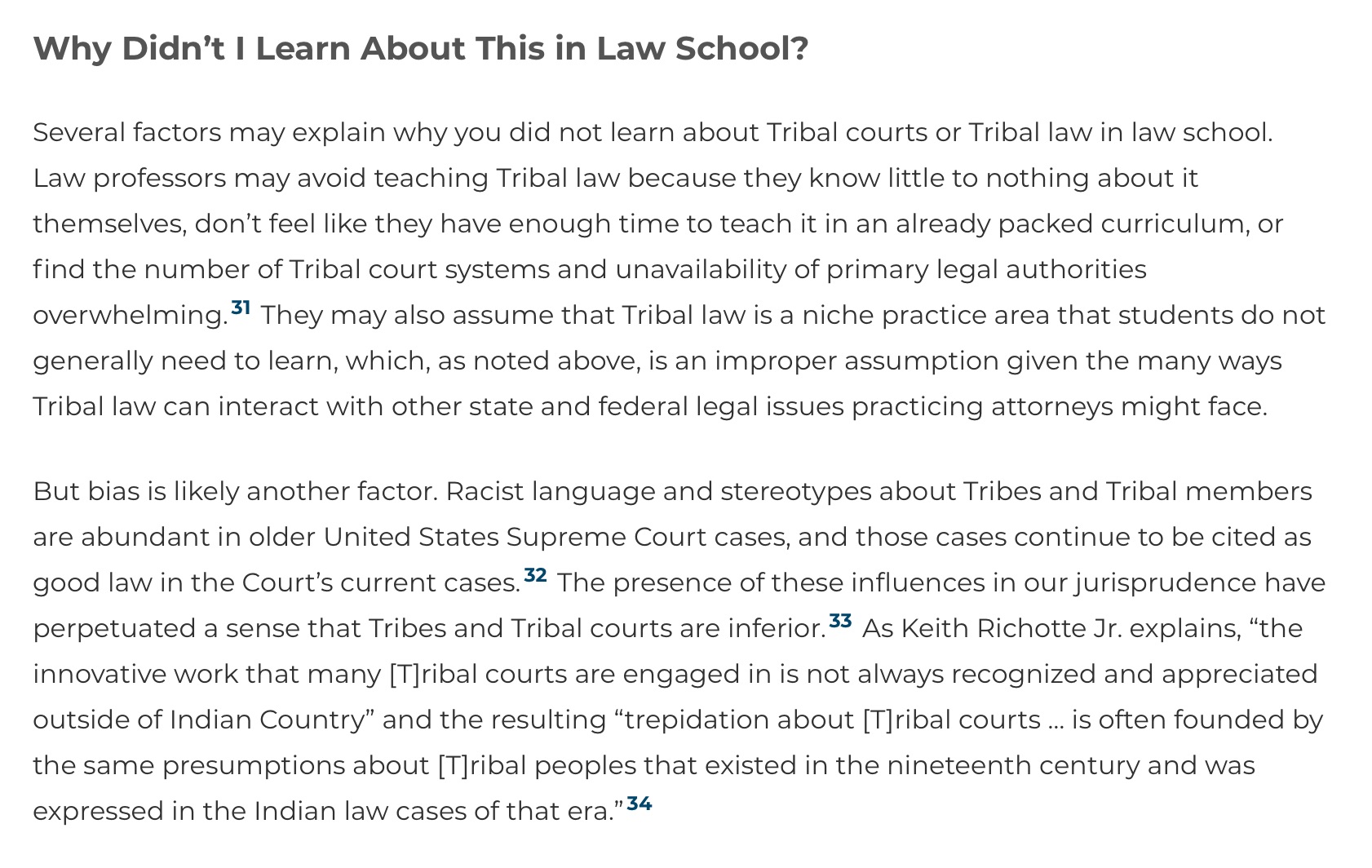

Amanda K. Stephen has published “Navigating Tribal Law Research” in the Washington State Bar Journal.

My favorite excerpt:

Here is the opinion in In the Matter of Lile.

Kekek Stark has posted “The Utmost Rights and Interests of the Indians: Tribal Law Interpretations of the Indian Civil Rights Act” on SSRN.

Highly recommended.

Here is the abstract:

It has been more than fifty years since Congress enacted the Indian Civil Right Act (hereinafter “ICRA”) and more than forty years since the United States Supreme Court in Martinez articulated that the tribal courts are the proper forum for the adjudication of ICRA claims. In the decades since, tribal courts have developed a rich body of intertribal common law pertaining to the implementation of the ICRA. This comes after over a century of assimilative policies in which the federal government attempted to eradicate native culture and traditions and subjected Indians to the deprivation of individual rights by federal and state judicial systems.So how are tribes doing in the implementation of the ICRA? Specifically, how are tribal courts balancing the promotion of tribal sovereignty with the protection of individual rights? Does the ICRA establish a mandate to tribal governments to assume and require judicial review of any allegedly illegal action by a tribal government? Can a Tribe accused of violating these primary rights also be the judge of its own actions and at same the time comply with federal law? This article will examine these questions in detail. In doing so, Part I provides a brief introduction. Part II details the implementation of individual rights protections prior to the enactment of the ICRA. Part III provides an overview of the passage of the ICRA. Part IV examines federal court encroachment into tribal court determinations of individual rights protections. Part V provides an overview of the ruling in Martinez. Part VI details tribal court interpretations of the ICRA associated with tribal sovereign immunity, tribal council actions, equal protection, due process, and criminal protections. Part VII concludes by offering recommendations for tribal courts in their ongoing review of the ICRA.

In the Detroit Legal News, here.

An excerpt:

Over 30 years ago in Michigan, then Supreme Court Chief Justice Michael Cavanagh began a relationship with our Tribal Courts. His initial words were prophetic to our neighbors: “We know we have more to learn from you than you do from us.” And so, it began. We have only scratched the surface of what we can learn. We can learn because there is a need, perhaps a necessity, that we open spaces and places for incorporating other world views and create procedures that nurture values that address areas of conflict in our communities.

The denied petitions are Lexington Ins. Co. v. Suquamish Tribe and Lexington Ins. Co. v. Mueller.

You must be logged in to post a comment.