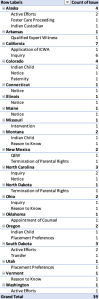

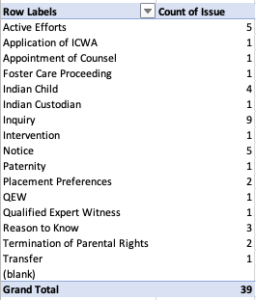

Colorado has long had a very low bar to trigger the reason to know provision of ICWA. The B.H. case from 2006 has long been a model for other states that involve the question of what information does a court need to trigger the “reason to know” requirement of 25 U.S.C. 1912(a). And here, in a recent CO Court of Appeals case, is what the current debate over how the regulations have changed the standards boils down to:

But an assertion of possible Indian heritage alone does not fall within a “reason to know” factor that would permit a participant or the court to assume the child is an “Indian child” under section 19-1-126(1)(a)(II). Thus, this type of an assertion does not require formal notice to a tribe or tribes to determine whether the child is an “Indian child.”

In re A-J.A.B., 2022 COA 31, P58

The state law referenced is the Colorado adoption of 25 C.F.R. 23.107(c), the regulations that are supposed to guide courts regarding the “reason to know” standard. However, this is a fundamentally different standard than that articulated by B.H.:

Because membership is peculiarly within the province of each Indian tribe, sufficiently reliable information of virtually any criteria upon which membership might be based must be considered adequate to trigger the notice provisions of the Act.

138 P.3d 299, 304

The court of appeals states that state law has changed enough that B.H.’s reasoning was done under a different standard than the one in effect today (ICWA, of course, has not changed).

Much like the discussion in the In re Z.J.G. case, we are again debating the points of the six factors the regulations articulate as giving a court reason to know, and how they (according to the CO Courts of Appeals) narrow the reason to know standard, rather than guide it.

We agree with the E.M. division that information about the child’s heritage does not constitute “reason to know” that the child is an Indian child under section 19-1-126(1)(a)(II)(A). Information about a possible affiliation with two tribal ancestral groups does not satisfy one of the six reason to know factors

2022 COA 31 at P71

It is honestly stunning to me (though it should not be), that the passage of federal regulations means we are all now re-litigating notice issues that had long been settled. Last week, the Colorado Court of Appeals held

We conclude that a parent’s assertion of Indian heritage, standing alone, is insufficient to trigger ICWA’s notice requirements but, rather, it invokes the petitioning party’s obligation to exercise

People in re J.L., 2022 COA 43, P3

due diligence under section 19-1-126(3). We further conclude that the exercise of due diligence under this provision is flexible and depends on the circumstances of, and the information presented to the court in, each case. Nonetheless, the record needs to show that the petitioning party earnestly endeavored to gather additional information that would assist the court in determining whether there is reason to know that the child is an Indian child.

And now, “due diligence” is an “earnest endeavor” on the part of the state when a parent tells the Court they have tribal relations. However, in both cases the court of appeals sent the case back due to the lack of “due diligence” to follow up on these statements by the parents. The Court in A-J.A.B. gives a very detailed remand instruction regarding due diligence, and what the Court will need by date certain.

To lower my blood pressure and end this post, I will remember what the Washington Supreme Court held, when faced with very similar facts and laws:

We hold that a court has a “reason to know” that a child is an Indian child when any participant in the proceeding indicates that the child has tribal heritage. We adopt this interpretation of the “reason to know” standard because it respects a tribe’s exclusive role in determining membership, comports with the canon of construction for interpreting statutes that deal with issues affecting Native people and tribes, is supported by the statutory language and implementing regulations, and serves the underlying purposes of ICWA and WICWA. Further, tribal membership eligibility varies widely from tribe to tribe, and tribes can, and do, change those requirements frequently. State courts cannot and should not attempt to determine tribal membership or eligibility. This is the province of each tribe, and we respect it.

In re Z.J.G., 471 P.3d 853, 865.

You must be logged in to post a comment.