Here is the opinion in United States v. Anderson.

Briefs:

Here are the relevant materials in United States v. Johnson (D. Minn.):

Here are the relevant materials in United States v. Brown (N.D. Okla.):

Here are the briefs in United States v. Gordon:

Ok, so there’s only that brief so far. Also, since the defendant stipulated to tribal membership with Nez Perce, I doubt this has legs, but it’s the kind of full-throated attack on the Indian status cases arising under the Indian country criminal jurisdiction statutes that we should expect more regularly — i.e., the kind that relies a LOT on single-authored concurrences and dissents from a certain SCT Justice that tends to rely on discredited historical research.

Here’s the lower court judgment (nothing terribly helpful here since the defendant stipulated to tribal membership):

Here is the opinion in United States v. Milk.

Briefs:

An excerpt from the opinion:

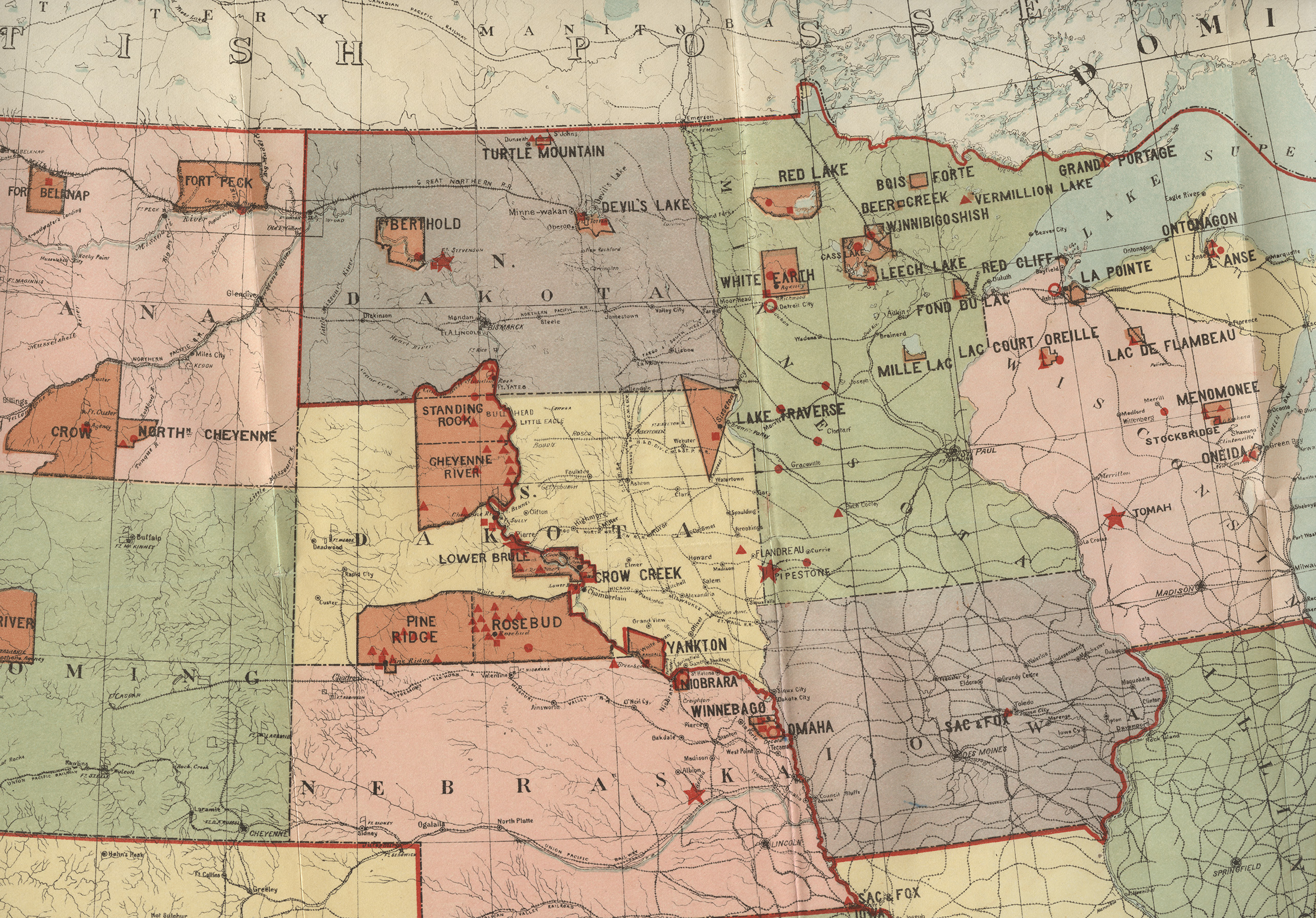

Milk, who is Native American and an enrolled member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, contends that the district court lacked jurisdiction because (1) he was convicted of crimes that are not enumerated under the Major Crimes Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1153,4 and (2) under the General Crimes Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1152, the alleged unlawful acts in this case occurred on the Pine Ridge Reservation and only involved American Indian people. But Milk’s arguments are foreclosed by precedent.

Here are materials in United States v. Buzzard (N.D. Okla.):

Here are the materials in United States v. English (D. Colo.):

33 Joint Memorandum in Support of Plea Agreement

36 Magistrate Minute Order: “This Court does not have jurisdiction over the charge in the proposed Plea Agreement. . . .”

An excerpt:

The Major Crimes Act represents one way in which Congress has permitted federal courts to exercise jurisdiction over crimes occurring on tribal lands which otherwise would be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the tribal courts. Now codified at 18 U.S.C. § 1153, the Act gives federal courts exclusive federal jurisdiction over certain enumerated felonies occurring between Indians in Indian Country, including, specifically, “a felony assault under section 113.” 18 U.S.C.A. § 1153(a). See also United States v. Burch, 169 F.3d 666, 669 (10th Cir. 1999). Prosecution of crimes not expressly designated in section 1153, including, specifically, simple assault – is reserved to the tribal courts, in recognition of their inherent sovereignty over such matters. United States v. Antelope, 430 U.S. 641, 643 n.1, 97 S.Ct. 1395, 1397 n.1, 51 L.Ed.2d 701 (1977); United States v. Quiver, 241 U.S. 602, 700-01, 36 S.Ct. 699, 605-06, 60 L.Ed. 1196 (1916); United States v. Burch, 169 F.3d 666, 668-69 (10thCir. 1999). See also United States v. Lara, 541 U.S. 193, 199, 124 S.Ct. 1628, 1632-33, 158 L.Ed.2d 420 (2004) (“[25 U.S.C. § 1301] says that it ‘recognize[s] and affirm[s]’ in each tribe the ‘inherent’ tribal power … to prosecute nonmember Indians for misdemeanors.”).

Here are materials in United States v. Jojola (D.N.M.):

Of course, if SCOTUS goes the wrong way in Brackeen, this case and hundreds will go much differently.

You must be logged in to post a comment.