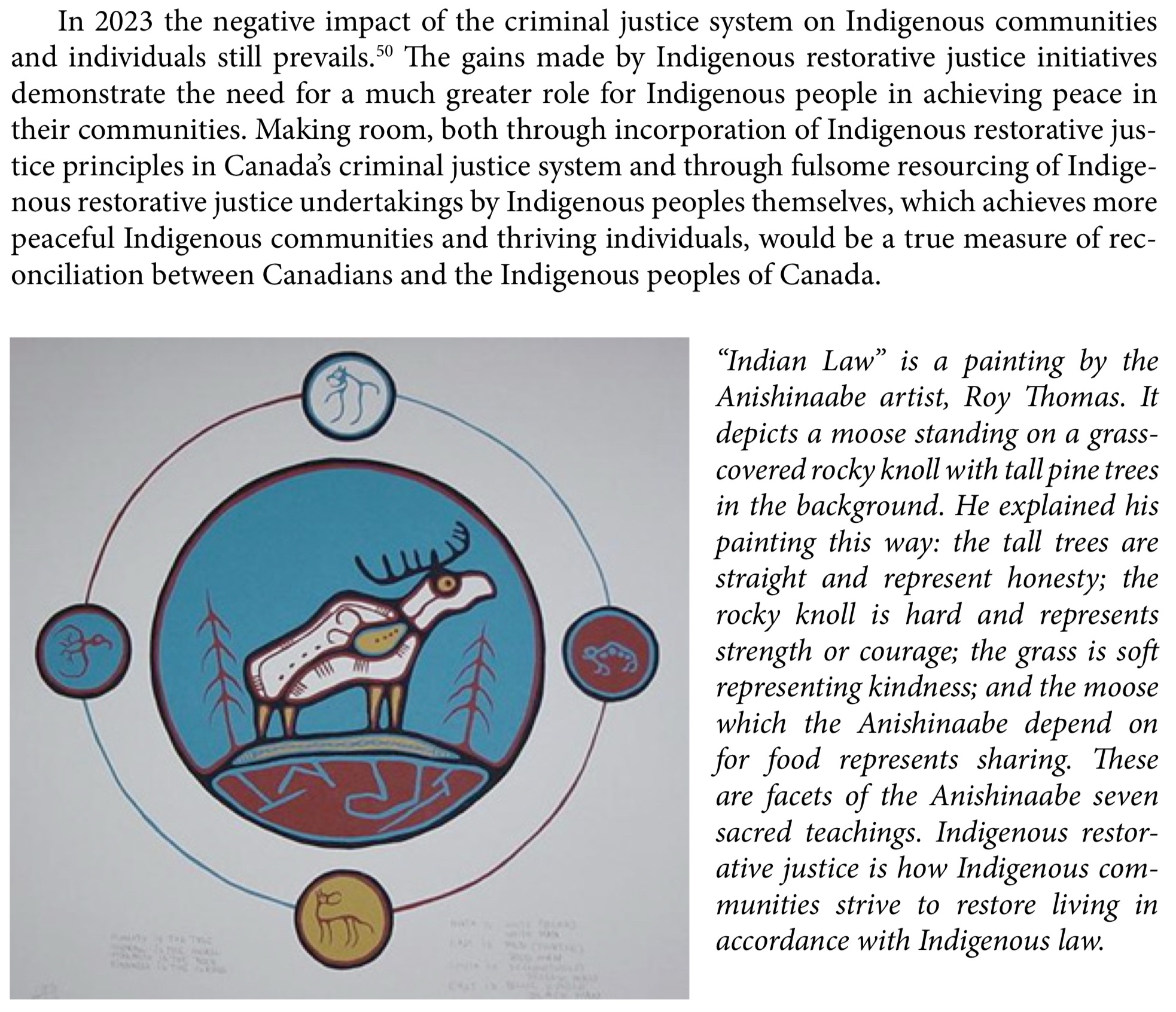

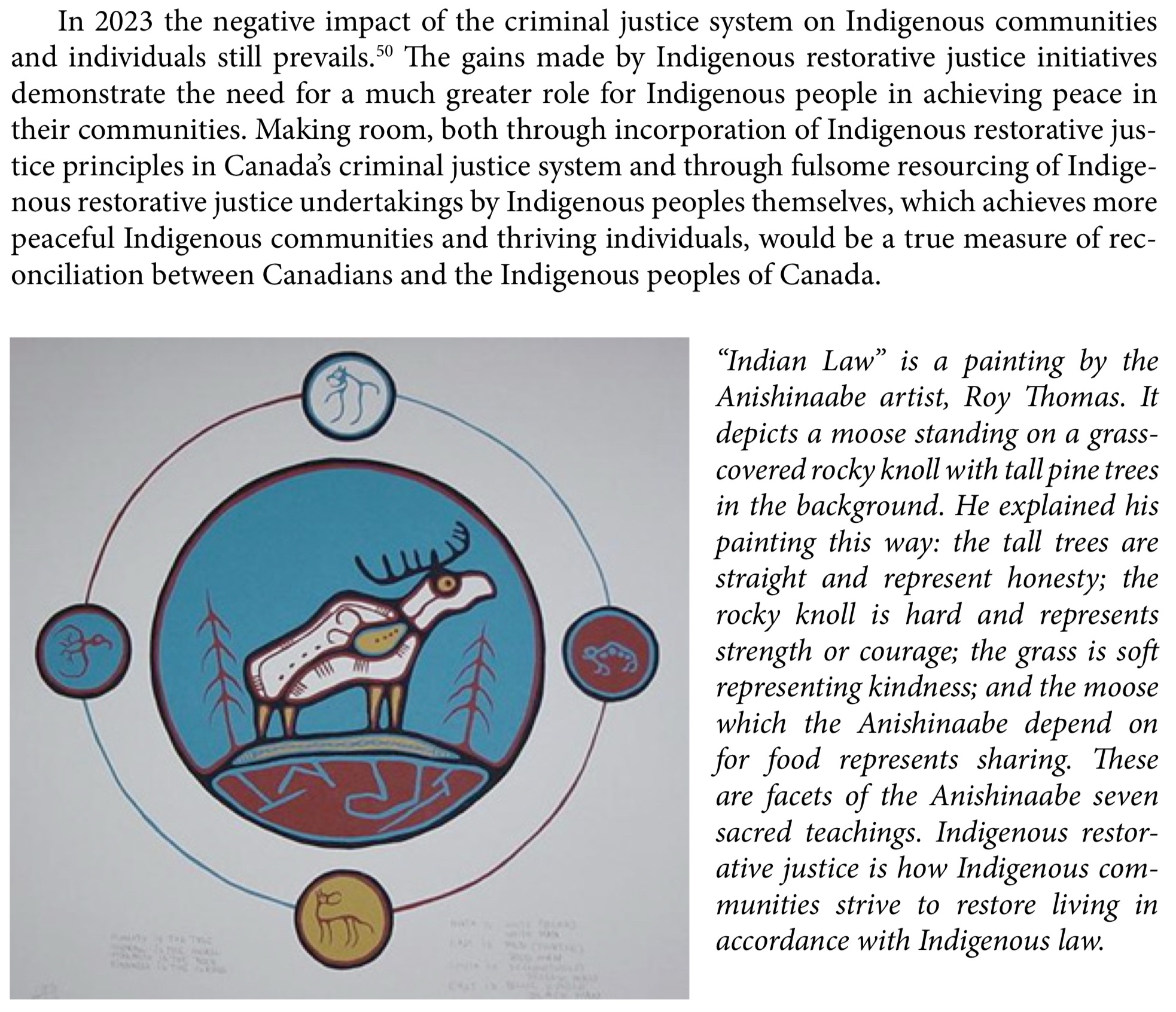

The Honourable Leonard S. Tony Mandamin has published “Emergence of Contemporary Indigenous Restorative Justice in Canada” in Constitution Forum constitutionnel.

Excerpt:

The Honourable Leonard S. Tony Mandamin has published “Emergence of Contemporary Indigenous Restorative Justice in Canada” in Constitution Forum constitutionnel.

Excerpt:

Ariana Kravetz has published “Rectifying Historical Wrongs: The Case for the Indigenous’ Inherent Right to Self–Govern Child Welfare in Canada” in the University of Miami Inter-American Law Review.

Aaron Mills has published “First Nations’ Citizenship and Kinship Compared: Belonging’s Stake in Legality” in the American Journal of Comparative Law.

Here is the abstract:

Many First Nation individuals appear to accept that debates about belonging to First Nations political community are properly framed as debates about citizenship. Interlocutors frequently identify the ongoing significance of kinship, but fold it into their conception of citizenship. This Article resists citizenship’s orthodoxy. Kinship is not a unique feature of First Nations citizenship, but rather is its own model of belonging to a political community: a model internal to First Nations law, understood on its own terms. There are, then, two models of belonging to First Nations political community, citizenship and kinship, within and over which debates about belonging play out.

For First Nations political communities using their own systems of law, kinship is a source of fundamental legal interests, just as citizenship is a source of fundamental rights and freedoms in modern liberal democracies. However, comparativists, legal theorists, and political theorists have struggled to appreciate this reality because internal (or settler) colonialism disconnects kinship from legality conceptually and thus institutionally. Those connections must be reestablished.

To that end, this Article shows that, functionally, kinship is a full answer to citizenship. The argument is made in two interwoven parts, each of which turns on the picture of kinship as a structural feature of First Nations law, understood on its own terms. First, kinship is citizenship’s political equal insofar as it offers a justificatory account of belonging to a political community; second, kinship is citizenship’s legal equal insofar as it, too, serves as a foundation for fundamental legal interests. The gravamen of this Article is, thus, twofold. First, one is not hearing what First Nations law says about belonging if one is only willing or able to listen in the language of citizenship. Second, the stakes in one’s choice of model are significant: citizenship and kinship structure legality in fundamentally different ways.

From The Nishnawbe News [Northern Michigan University], May 1972:

Here is the document titled “CMA Apology to Indigenous Peoples: Historical and Ethical Review Report:

Alyssa Couchie has published “ReBraiding Frayed Sweetgrass for Niijaansinaanik: Understanding Canadian Indigenous Child Welfare Issues as International Atrocity Crimes” in the Michigan Journal of International Law.

Here is the abstract:

The unearthing of the remains of Indigenous children on the sites of former Indian Residential Schools (“IRS”) in Canada has focused greater attention on anti-Indigenous atrocity violence in the country. While such increased attention, combined with recent efforts at redressing associated harms, represents a step forward in terms of recognizing and addressing the harms caused to Indigenous peoples through the settler-colonial process in Canada, this note expresses concern that the dominant framings of anti-Indigenous atrocity violence remain myopically focused on an overly narrow subset of harms and forms of violence, especially those committed at IRSs. It does so by utilizing a process-based understanding of atrocity and genocide that helps draw connections between familiar, highly visible, and less recognized forms of atrocity violence, which tend to be overlapping and mutually reinforcing in terms of their destructive effects. This process-based understanding challenges the neocolonial, racist, and discriminatory attitudes reflected in the drafting and interpretation of the Genocide Convention and other atrocity laws that ignore the lived experiences of subjugated groups. Utilizing this approach, this note argues that, as applied to Indigenous populations, Canada’s longstanding discriminatory child welfare practices and policies represent an overlooked process of anti-Indigenous atrocity violence. Only by understanding current child welfare challenges facing Indigenous communities as interwoven with longstanding anti-Indigenous atrocity processes, such as the IRS system, can we understand what is at stake for affected communities and fashion appropriate remedies in international and domestic law.

Kalae Trask has published “Toward Mutual Recognition: An Investigation of Oral Tradition Evidence in the United States and Canada” in the Washington Journal of Social and Environmental Justice.

The abstract:

United States (“U.S.”) courts have long failed to recognize the value of oral traditional evidence (“OTE”) in the law. Yet, for Indigenous peoples, OTE forms the basis of many of their claims to place, property, and political power. In Canada, courts must examine Indigenous OTE on “equal footing” with other forms of admissible evidence. While legal scholars have suggested applying Canadian precedent to U.S. law regarding OTE, scholarship has generally failed to critically examine the underlying ethos of settler courts as a barrier to OTE admission and usefulness. This essay uses the work of political philosopher, James Tully, to examine OTE not just as evidence, but as an exercise of Indigenous self-determination. By recognizing the inherent political nature of OTE, U.S. courts may expand on Canadian law to build a “just relationship” with Indigenous peoples.

NY Times Coverage here

The Canadian government announced Tuesday that it had reached what it called the largest settlement in Canada’s history, paying $31.5 billion to fix the nation’s discriminatory child welfare system and compensate the Indigenous people harmed by it.

Agreement in principle/press release here

For those who were following this case, it involves the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, which is led by Cindy Blackstock. The settlement attempts to reform Child and Family Services and address Jordan’s Principle. This is a major settlement and significant milestone for Native children and families in Canada.

Here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.