Colorado is the most recent state to add a pro hac rule for ICWA cases. This rule is pretty narrow, and only applies for attorneys representing tribes where the tribe has moved to intervene in the case on behalf of their child. This would not apply to any attorneys representing individuals (like a grandma or auntie) in an ICWA case, nor to any appellate work on behalf of tribes filing amicus briefs. However, the rule only requires a verified motion to avoid both fees and local association, which is great for tribal attorneys.

ICWA

Indian Child’s Tribe Determination out of Alaska Supreme Court

Here is the decision. sp7628

The facts of this case were a little unusual, where a foster family attempted to have a child in their care made a member of one tribe when he was already a citizen of another. The holdings, however, are useful both for clarity in the regulations for the determination of an Indian child’s tribe, and for keeping state courts out of tribal citizenship decisions.

Court decisions reflect the same rule of deference to the tribe’s exercise of control over its own membership. The U.S. Supreme Court has long recognized tribes’ “inherent power to determine tribal membership.” In John v. Baker we recognized that “the Supreme Court has articulated a core set of [tribes’] sovereign powers that remain intact [unless federal law provides otherwise]; in particular, internal functions involving tribal membership and domestic affairs lie within a tribe’s retained inherent sovereign powers.” We have also “long recognized that sovereign powers exist unless divested,” and “ ‘the principle that Indian tribes are sovereign, self-governing entities’ governs ‘all cases where essential tribal relations or rights of Indians are involved.’ ”

Chignik Lagoon’s argument would require state courts to independently interpret tribal constitutions and other sources of law and substitute their own judgment on questions of tribal membership. This argument is directly contrary to the directive of 25 C.F.R. § 23.108.

The Indian Law Clinic at MSU College of Law provided research and technical assistance to the Village of Wales in this case.

Greg Ablavsky Responds to Rob Natelson’s “Cite Check” of Ablavsky’s “Beyond the Indian Commerce Clause”

Gregory Ablavsky’s “Beyond the Indian Commerce Clause: Robert Natelson’s Problematic ‘Cite-Check’” is at the Stanford Law School blog, Legal Aggregate.

An excerpt:

Here’s that context: In 2007, Mr. Natelson wrote a law review article on the original understanding of the Indian Commerce Clause. Justice Thomas later cited Mr. Natelson’s article in a 2013 concurrence questioning Congress’s authority to enact the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA). In 2015, while a graduate student finishing my J.D./Ph.D. in American Legal History at Penn, I published Beyond the Indian Commerce Clause in the YLJ, which revisited original understandings of the sources of federal power over Indian affairs. In the article, I argued that the Founders thought that the federal government’s authority rested not just on the Indian Commerce Clause but on the interplay between multipleconstitutional provisions, including the Treaty Clause, the Territory Clause, the war powers, the law of nations, and the Constitution’s limits on state authority. The article also challenged Justice Thomas’s and Mr. Natelson’s conclusions in what Mr. Natelson later conceded was a “generally respectful” tone. Since the article, a number of subsequent articles by other scholars, some right-of-center and others disagreeing with my conclusions, have similarly challenged Mr. Natelson’s views.

Recommended reading. Professor Ablavsky is the leading legal historian of federal Indian law right now and filed a compelling amicus brief in Brackeen (here).

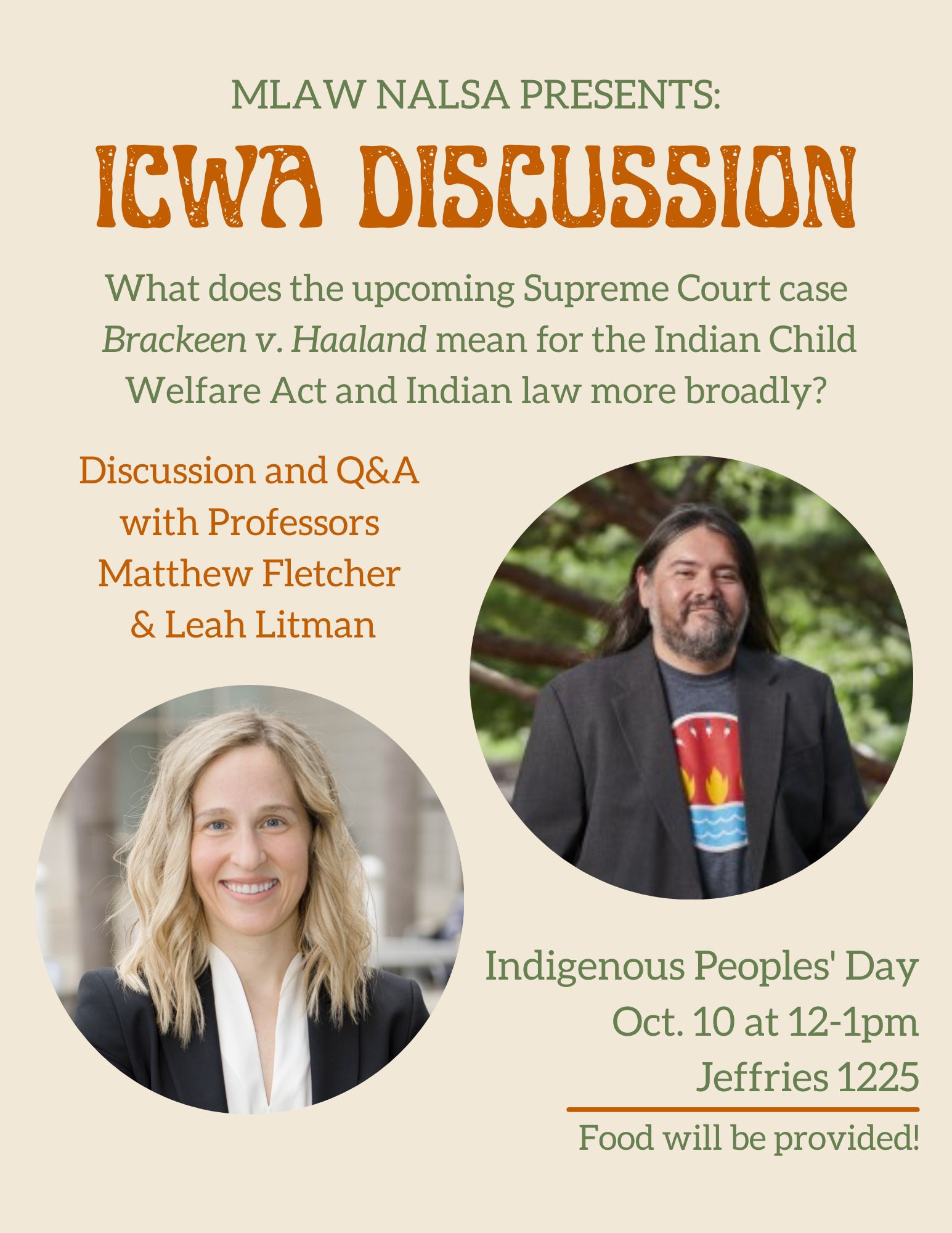

UM NALSA Talk on Brackeen with Leah Litman and Fletcher Today @ Noon

Comic here.

Penn Law/Field Center Session on the Origins and History of the Indian Child Welfare Act

Here:

Next session is December 1:

Briefing Completed in Haaland v. Brackeen [ICWA]

With the reply briefs filed yesterday, all of the briefing is completed in the Supreme Court case Haaland v. Brackeen. Oral argument will be at the Court on November 9th. There will be a decision before the end of June, 2023, though there’s no good way to determine when that will arrive other than that.

Colorado Supreme Court On Inquiry and Notice

Unfortunately the Colorado Court did not continue its strong position on notice they had in the 2006 ex rel B.H. case.

Thus, as the divisions in A-J.A.B. and Jay.J.L. aptly noted, B.H. “required notice to tribes under a different criterion than the one in effect today.” A-J.A.B., ¶ 76, 511 P.3d at 763; Jay.J.L., ¶ 32, 514 P.3d at 319. As such, B.H. is inapposite.

¶56 In short, while assertions of a child’s Indian heritage gave a juvenile court “reason to believe” that the child was an Indian child under Colorado law in 2006, see B.H., 138 P.3d at 303–04 (emphasis added), the question we confront in this case is whether such assertions give a juvenile court “reason to know” that the child is an Indian child under Colorado law in 2022, § 19-1-126(1)(b) (emphasis added). We agree with the divisions in A-J.A.B. and Jay.J.L. that mere assertions of a child’s Indian heritage (including those that specify a tribe or multiple tribes by name), without more, are not enough to give a juvenile court reason to know that the child is an Indian child. And, correspondingly, to the extent that other divisions of the court of appeals have expressly or impliedly reached a contrary conclusion, we overrule those decisions.

The Indian Law Clinic at MSU represented the tribal amici in this case, the Ute Mountain Ute and Southern Ute Indian Tribes.

Washington Court of Appeals on Standard of Proof at Initial Removal

We also conclude that when the Department has reason to believe that a child is an Indian child under ICWA and WICWA, the heightened removal standard in those statutes applies to ex parte pick-up order requests. Because the Department had reason to know A.W. is an Indian child–information not shared with the trial court–and the trial court appliced an incorrect legal standard in assessing the Department’s evidence at that stage of the proceeding, the trial court erred in not vacating the pick up order.

Active Efforts Case out of the Colorado Supreme Court

I did not realize how far behind I was on these. Here is a case from the end of June on active efforts from the Colorado Supreme Court.

To be honest, this case holding is one that most, if not all, states have come to agreement on either in case law, state law, or state policy.

The court concludes that ICWA’s “active efforts” is a heightened standard requiring a greater degree of engagement by agencies like DHS with Native American families compared to the traditional “reasonable efforts” standard.

Qualified Expert Witness Opinion from the Alaska Supreme Court

The question of qualified expert witness (QEW) has confounded the Alaska Court for years, and unfortunately the regulations and guidelines didn’t provide quite as much clarification as they needed. That said, this decision seems to chart a new course for the Alaska Supreme Court:

As explained further below, the superior court’s interpretation of Oliver N. was mistaken. An expert on tribal cultural practices need not testify about the causal connection between the parent’s conduct and serious damage to the child so long as there is testimony by an additional expert qualified to testify about the causal connection.

* * *

In both cases there is reason to believe cultural assumptions informed the evidence presented to some degree. Had the cultural experts had a chance to review the record — particularly the other expert testimony — they may have been able to respond to and contextualize it. For instance, Dr. Cranor emphasized attachment theory and the economic situation of the families in both cases — areas that may implicate cultural mores or biases. If the cultural experts were aware of this testimony, they could haven addressed attachment theory, economic interdependence, and housing practices in the context of prevailing tribal standards.

You must be logged in to post a comment.