Prior post here.

Agenda here. Most posts as the day progresses.

For those committed to increasing diversity in the legal profession, Texas A&M University School of Law announces the Accountability, Climate, Equity, and Scholarship (ACES) Fellows Program at Texas A&M University School of Law.

The ACES program is a two-year fellowship designed to help early career legal scholars get the training and mentoring necessary to become successful members of the legal academy. Funded by Texas A&M’s Office of the Provost and administered by the University’s Office for Diversity, the fellowship is designed to help early career scholars who are strongly committed to diversity.

The position has a light teaching load (one class per year) to enable the Fellow to focus on advancing their research agenda, scholarship (including at least one published article), and other necessary skills in anticipation of seeking a tenure-track, faculty position on the law school teaching market. Faculty are committed to providing the mentoring necessary to help the Fellow to succeed on the legal academic job market and in the legal academy.

Details:

–24-month term, starting between July 1- August 10, 2022.

–Teach one class per year

–$60,000 annual salary plus benefits

–$4,500 annual travel and development fund

–Reimbursement of moving expenses

–Eligibility: Must have earned JD or PhD degree between January 1, 2012 and July 1, 2022

Thomas Mitchell, Brendan Maher, and Huyen Pham are on the appointments committee for this fellowship. Please feel free to reach out to any of them with questions.

Here:

Alaska Native Corporation Endowment Models

Robert Snigaroff & Craig Richards

PDF

New settlement trust provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 have significant implications for Alaska Native Corporation (ANC) business longevity and the appropriateness of an operating business model given ANC goals as stated in their missions. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) authorized the creation of for-profit corporations for the benefit of Alaska Native shareholders. But for Alaska Natives, cultural continuation was and continues to be a desired goal. Considering the typical life span of U.S. corporations and the inevitability of eventual failure, the for-profit corporate model is inconsistent with aspects of the ANC mission. Settlement trust amendments to ANCSA facilitate ANC cultural continuation goals solving the problem of business viability risk. We make a normative case that ANCs should consider increasing endowment business activity. We also discuss the Alaska Permanent Fund and lessons that those structuring settlement trusts might learn from literature on sovereign wealth funds and endowments.

Alaska’s Tribal Trust Lands: A Forgotten History

Kyle E. Scherer

PDF

Since the enactment of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971, there has been significant debate over whether the Secretary of the Interior should accept land in trust for the benefit of federally recognized tribes in Alaska. A number of legal opinions have considered the issue and have reached starkly different conclusions. In 2017, the United States accepted in trust a small parcel of land in Craig, Alaska. This affirmative decision drew strong reactions from both sides of the argument. Notably absent from the conversation, however, was any mention or discussion of Alaska’s existing trust parcels. Hidden in plain sight, their stories reflect the complicated history of federal Indian policy in Alaska, and inform the debate over the consequences of any future acquisitions.

Selective Justice: A Crisis of Missing and Murdered Alaska Native Women

Megan Mallonee

PDF

Across the country, Indigenous women are murdered more than any other population and go missing at disproportionate rates. This crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women is amplified in Alaska, where the vast landscape, a confusing jurisdictional scheme, and a history of systemic racism all create significant barriers to justice for Alaska Native women. This Note examines the roots of the crisis and calls for a holistic response that acknowledges the role of colonialism, Indigenous genocide, and governmental failures. While this Note focuses on the epidemic of violence against Alaska Native women in particular, it seeks to provide solutions that will increase the visibility and protection of Indigenous women throughout North America.

“If a person is murdered in the village, you’ll be lucky if someone comes in three, four days to work the murder site and gather what needs to be gathered so you can figure out a case later . . . but if you shoot a moose out of season, you’re going to get two brownshirts there that day.”

Here.

Abstract:

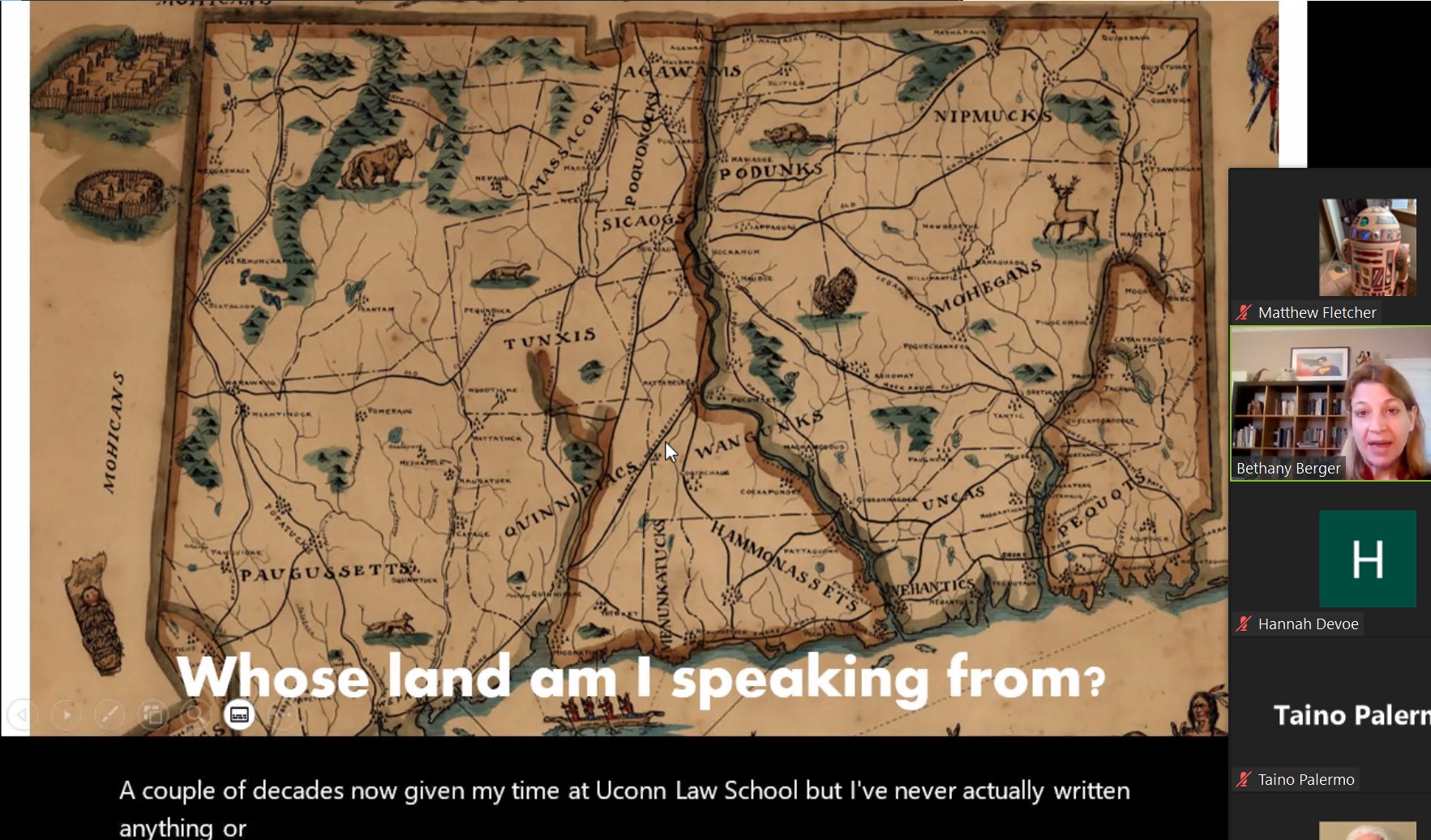

There are less than three dozen American Indians who are enrolled tribal members who are tenure system law professors in American law schools. We study this group, as well as a few known tribal members who have either retired or left the academy for loftier pursuits, for purposes of identifying the profiles of tribally enrolled American Indians on the tenure track in American law schools. The object of this short paper is to advise American Indian law students and others on how to become an American Indian law professor. This paper is an update from a 2012 paper: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2058557.

Prepared in anticipation of the “Transforming the Legal Academy” conference.

Trevor Reed has posted “Creative Sovereignties: Should Copyright Apply on Tribal Lands?,” forthcoming in the Journal of the Copyright Society, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

The federal Copyright Act grants authors the exclusive right to use their original creative expressions in certain ways. At the same time, the Act pre-empts most equivalent rights to creative expressions established by States. However, the Copyright Act is silent as to its applicability on the lands of Native American Tribes and its preemptive effect on rights sovereign Tribal governments accord to creativity. With Tribes and Tribal members increasingly engaged in the global creative economy and in litigation to defend their intellectual properties, the status of the Copyright Act on Tribal lands has become a critical issue that Congress or the courts must now address.

The stakes of applying the Copyright Act on Tribal lands may be quite high for Tribes. Drawing on doctrinal research coupled with community-partnered ethnographic research conducted with the Hopi Tribe, I explain how federal copyright law impacts contemporary tribal sovereignty. Copyright clearly supports certain forms of Tribal creativity intended for off-reservation markets. But for locally circulating creativity — including forms of cultural or ceremonial creativity that help maintain Tribal identity, social relations, and traditional sources of authority — applying Copyright may very well disrupt the exercise of Tribal sovereignty and cause substantial harm to Tribal creative economies.

Based on this research, I argue that the Copyright Act should apply on Tribal lands, but only to the extent permitted by each Tribe. Where Tribal intellectual property laws, protocols, or customary laws occupy the same field as the Copyright Act, Tribal entitlements and remedies, not federal ones, should govern creativity occurring on Tribal lands, with federal copyright law providing enforcement of Tribal intellectual property rights beyond a Tribe’s borders. Otherwise, the unilateral imposition of the Copyright Act on tribal creativity, to the exclusion of Tribal laws, impermissibly invades Tribal sovereignty as articulated in both current federal policy and the international norms enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Nathan Frischkorn has posted “Treaty Rights and Water Habitat: Applying the United States v. Washington Culverts Decision to Anishinaabe Akiing,” forthcoming in the Arizona Journal of Environmental Law & Policy, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

In 2017, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that culverts installed by the state of Washington which reduce the habitat of treaty-protected salmon violate the treaty rights of Tribes in western Washington. That decision—part of the long-running United States v. Washington litigation—has since become known as the “Culverts Case.” Broadly, that decision essentially holds that habitat protection is a component of treaty-protected rights to hunt, fish, and gather. This Article analyzes what habitat protection as a treaty right would mean for the water-based, treaty-protected resources—such as fish and manoomin (wild rice)—of the Anishinaabe Tribes in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. This Article describes relevant treaties to determine what water-based resources those Tribes have treaty rights to, and analyzes relevant precedent that defines or limits the exercise or scope of those rights in state and federal courts. Through interviews with individuals who work with Tribes on issues pertaining to usufructuary rights, this Article identifies specific environmental threats to water-based treaty resources throughout the Great Lakes region. By analogizing those identified threats to the culverts at issue in United States v. Washington, this Article examines what habitat protection as a treaty right would mean in Anishinaabe Akiing.

Dylan R. Hedden-Nicely and Stacy L. Leeds have published “A Familiar Crossroads: McGirt v. Oklahoma and the Future of Federal Indian Law Canon” in the New Mexico Law Review.

Highly recommended!

Here:

Introduction

Mary Kathryn Nagle

The Past May Be Prologue, But It Does Not Dictate Our Future: This Is the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s Table

Jonodev Chaudhuri

Reflections on McGirt v. Oklahoma: A Case Team Perspective

Riyaz Kanji, David Giampetroni, and Philip Tinker

The Indian Treaty Canon and McGirt v. Oklahoma: Righting the Ship

Lauren King

A Wealth of Sovereign Choices: Tax Implications of McGirt v. Oklahoma and the Promise of Tribal Economic Development

Stacy Leeds and Lonnie Beard

The Sky Will Not Fall in Oklahoma

Clint Summers

A Coherent Ethic of Lawyering in Post-McGirt Oklahoma

Julie Combs

Reclaiming Our Reservation: Mvskoke Tvstvnvke Hoktvke Tuccenet (Etem) Opunayakes

Sarah Deer

You must be logged in to post a comment.