Here is the order in Tarabochia v. Quinault Indian Nation:

Here is the order in Tarabochia v. Quinault Indian Nation:

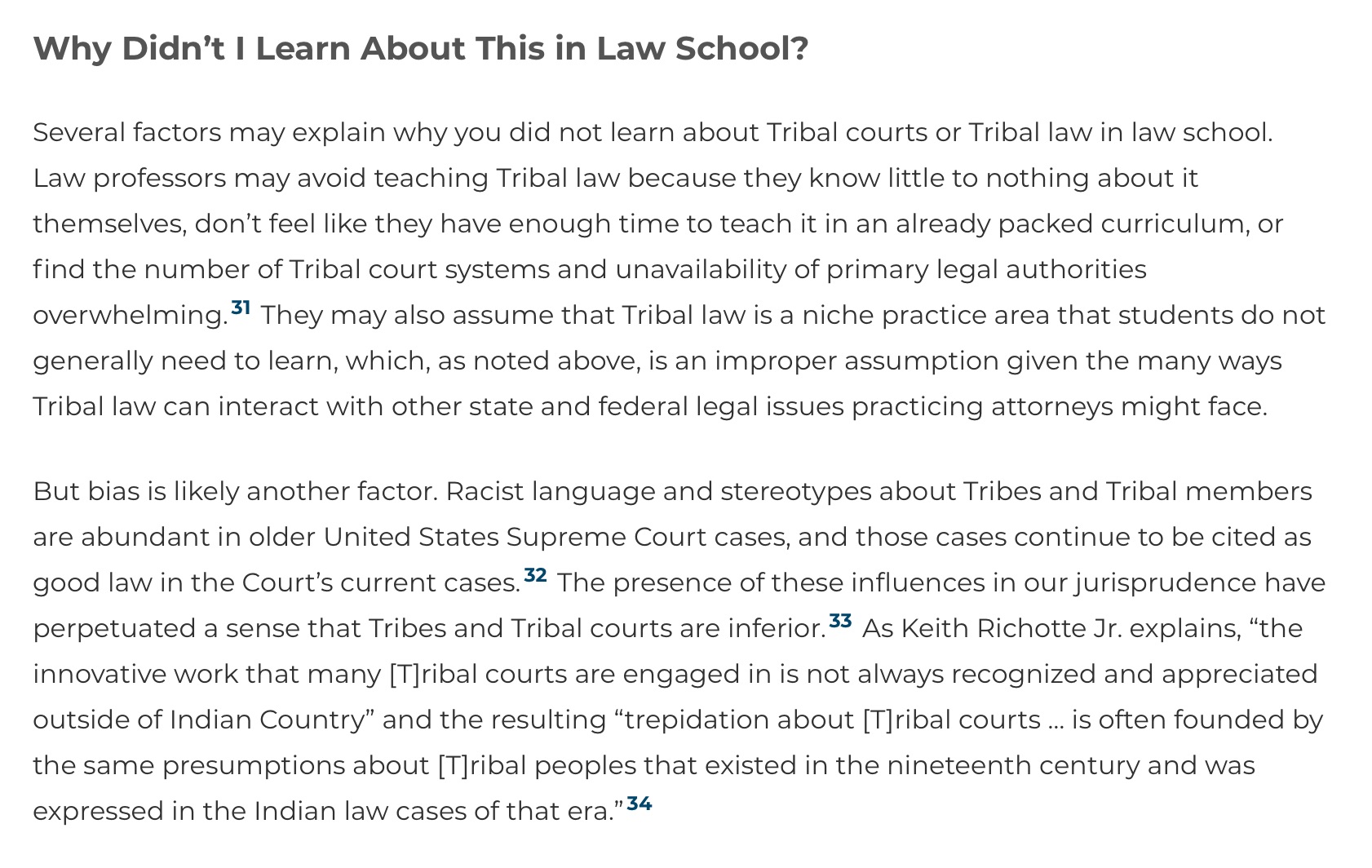

Amanda K. Stephen has published “Navigating Tribal Law Research” in the Washington State Bar Journal.

My favorite excerpt:

Carla D. Pratt has published “Indianness as Property” in the B.U. Law Review.

Abstract:

This Article expands upon the seminal work by Cheryl Harris entitled Whiteness as Property by exploring the intersection of race and property through Indianness. Indianness has been constructed as a form of property

conferring rights and privileges to its holders which this Article examines through the inertial relationship between race and legal status. Tracing the historical evolution of Indianness from the slavery era to the modern era demonstrates the complex relationship between tribal sovereignty, citizenship and Indian identity. This legal history contextualizes contemporary disputes over who can enjoy tribal citizenship and be Indian. This Article advocates for a reevaluation of Indianness that it is not grounded in notions of race and property, but rather sovereignty, history and culture, asserting that broadening the conception of Indianness will strengthen tribal sovereignty.

There are three responses (one forthcoming) to this paper:

Rejecting the Racialization of Indianness

Andrea J. Martin

Nanaboozhoo and Derrick Bell Go for a Walk

Matthew L.M. Fletcher

Here.

Abstract:

For too long, tribal judiciaries have been an afterthought in the story of tribal self-determination. Until the last half-century, many tribal nations relied on federally administered courts or had no court systems at all. As tribal nations continue to develop their law-enforcement and police powers, tribal justice systems now play a critical role in tribal self-determination. But because tribal codes and constitutions tend to borrow extensively from federal and state law, tribal judges find themselves forced to apply and enforce laws that are poor cultural fits for Indian communities—an unfortunate reality that hampers tribal judges’ ability to regulate and improve tribal governance.

Even where tribal legislatures leave room for tribal judges to apply tribal customary law, the results are haphazard at best. This Article surveys a sample of tribal-court decisions that have used customary law to regulate tribal governance. Tribal judges have interpreted customary law when it is expressly incorporated into tribal positive law, they have looked to customary law to provide substantive rules of decision, and they have relied on customary law as an interpretive tool. Reliance on customary law is ascendant, but still rare, in tribal courts.

Recognizing that Indian country will continue to rely on borrowed laws, and aiming to empower tribal courts to advance tribal governance, this Article proposes that tribal judges adopt an Indigenous canon of construction of tribal laws. Elevating a thirty-year-old taxonomy first articulated by Chief Justice Irvin in Stepetin v. Nisqually Indian Community, this Article recommends that tribal judges seek out and apply tribal customary law in cases where (1) the relevant doctrine arose in federal or state statutes or common law; (2) the tribal nation has not explicitly adopted federal or state law on a given issue in writing; (3) written tribal law was adopted or shifted as a result of the colonizer’s pressure and interests; and (4) tribal custom is inconsistent with the written tribal law, most especially if the law violates the relational philosophies of that tribal nation. Tribal judiciaries experienced at applying tribal customary law will be better positioned to do justice in Indian country.

Kekek Jason Stark has published “Exercising the Right of Self-Rule: Tribal Constitutions and Tribal Customary Law” in the Mitchell Hamline Law Review. PDF

Here is an excerpt:

In the context of the development and implementation of Tribal constitutions, Tribal Nations must ask themselves whether the federal government was playing a trick on Tribal Nations by imposing the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) and its corresponding constitutions and Anglo-American governing principles upon Indian country. Are these documents and corresponding governing principles actually “shit,” dressed up as “smart berries” under the guise of making Tribal Nations “wise” in the image of Anglo-American law? Ninety years after the enactment of the IRA, it is time Tribal Nations become wise and return to traditional constitutional principles based on Tribal customary law and unwritten, ancient Tribal constitutions.

As always with KJS, highly recommended.

Crispin South has posted “Transplanted Rights in the Choctaw Nation: Threats to Sovereignty and Potential Solutions,” forthcoming in the Texas Journal on Civil Liberties & Civil Rights, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

The constitutions of Federally Recognized Indian Tribes are varied, but nearly all contain a bill of rights. The Choctaw Nation’s Constitution, like that of several other Tribes, rather than specifically enumerating rights, instead contains a single catch-all provision, protecting the same rights available to citizens of the State of Oklahoma. Recently, the Choctaw Nation’s Constitutional Court adopted a broad interpretation of this provision, potentially allowing non-Tribal sovereigns, like the State of Oklahoma, to indirectly control the laws and public policy of the Tribe. This is a serious threat to the Tribe’s sovereignty, touching on issues of transplanted law raised by Indian Law scholars Elmer Rusco and Wenona Singel. To address this threat, the Choctaw Nation, and other Tribal Nations with similar constitutional provisions, ought to adopt a practice of selectively incorporating rights. Under this approach, only those rights fundamental to the Tribal structure of liberty and democracy would be incorporated, thus preserving the Tribe’s right to be different from the State, and the United States. Little has been written regarding these “transplanted rights” provisions in Tribal constitutions, and nearly nothing has been published proposing judicial and legislative solutions to the problems raised by these provisions. This note fills this gap in the literature by proposing judicially focused solutions, legislative solutions, and solutions involving constitutional reform.

Here is the opinion in Payment v. Election Commission:

Here is the opinion in McRorie v. Election Commission:

Here are the materials in the case captioned California Valley Miwok Tribe v. Haaland (D.D.C.):

37 Motion for Preliminary Injunction

You must be logged in to post a comment.