Sam Carter and Robin Rotman have posted “Resurfacing Sovereignty: Who Regulates Surface Mining In Indian Country After McGirt?,” forthcoming in the Montana Law Review, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

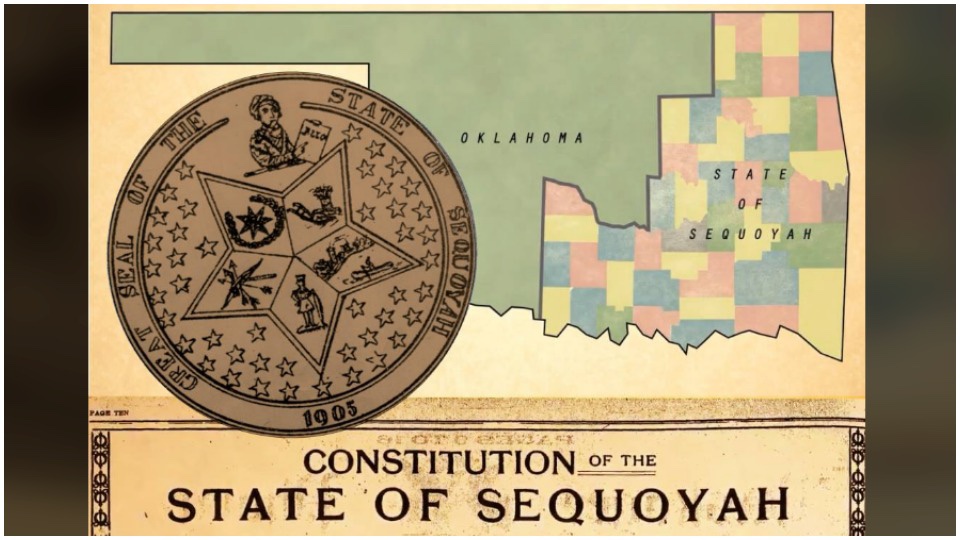

Following the decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma, 140 S. Ct. 2452 (2020), there has been a surge of litigation from the State of Oklahoma seeking to clarify the scope of the McGirt holding. While the Supreme Court of the United States was clear that the holding in McGirt was limited to criminal jurisdiction under the Major Crimes Act, it has sparked subsequent litigation regarding the scope of tribal authority. The pending case of State of Oklahoma v. United States Department of the Interior, which concerns surface mining regulation in Indian Country in Oklahoma, will test the application of McGirt outside of the criminal context. To this end, our article makes three recommendations: (1) in litigation concerning tribal lands, tribes should be a necessary party for litigation to proceed; (2) Congress should invest in pathways for tribes to build the capacity to create and manage their own programs, and (3) when tribal self-determination is encouraged and jurisdictional boundaries are clear, tribes can retain agency over their energy future and are less susceptible to the social harms that have been associated with the development of energy projects.

You must be logged in to post a comment.