Here:

Lower court materials here.

Colorado has long had a very low bar to trigger the reason to know provision of ICWA. The B.H. case from 2006 has long been a model for other states that involve the question of what information does a court need to trigger the “reason to know” requirement of 25 U.S.C. 1912(a). And here, in a recent CO Court of Appeals case, is what the current debate over how the regulations have changed the standards boils down to:

But an assertion of possible Indian heritage alone does not fall within a “reason to know” factor that would permit a participant or the court to assume the child is an “Indian child” under section 19-1-126(1)(a)(II). Thus, this type of an assertion does not require formal notice to a tribe or tribes to determine whether the child is an “Indian child.”

In re A-J.A.B., 2022 COA 31, P58

The state law referenced is the Colorado adoption of 25 C.F.R. 23.107(c), the regulations that are supposed to guide courts regarding the “reason to know” standard. However, this is a fundamentally different standard than that articulated by B.H.:

Because membership is peculiarly within the province of each Indian tribe, sufficiently reliable information of virtually any criteria upon which membership might be based must be considered adequate to trigger the notice provisions of the Act.

138 P.3d 299, 304

The court of appeals states that state law has changed enough that B.H.’s reasoning was done under a different standard than the one in effect today (ICWA, of course, has not changed).

Much like the discussion in the In re Z.J.G. case, we are again debating the points of the six factors the regulations articulate as giving a court reason to know, and how they (according to the CO Courts of Appeals) narrow the reason to know standard, rather than guide it.

We agree with the E.M. division that information about the child’s heritage does not constitute “reason to know” that the child is an Indian child under section 19-1-126(1)(a)(II)(A). Information about a possible affiliation with two tribal ancestral groups does not satisfy one of the six reason to know factors

2022 COA 31 at P71

It is honestly stunning to me (though it should not be), that the passage of federal regulations means we are all now re-litigating notice issues that had long been settled. Last week, the Colorado Court of Appeals held

We conclude that a parent’s assertion of Indian heritage, standing alone, is insufficient to trigger ICWA’s notice requirements but, rather, it invokes the petitioning party’s obligation to exercise

People in re J.L., 2022 COA 43, P3

due diligence under section 19-1-126(3). We further conclude that the exercise of due diligence under this provision is flexible and depends on the circumstances of, and the information presented to the court in, each case. Nonetheless, the record needs to show that the petitioning party earnestly endeavored to gather additional information that would assist the court in determining whether there is reason to know that the child is an Indian child.

And now, “due diligence” is an “earnest endeavor” on the part of the state when a parent tells the Court they have tribal relations. However, in both cases the court of appeals sent the case back due to the lack of “due diligence” to follow up on these statements by the parents. The Court in A-J.A.B. gives a very detailed remand instruction regarding due diligence, and what the Court will need by date certain.

To lower my blood pressure and end this post, I will remember what the Washington Supreme Court held, when faced with very similar facts and laws:

We hold that a court has a “reason to know” that a child is an Indian child when any participant in the proceeding indicates that the child has tribal heritage. We adopt this interpretation of the “reason to know” standard because it respects a tribe’s exclusive role in determining membership, comports with the canon of construction for interpreting statutes that deal with issues affecting Native people and tribes, is supported by the statutory language and implementing regulations, and serves the underlying purposes of ICWA and WICWA. Further, tribal membership eligibility varies widely from tribe to tribe, and tribes can, and do, change those requirements frequently. State courts cannot and should not attempt to determine tribal membership or eligibility. This is the province of each tribe, and we respect it.

In re Z.J.G., 471 P.3d 853, 865.

So for the first time since 2015, I’m giving myself permission to only read the reported ICWA cases rather than all of the unreported ones. So what does California do? Start reporting way more cases! Five in this first quarter (as opposed to 1 in 2021).

This case itself notes that this is not a particularly unique, but that by reporting it, just the reporting might lead to compliance.

We publish our opinion not because the errors that occurred are novel but because they are too common. Child protective agencies and juvenile courts have important obligations under ICWA. Failing to satisfy them serves only to add unnecessary uncertainty and delay into proceedings that are already difficult for the children, family members, and caretakers involved. Delayed investigation may also disadvantage tribes in cases where it turns out ICWA does apply, as their opportunity to assume jurisdiction or intervene will come at a late stage in the proceeding.

Unfortunately, I don’t think just reporting a case will lead to compliance, especially when this is the final result:

We conditionally reverse the section 366.26 orders. On remand, the juvenile court shall (1) direct CFS to comply with the inquiry and notice provisions of ICWA and sections 224.2 and 224.3 and update the court on their inquiry and the tribes’ responses and (2) determine whether ICWA applies. If the court determines ICWA does not apply, the orders terminating parental rights shall be reinstated and further proceedings conducted, as appropriate.

(emphasis added)

I haven’t crunched the numbers, but I am not convinced conditional reversal helps with compliance. Vivek Sankaran made this argument in the In re Morris case here in Michigan, and the sheer numbers in California indicate conditional reversal doesn’t seem to do much to change practice. I’m not sure reporting the case will change that. I still believe we should be reporting far more of the ICWA cases than we currently do, given that only about 20% of total ICWA appellate cases are reported.

These kind of cases feel like they are coming in a rapid speed right now–this is the third one I am aware of that have been/will be decided this spring. The issue is the attempted interference by foster parents in a transfer to tribal court proceeding, usually by trying to achieve party status.

Having considered the parties’ briefing — and assuming without deciding both that J.P. and S.P. were granted intervenor-party status in the superior court and that such a grant of intervenor-party status would have been appropriate4 — we dismiss this appeal as moot. “If the party bringing the action would not be entitled to any relief even if it prevails, there is no ‘case or controversy’ for us to decide,” and the action is therefore moot.5 As explained in our order of July 9, 2021, even if we were to rule that the superior court erred in transferring jurisdiction, we lack the authority to order the court of the Sun’aq Tribe, a separate sovereign, to transfer jurisdiction of the child’s proceeding back to state court.6 And we lack authority to directly review the tribal court’s placement order.7

The Court cites my all time favorite transfer case–In re M.M. from 2007. Not only is that decision a complete endorsement of tribal jurisdiction, it also explains concurrent jurisdiction (especially useful when you are operating in a PL280 state), which is not the power to have simultaneous jurisdiction, but the power to chose between two jurisdictions.

When we speak of “concurrent jurisdiction,” we refer to a situation in which two (or perhaps more) different courts are authorized to exercise jurisdiction over the same subject matter, such that a litigant may choose to proceed in either forum.FN13 As the Minnesota Supreme Court explained in a case involving an Indian tribe, “[c]oncurrent jurisdiction describes a situation where two or more tribunals are authorized to hear and dispose of a matter *915 and the choice of which tribunal is up to the person bringing the matter to court.” (Gavle, supra, 555 N.W.2d at p. 290.) Contrary to Minor’s apparent belief, that two courts have concurrent jurisdiction does not mean that both courts may simultaneously entertain actions involving the very same subject matter and parties.

This is a very useful decision directly addressing one for the most difficult parts of a transfer process–whether the state court will use a best interest analysis to determine jurisdiction.

These are not reasons to deny a tribe jurisdiction over a child welfare case:

The State argued that transfer should be denied because of the lack of

responsibility by Mother and Father, the efforts of the foster parents to promote

the children’s Native American heritage, and the good relationship between the

current professionals and the children. The guardian ad litem for the children

joined the State in resisting the transfer of the case to tribal court.

Oh, and would you look at that, a CASA:

The juvenile court noted that the court appointed special

advocate (CASA) for the children recommended that the parental rights of the

parents be terminated and the children continue living with the foster parents.

But don’t worry–the Iowa Supreme Court clearly channeled the Washington Supreme Court in its thoughtful discussion of ICWA and its purpose, summarizing that

The federal ICWA and accompanying regulations and guidelines establish a framework for consideration of motions to transfer juvenile matters from state court to tribal court. Although good cause is not elaborated at length, both the statute and regulations state in some detail what is not good cause. Absent an objection to transfer or a showing of unavailability or

substantial hardship with a tribal forum, transfer is to occur. Clearly, Congress has an overall objective in enacting ICWA to establish a framework for the preservation of Native American families wherever possible.

The Court goes on to discuss the Iowa ICWA at length, along with some bad caselaw in Iowa, specifically the In re J.L. case, which is a really awful decision and has been a pain to deal with for years.

This Court states,

State courts have struggled with the statutory question of whether federal

or state ICWA statutes permit a child to raise a best interests challenge to

transfer to tribal courts. In In re N.V., 744 N.W.2d 634, we answered the

question. After surveying the terms of the federal and state ICWA statutes, we

concluded that the statutes did not permit a child to challenge transfer on best

interests grounds. Id. at 638–39.***

In short, there can be no substantive due process violation arising from a

statute that refuses to allow a party to present on an issue irrelevant to the

proceeding. To that extent, we overrule the holding ofIn re J.L. (emphasis ADDED)

***

In conclusion, if there is no objecting child above the age of twelve, we hold

that the transfer provisions of ICWA which do not permit a child from raising the

best interests of the child to oppose transfer does not violate substantive due

process.

Therefore,

In an ICWA proceeding, the United States Supreme Court observed that

“we must defer to the experience, wisdom, and compassion of the . . . tribal

courts to fashion an appropriate remedy” in Indian child welfare cases. Holyfield,

490 U.S. at 54 (quoting In re Adoption of Halloway, 732 P.2d at 972). These

observations apply in this case

There is a small dissent on whether the Father could appeal this case, but no issues with the Tribe’s appeal. Also, a reminder that the issue of jurisdiction was never a question Brackeen and decisions like this one are tremendously helpful for tribes seeking to transfer cases.

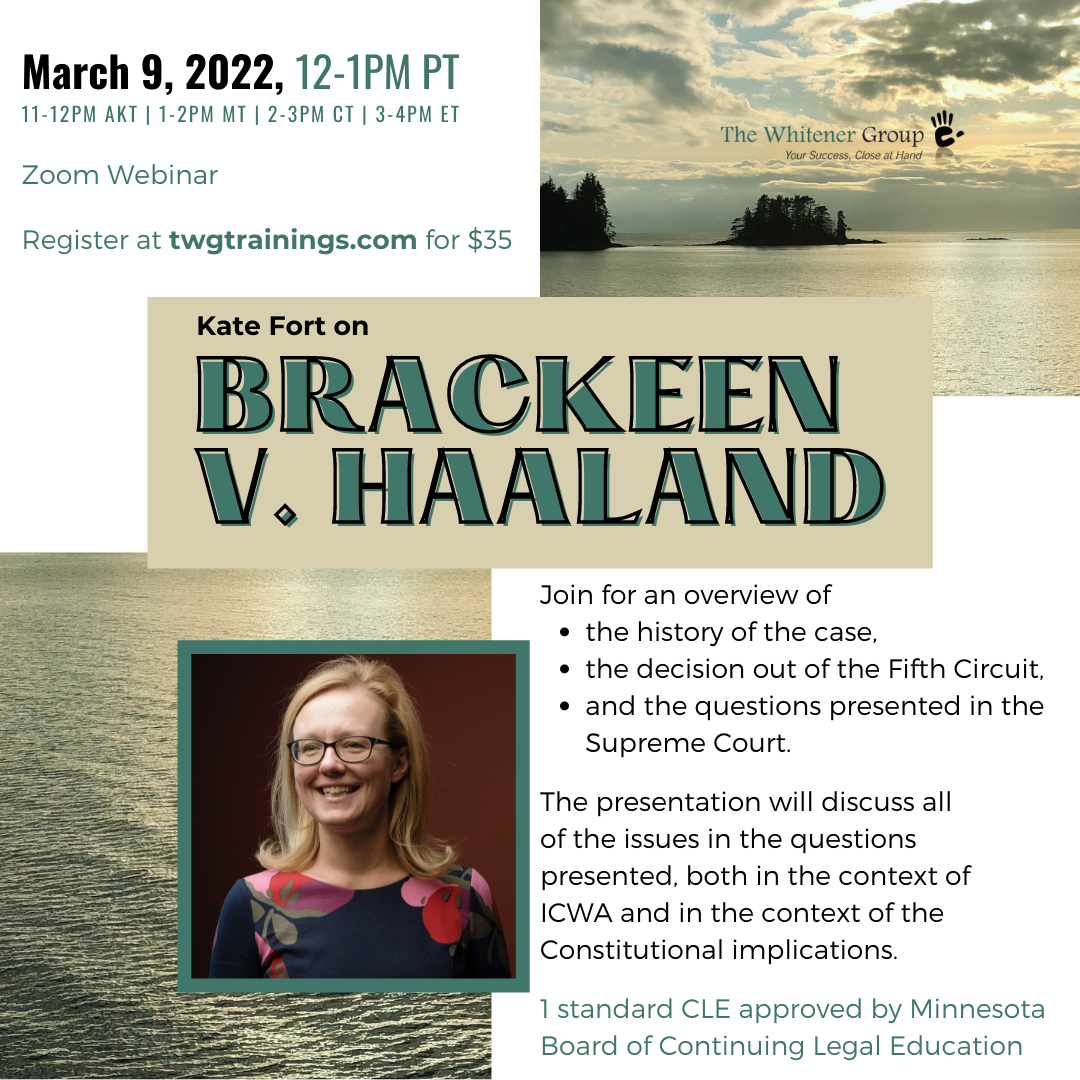

Since we all now have to deal with it, might as well deal with it together:

The Court granted the petition with no limitations, so the issues are not limited the way the government and four tribes requested. Arguments will be held next term (terms start in October, so after October, 2022).

Even though this is not an ICWA case, three people have sent me this opinion by Justice Montoya Lewis regarding the primacy of relative placement in child protection proceedings. This opinion points to all sorts of issues that beleaguers relative placement, especially certain aspects of background checks and prior involvement with the system. Here, the Court explicitly holds that prior involvement in the system alone cannot be consider as a reason to keep a child out of a relative placement, and seems to imply that both criminal history and immigration status cannot be considered either.

But no wonder the ICWA advocates noted this case–you can see ICWA’s influences implicitly and explicitly throughout:

This statutory scheme makes it clear that both the Department and the courts are directed by the legislature to preserve the family unit and, when unable to do so, to place the child with family members, relatives, or fictive kin before looking beyond those categories to nonrelatives.

***

This means that the dependency court is charged with actively

ensuring that relative placements have been fairly evaluated. This is an active

process required at each hearing. Id. Making a finding that no such family

placements exist at one hearing does not mean that the inquiry ends: the statute

contemplates that the inquiry is ongoing, recognizing that family circumstances

change, as they so often do, and as they did in this very case. Id.

(emphasis added)

Courts must do more than give a passing acknowledgment for relative preference,

as occurred in this case. Courts must actually treat relatives as preferred placement

options and cannot use factors that operate as proxies for race or class to deny

placement with a relative.***

Prior involvement with child welfare agencies, without more, can serve as a proxy for race or class, given that families of Color are disproportionately impacted by the child welfare system.11 [!!!!!!]

(emphasis and punctuation added and oh BY THE WAY what does that footnote 11 say?? Is it a very long footnote on ICWA, the gold standard?? Now THAT is a long footnote I don’t mind reading):

11 For example, under the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA)—the “gold standard” in child welfare policy—children in foster care or preadoptive placement “shall be placed in the least restrictive setting which most approximates a family” with highest preference to a member of the child’s extended family, absent “good cause to the contrary.” 25 U.S.C. § 1915(b); BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS , U.S. DEP ’ T OF INTERIOR, GUIDELINES FOR I MPLEMENTING THE INDIAN CHILD

WELFARE A CT 39 (2016). A party seeking to deviate from this placement preference must state their reasons on the record and bears the burden of proving by clear and convincing evidence that there is good cause to depart from the placement preference. 25 C.F.R. § 23.132(a), (b). One reason a court may conclude that there is good cause to depart from the placement preference is the unavailability of a suitable placement, but “the standards for determining whether a placement is unavailable must conform to the prevailing social and cultural standards of the Indian community in which the Indian child’s parent or extended family resides or with which the Indian child’s parent or extended family members maintain social and cultural ties,” and socioeconomic status may not be a basis to depart from the placement preference. 25 C.F.R. § 23.132(c)(5), (d). Notably, prior contact with the child welfare system, criminal history, and poverty are not good cause reasons to depart from the strong preference for placement with relatives under ICWA. Likewise, tribes located around Washington State prioritize placement with extended family or other members of the tribal community and rarely treat factors like prior child welfare proceedings or criminal history as disqualifying in determining out-of-home placements for children. See, e.g., NISQUALLY TRIBAL CODE § 50.09.09; NOOKSACK LAWS & ORDINANCES § 15.09.100; JAMESTOWN S’ KLALLAM TRIBE T RIBAL CODE § 33.01.09(J); PUYALLUP TRIBAL C ODE § 7.04.840. But see TULALIP TRIBAL CODE § 4.05.110(4) (prohibiting placement with someone with a criminal conviction, but only for certain crimes identified as disqualifying crimes by the social services division charged by the Tulalip Tribe with the responsibility to protect the health and welfare of Tulalip families and their children (beda?chelh)).

Finally, “Courts must afford meaningful preference to placement with relatives.” (not my emphasis this time)

The Washington Supreme Court is doing very important work right now, as are some of the best child protection activists/litigators in the country (IYKYK).

DSS and the guardian ad litem for Carrie (GAL) disagree, arguing that respondent

conflates the existence of or possibility of a distant relation with an Indian with

reason to know that a child is an Indian child.

States and courts are really struggling with how much information from a parent gives the court reason to know there is an Indian child in the case–I think this is especially since the regulations now make clear that if you do have reason to know, you must treat the child as an Indian child until demonstrated otherwise. At the same time, there is real issue with lack of nuance on this issue–when a trial court takes the facts from a case like In re Z.J.G. and treats them the exact same way as the facts in this case, which is essentially what happened, then states really have to go send notice for both, which is what the WA Supreme Court held. You don’t do the reverse, which is what the North Carolina Supreme Court has done in this case.

Now, I got an email from California recently and there is a lot of discussion there about the state’s laws there distinguishing between “reason to believe” and “reason to know.” There are a LOT of bumps with implementation, but they are essentially requiring a level, or duty, of inquiry and further inquiry from their state workers to ensure they aren’t missing ICWA cases.

I’d love to get into why is the GAL arguing against the application of ICWA or ensuring the child has the information she may need to be a tribal citizen, but I do have to do some other things today . . . https://turtletalk.blog/2013/11/25/fletcher-fort-indian-children-and-their-guardians-ad-litem/

You must be logged in to post a comment.