Here is the majority opinion in In re Peters/Brinton/Mathews and in In re Brinton (note the complete absence of any mention of ICWA or MIFPA)

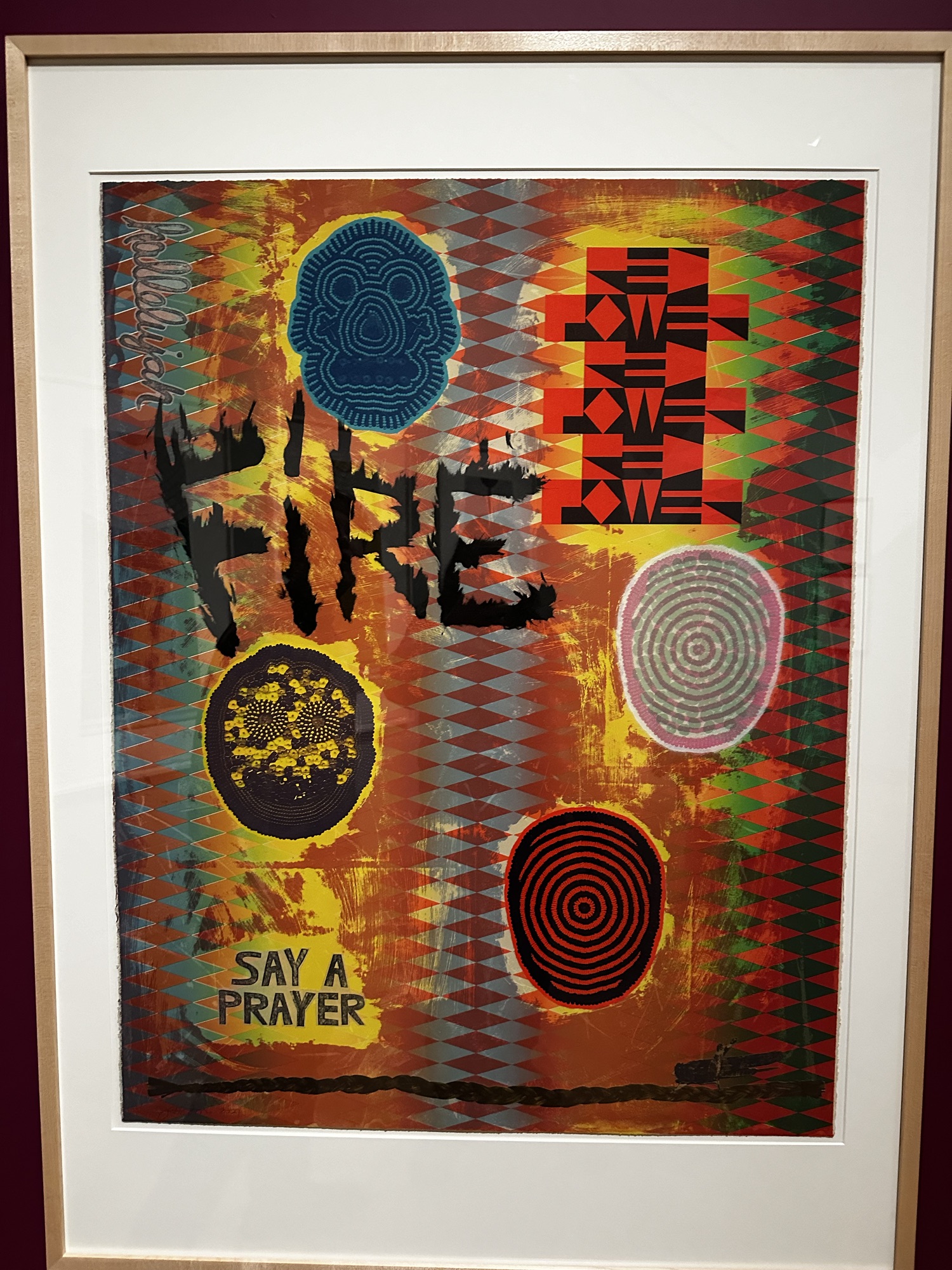

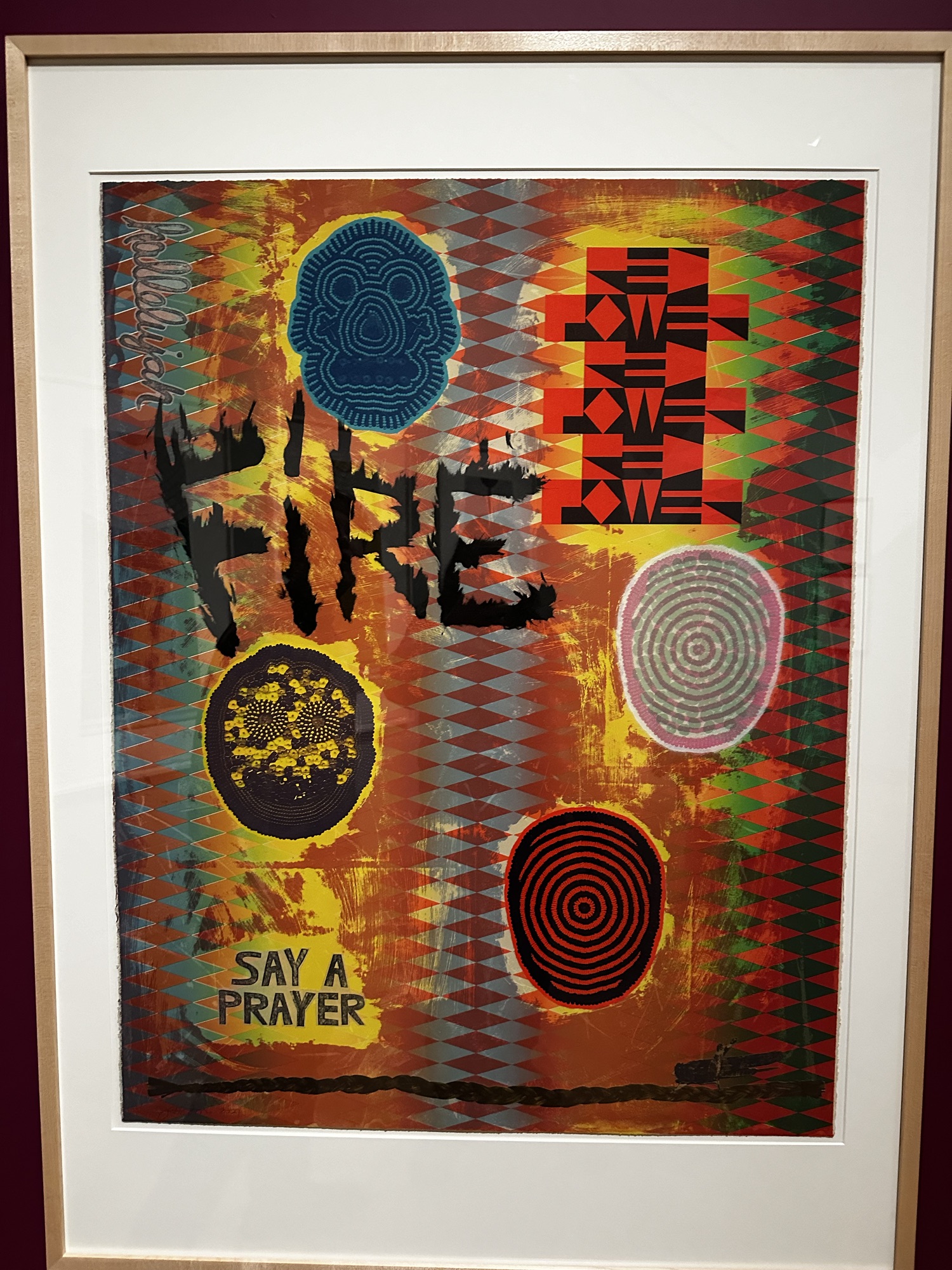

And here is Judge Maldonado’s dissent, which is based entirely on ICWA/MIFPA and is 🔥:

Here is the majority opinion in In re Peters/Brinton/Mathews and in In re Brinton (note the complete absence of any mention of ICWA or MIFPA)

And here is Judge Maldonado’s dissent, which is based entirely on ICWA/MIFPA and is 🔥:

Here.

There has been a small spate of Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction Enforcement Act cases this year involving family law cases and tribal courts. In most states, tribes are considered “states” for the purposes of determining a child’s “home state” jurisdiction. These are generally (but not always) non-ICWA cases like parental custody and child support. These kind of cases seem rare to practitioners, but nationally there’s a fair number of them (and will continue to be the kind of reasoning tribal and state judges will need to engage in to as more and more cases arise in this subject area).

McGrathBressette (Michigan, child custody v. child protection)

MontanaLDC (Montana, child custody)

NevadaBlount (Nevada, third party custody)

(And yes, I have a pile of ICWA cases to share with you that have built up in the last month or so.)

Here is the opinion and the materials in People v. Magnant:

Prior post here.

Not sure what’s going on, but here are the (unpublished) cases so far this year:

| In re King/Koon | 7-Jan | 2020 | Court of Appeals | Grand Traverse | Michigan | Un | Notice |

| In re K. Nesbitt | 11-Feb | 2021 | Court of Appeals | Hillsdale | Michigan | Un | Notice |

| In re Stambaugh/Pantoja | 11-Feb | 2021 | Court of Appeals | St. Joseph | Michigan | Un | Notice |

| In re Banks | 18-Feb | 2021 | Court of Appeals | Wayne | Michigan | Un | Notice |

| In re Dunlop-Bates | 18-Feb | 2021 | Court of Appeals | Livingston | Michigan | Un | Active Efforts |

| In re Cottelit/Payment | 18-Mar | 2021 | Court of Appeals | Chippewa | Michigan | Un | Qualified Expert Witness |

For comparison, Michigan had 6 cases total in 2020, 7 in 2019, 8 in 2018. These counts include both published and unpublished cases–while I kind of understand why the Court of Appeals designates so many as unpublished, it obscures how many MIFPA cases we have if we only count published cases.

Here is the opinion in People v. Caswell:

An excerpt:

Defendant, Walter Joseph Caswell, is a member of the Mackinac Tribe of Odawa and Ojibwa Indians (the “Mackinac Tribe”). In October 2018, a Department of Natural Resources (DNR) conservation officer cited defendant for spear fishing in a closed stream in violation of MCL 324.48715 and MCL 324.48711.1 Defendant moved to dismiss the charges on the ground that he was a member of an Indian tribe or band granted hunting and fishing rights by 1836 and 1855 treaties with the United States federal government. The Mackinac County district court granted defendant’s motion upon concluding that the Mackinac Tribe was entitled to rights under the relevant treaties. On appeal from the prosecutor, the Mackinac County circuit court reversed on the ground that the Mackinac Tribe was not federally recognized and that federal tribal recognition is a matter for initial determination by the United States Department of the Interior. We granted defendant’s delayed application for leave to appeal. For the reasons explained below, we vacate the circuit court’s order and remand the case to the district court for an evidentiary hearing consistent with this opinion.

Briefs:

Here is the opinion in Smith v. Landrum (Mich. Ct. App.):

An excerpt:

The question presented in this quiet title action is whether a state court has subject-matter jurisdiction to decide an easement dispute in favor of a non-Indian on land owned by a non-Indian when the land is located on an Indian reservation. The trial court concluded that it did not, and therefore entered a final order granting defendants’ motion for summary disposition under MCR 2.116(C)(4) (lack of subject-matter jurisdiction).1 For the reasons outlined below, we hold that the trial court had subject-matter jurisdiction over the easement dispute. We therefore reverse the order granting defendant’s motion for summary disposition, and remand for further proceedings.

Here are the materials in MacLeod v. Braman (E.D. Mich.):

19 DCT Order Denying Motion to Appoint Counsel

Michigan COA decision:

Here are materials so far in the cases captioned People v. Davis and People v. Magnant:

Circuit Court materials:

Defendants Motion to Quash Information

People Response to Due Process Motion

People Response to Motion to Quash

People Response to Motion to Suppress

Here is “Legal gears on Nestle water cases grind slowly in Michigan” from MLive.

You must be logged in to post a comment.