Here are the materials in El-Meligi v. Navajo Health Foundation — Sage Memorial Hospital, Inc. (Ariz. Super.):

Here are the materials in El-Meligi v. Navajo Health Foundation — Sage Memorial Hospital, Inc. (Ariz. Super.):

Here are the materials in McKinsey & Company v. Boyd (W.D. Wis.):

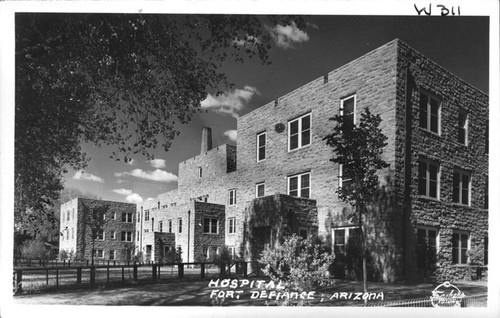

Here are the materials in Fort Defiance Indian Hospital Board v. Beccera (D.N.M.):

Here are the materials in Mestek v. Lac Courte Oreilles Community Health Center (W.D. Wis.):

Here is the opinion in Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe v. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan.

An excerpt:

The Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe and its Benefit Plan brought federal and common law claims against Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM or Blue Cross) for failing to fulfill its fiduciary duties in administering tribal health insurance plans. When we first encountered this dispute three years ago, we reversed the district court’s dismissal of the Tribe’s claims based on Blue Cross’s alleged failure to insist on “Medicare-like rates” for care authorized by the Tribe’s Contract Health Services1 program and provided to tribal members by Medicare-participating hospitals. On remand, the district court granted summary judgment to Blue Cross, concluding that the Tribe’s payments for qualified CHS care through the Blue Cross plans were not eligible for Medicare-like rates. The district court interpreted the relevant federal regulations as limiting the requirement of Medicare-like rates to payments for care that was authorized by CHS, provided to tribal members by Medicare- participating hospitals, and directly paid for with CHS funds. Based on the plain wording of the applicable regulations, we REVERSE and REMAND the case to the district court for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Briefs:

Lower court materials here.

Here are the materials in Southcentral Foundation v. Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (D. Alaska), on remand from the Ninth Circuit (materials here):

316 Southcentral Motion for Summary

Aila Hoss has posted “Securing Tribal Consultation to Support Tribal Health Sovereignty,” forthcoming in the Northeastern University Law Review, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

Effective intergovernmental coordination is essential to promoting health and safety. Yet, the current political climate has seen discord between Tribes, states, and the federal government on issues ranging from public health to environmental protection, among countless others. The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified this discord. Many states have challenged Tribal authority to access data, implement quarantine and isolation measures, and establish checkpoints and mask mandates. The federal government has delayed access to COVID-19 data, established burdensome and inconsistent policies for the use of federal response funds, and failed to meet its obligations to provide health care in many American Indian and Alaska Native communities.

As sovereign nations, Tribes have authority and responsibility over their land and people. Modern relationships between Tribes, states, and the federal government are based on the colonization and genocide, legalized by the United States under federal Indian law. Federal Indian law both recognizes Tribal sovereignty but also carves out instances in which a Tribe’s criminal or civil jurisdiction can be infringed. It has allowed federal agencies, Congress, and federal courts to exercise overwhelming authority to determine the scope of Tribal and Indigenous rights. And yet, Native representation in these same branches have been abysmal.

One method for ensuring Tribal and Native perspectives in these decision-making processes has been through Tribal consultation. Consultation is a formal, government-to-government process that requires governments to consult with Tribes before taking actions that would impact them.

Tribal consultation is essential for effective Indian health policy. This article argues for a more robust mechanism for Tribal consultation for health policy issues. Section I briefly describes Tribal governments and their relationship to the federal government. Section II summarizes existing requirements for Tribal consultation under federal and state law. Section III describes the limitations of existing Tribal consultation practices. Finally, section IV describes the impact of inadequate consultation on American Indian and Alaska Native health and offers recommendations for a Tribal consultation framework that fully supports American Indian and Alaska Native health.

Here are the materials so far in Ray v. United States (D.N.M.):

You must be logged in to post a comment.