These excerpts are interesting:

Found in the AAIA archive. . . .

Bethany R. Berger has posted “Rosalind’s Refund: The Woman, the Lawyers, and the Time that Created McClanahan v. Arizona,” forthcoming in the Kansas Law Review, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

Rosalind McClanahan was just twenty-two when she set one of the most important cases in federal Indian law into motion. On April 1, 1968, she filed her Arizona tax return, along with a protest that all the money withheld from her pay—$16.29—should be refunded because she was a Navajo citizen whose income was earned entirely on the Navajo reservation. The Arizona Tax Commission ignored her claim and the Arizona courts rejected it. But the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in her favor, building a foundation for many more decisions rebuffing state jurisdiction as well as landmark legislation such as the Indian Child Welfare Act and Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. This Essay, the first full history of McClanahan, examines the origins of the decision as part of the Kansas Law Review’s symposium on impact litigation in Indian country.

Rosalind McClanahan was born in an era of renewed pressure for Indian assimilation but came of age as tribes and Indigenous people increasingly insisted on self-determination. This moment had a direct influence on her case: her education at Window Rock High School (where she was elected Class Treasurer) resulted from new pathways to challenge Indian exclusion from public schools; her employer was the First Navajo National Bank, which opened in 1962 as the first bank on the 16-million-acre Navajo Nation; and her lawyers came from Diné be’iiná Náhiiłna be Agha’diit’ahii-Legal Services (shortened to “DNA”), which the Navajo Nation brought to the reservation as part of a new wave of federally funded organizations providing legal services to the poor. Each of these developments shaped both the decision and its impact.

I really enjoyed this article, especially the origin story of the DNA-People’s Legal Services. Recommended!!

Alexandra Fay has posted “”Subject to the Jurisdiction Thereof”?: Citizenship and Empire in Elk v. Wilkins,” forthcoming in the Washington & Lee Law Review, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

In 1884, the Supreme Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship did not apply to Native Americans. In Elk v. Wilkins, the Court denied John Elk the right to vote on the grounds that he was born a tribal member, not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, and thus ineligible for citizenship. This Article explores that decision, its context, and its consequences. It considers the radical promise of the Fourteenth Amendment’s text alongside the intentions of its Framers and the expectations of minority litigants. It situates Elk in a transformative period for both federal Indian policy and American federalism. The Article offers several readings of the Elk decision. It explores both the racist paternalism and the respect for tribal sovereignty evident in the Court’s reasoning, as well as the rapid shifts in Indian policy coinciding with Reconstruction. It ultimately argues that Elk v. Wilkins is emblematic of a distinct inflection point in federal Indian law, in which the Court’s formal adherence to longstanding principles of tribal sovereignty could simultaneously service federal assimilationist policy goals and a larger turn to American empire.

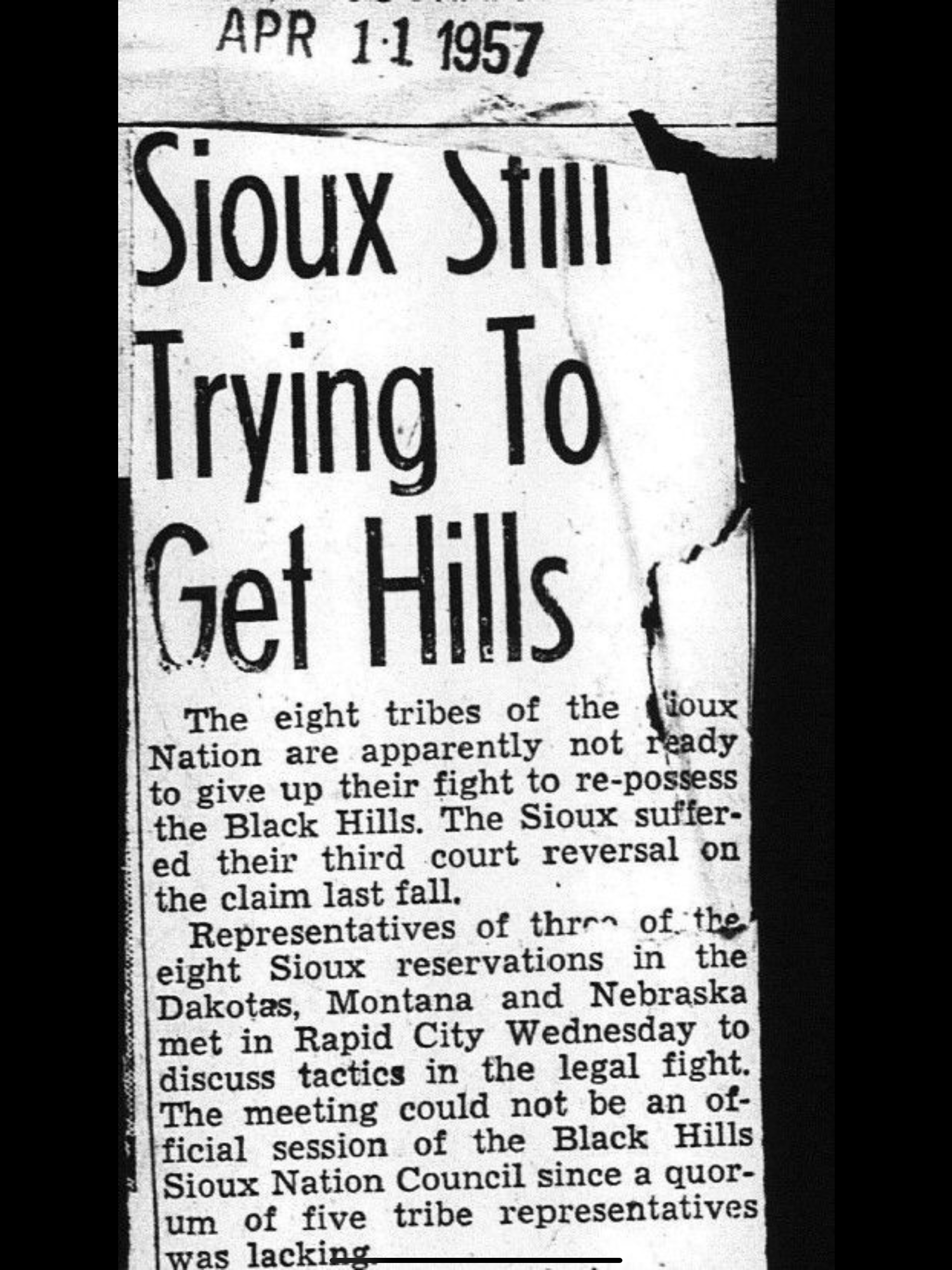

Frank Pommersheim and Bryce Drapeau have published “United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians Revisited: Justice, Repair, and Land Return” in the South Dakota Law Review. PDF

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED!! A Frank Pommersheim joint is always worth it.

The abstract:

The amazing legal journey of this case begins in 1923 and ends with a Sioux Nation of Indians “victory” in the Supreme Court in 1980. Before reaching the Supreme Court, the case was litigated four different times before the Court of Claims because of the ineffective assistance of counsel and the necessity of a congressional statute to clear away the threatening ghost of res judicata. The historical backstory begins not in 1923, but with the signing of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 and the United States’ illegal taking of the sacred Black Hills in1877. And the case does not end with the Sioux “victory” before the Supreme Court and its award of “just compensation” for the illegal taking. The Sioux Nation of Indians rejected—and continues to reject—the remedy of financial compensation without an attendant search for mutual repair and a justice that includes some form of land return. Despite some modest examples of land return in other parts of Indian country, no such efforts involve the Black Hills. This article seeks to inform all, but particularly those two generations of Lakota and non-Native citizens born since 1980, that now is the time for renewed effort and commitment to realize reconciliation and a justice that includes land return. This must be done before history closes its door for a second and final time and the Black Hills will remain stranded in historical infamy. No, this article is not just another twist on classic Indian Law principles gone awry, but the first of something we might call the Historical (Trauma) Trilogy of stealing Lakota land (and breaking treaties), suppressing the teaching and learning of the Lakota language and culture, and the battering ram of boarding schools to break-up Lakota families where a core value has always been to be a “good relative.” In its own careful way, this article is also about the persistence of Lakota resistance and the hard work of restoring the (sacred) hoop of land, language, and family for these new days.

Gregory Ablavsky and Bethany Berger have posted “Subject to the Jurisdiction Thereof: The Indian Law Context,” forthcoming in the NYU Law Review Online, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides that “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” Much of the debate over the meaning of this provision in the nineteenth century, especially what it meant to be “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States, concerned the distinctive status of Native peoples—who were largely not birthright citizens even though born within the borders of United States.

It is unsurprising, then, that the Trump Administration and others have seized on these precedents in their attempt to unsettle black-letter law on birthright citizenship. But their arguments that this history demonstrates that jurisdiction meant something other than its ordinary meaning at the time—roughly, the power to make, decide, and enforce law—are anachronistic and wrong. They ignore the history of federal Indian law.

For most of the first century of the United States, the unique status of Native nations as quasi-foreign entities was understood to place these nations’ internal affairs beyond Congress’s legislative jurisdiction. By the 1860s, this understanding endured within federal law, but it confronted increasingly vocal challenges. The arguments over the Fourteenth Amendment, then, recapitulated this near century of debate over Native status. In crafting the citizenship clause, members of Congress largely agreed that jurisdiction meant the power to impose laws; where they heatedly disagreed was whether Native nations were, in fact, subject to that authority. Most concluded they were not, and in 1884, in Elk v. Wilkins, the Supreme Court affirmed the conclusion that Native nations’ quasi-foreign status excluded tribal citizens from birthright citizenship.

But the “anomalous” and “peculiar” status of Native nations, in the words of the nineteenth-century Supreme Court, means that the law governing tribal citizens cannot and should not be analogized to the position of other communities—or at least any communities who lack a quasi-foreign sovereignty and territory outside most federal and state law but within the borders of the United States. Indeed, the Court in Wong Kim Ark expressly rejected the attempt to invoke Elk v. Wilkins to deny birthright citizenship to a Chinese man born in the U.S. to non-citizen parents, ruling that the decision “concerned only members of the Indian tribes within the United States.” The analogy has no more validity today than it did then, and the current Court should continue to reject it.

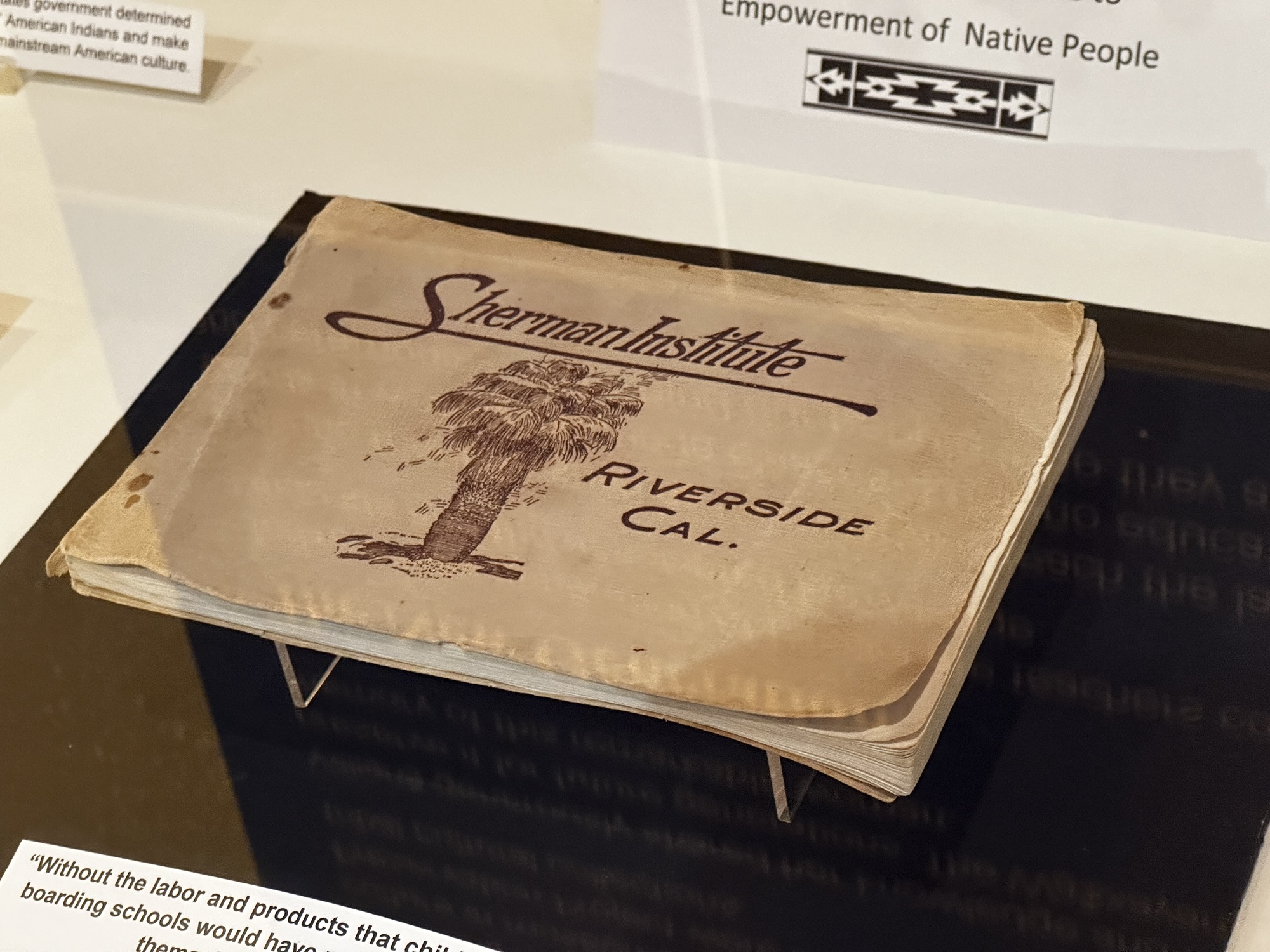

Matthew Villaneuve has published “Habeas Corpus and American Indian Boarding Schools: Indigenous Self-Determination in Body and Mind, 1880–1900” in the Western Historical Quarterly.

Abstract:

This article examines the history of Native people’s use of habeas corpus to resist family separation employed in the United States’ system of Indian boarding schools. It highlights three cases brought by Native petitioners from Alaska, New Mexico, and Iowa between 1885 and 1900. These cases show how Native parents, husbands, and cousins challenged the federal agents responsible for boarding schools by appealing to federal courts for intervention on behalf of their kin confined in such schools. Moving beyond legal interpretations, however, this article further argues that Native people used these petitions to assert their capacity to make their own decisions about the proper education of their young people and to convey Indigenous values of teaching and learning. Consequently, these cases illustrate an important but understudied means by which Native people used the legal tools available to them to assert self-determination in education. These habeas corpus cases are therefore a crucial part of boarding school history, American Indian and Indigenous history, and the history of U.S. education.

You must be logged in to post a comment.