Author: Wenona T. Singel

DOGE Plans to Close 41 Offices of the BIA, IHS, NIGC, and DOI Office of Hearing and Appeals – Probate Hearings Division

Below is a list of planned lease terminations pulled from the DOGE website on March 10, 2025. The list is likely incomplete and inaccurate, since DOGE’s “wall of receipts” has notoriously overstated its savings impact for federal taxpayers, requiring numerous corrections since it began posting details of its work.

The list below also includes plans for the closure of seven additional BIA offices. These additional closures were pulled from a table published by the Democrats on the House Natural Resources Committee.

“The impact on Bureau of Indian Affairs offices will be especially devastating. These offices are already underfunded, understaffed, and stretched beyond capacity, struggling to meet the needs of Tribal communities who face systemic barriers to federal resources. Closing these offices will further erode services like public safety, economic development, education, and housing assistance—services that Tribal Nations rely on for their well-being and self-determination.” – Rep. Jared Huffman (D-Calif.), Ranking Member of the House Natural Resources Committee

Mark Macarro, President of NCAI, explained to the A.P. that funding for the BIA, IHS, and the BIE represents the lion’s share of the government’s obligations to tribes, and last year those departments made up less than a quarter of 1% of the federal budget. “They’re looking in the wrong place to be doing this,” said Macarro. “And what’s frustrating is that we know that DOGE couldn’t be a more uninformed group of people behind the switch. They need to know, come up to speed real quick, on what treaty rights and trust responsibility means.”

| AGENCY | LOCATION | SQ FT | ANNUAL LEASE |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | CARNEGIE, OK | 0 | $2,798 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | ST. GEORGE, UT | 750 | $50,400 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | FREDONIA, AZ | 1,500 | $22,860 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE-CALIFORNIA | ARCATA, CA | 1,492 | $37,012 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE NAVAJO | FARMINGTON, NM | 2,000 | $62,677 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | PAWNEE, OK | 7,549 | $156,171 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | SEMINOLE, OK | 9,825 | $184,770 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE-BEMIDJI | BEMIDJI, MN | 4,896 | $133,916 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE -OKLAHOMA | OKLAHOMA CITY, OK | 5,000 | $119,951 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | WATONGA, OK | 2,850 | $38,573 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | PABLO, MT | 620 | $10,418 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | RAPID CITY, SD | 1,825 | $53,911 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | FORT THOMPSON, SD | 4,870 | $58,976 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | SISSETON, SD | 4,911 | $180,008 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE-BEMIDJI | TRAVERSE CITY, MI | 798 | $28,638 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | ZUNI, NM | 2,117 | $39,819 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE NAVAJO | GALLUP, NM | 20,287 | $322,529 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | ELKO, NV | 4,760 | $134,297 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | ASHLAND, WI | 34,970 | $649,408 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | SHAWANO, WI | 1,990 | $36,395 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE NAVAJO | SAINT MICHAELS, AZ | 40,924 | $1,074,931 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | PHOENIX, AZ | 71,591 | $1,784,239 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | REDDING, CA | 5,307 | $154,103 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | HOLLYWOOD, FL | 3,000 | $79,365 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE-PHOENIX | ELKO, NV | 853 | $22,240 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE-NASHVILLE | MANLIUS, NY | 2,105 | $37,648 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE-NASHVILLE | OPELOUSAS, LA | 1,029 | $25,015 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE-BEMIDJI | SAULT STE MARIE, MI | 1,100 | $34,375 |

| INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE-CALIFORNIA | UKIAH, CA | 1,848 | $45,857 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | PAWHUSKA, OK | 10,335 | $166,134 |

| NATIONAL INDIAN GAMING COMMISSION | RAPID CITY, SD | 1,518 | $43,938 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | TOPPENISH, WA | 17,107 | $533,985 |

| BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | BARAGA, MI | 1,200 | $14,400 |

| OFFICE OF HEARING AND APPEALS (PROBATE HEARINGS DIVISION) | RAPID CITY, SD | 2,252 | $53,198 |

| TOTALS | 270927 | $6,339,757 | |

| Additional Office Closures – House Natural Resources Committee List | |||

| BUREAU | LOCATION | PLANNED TERM. DATE | |

| 1409: BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | SHOW LOW, AZ | 1/26/2026 | |

| 1409: BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | TOWAOC, CO | TBD | |

| 1409: BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | LAPWAI, ID | 9/30/2025 | |

| 1409: BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | SAULT SAINT MARIE, MI | TBD | |

| 1409: BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | POPLAR, MT | TBD | |

| 1409: BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | FT TOTTEN, ND | TBD | |

| 1409: BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | EAGLE BUTTE, SD | TBD | |

BIE to Hold Tribal Consultations this Friday on Executive Order requiring Interior to Prepare a Plan for use of Federal BIE Funds for Schools of Choice

EO 14191, titled “Expanding Educational Freedom and Opportunity for Families” and signed on January 29, 2025, includes a section that seeks the implementation of schools of choice using federal BIE funds for families with children eligible to attend BIE schools.

Section 7 of the Order provides:

Helping Children Eligible for Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) Schools. Within 90 days of the date of this order, the Secretary of the Interior shall review any available mechanisms under which families of students eligible to attend BIE schools may use their Federal funding for educational options of their choice, including private, faith-based, or public charter schools, and submit a plan to the President describing such mechanisms and the steps that would be necessary to implement them for the 2025-26 school year. The Secretary shall report on the current performance of BIE schools and identify educational options in nearby areas.

On February 28, 2025, the BIE issued a Dear Tribal Leader Letter announcing two expedited tribal consultation webinars for Tribal leaders and the public scheduled for this Friday, March 14, 2025. The links to register for either of Friday’s consultations are in the letter. Written comments can also be submitted by email to consultationcomments@bie.edu.

The National Indian Education Association (NIEA) has shared its concerns about BIE School Choice here.

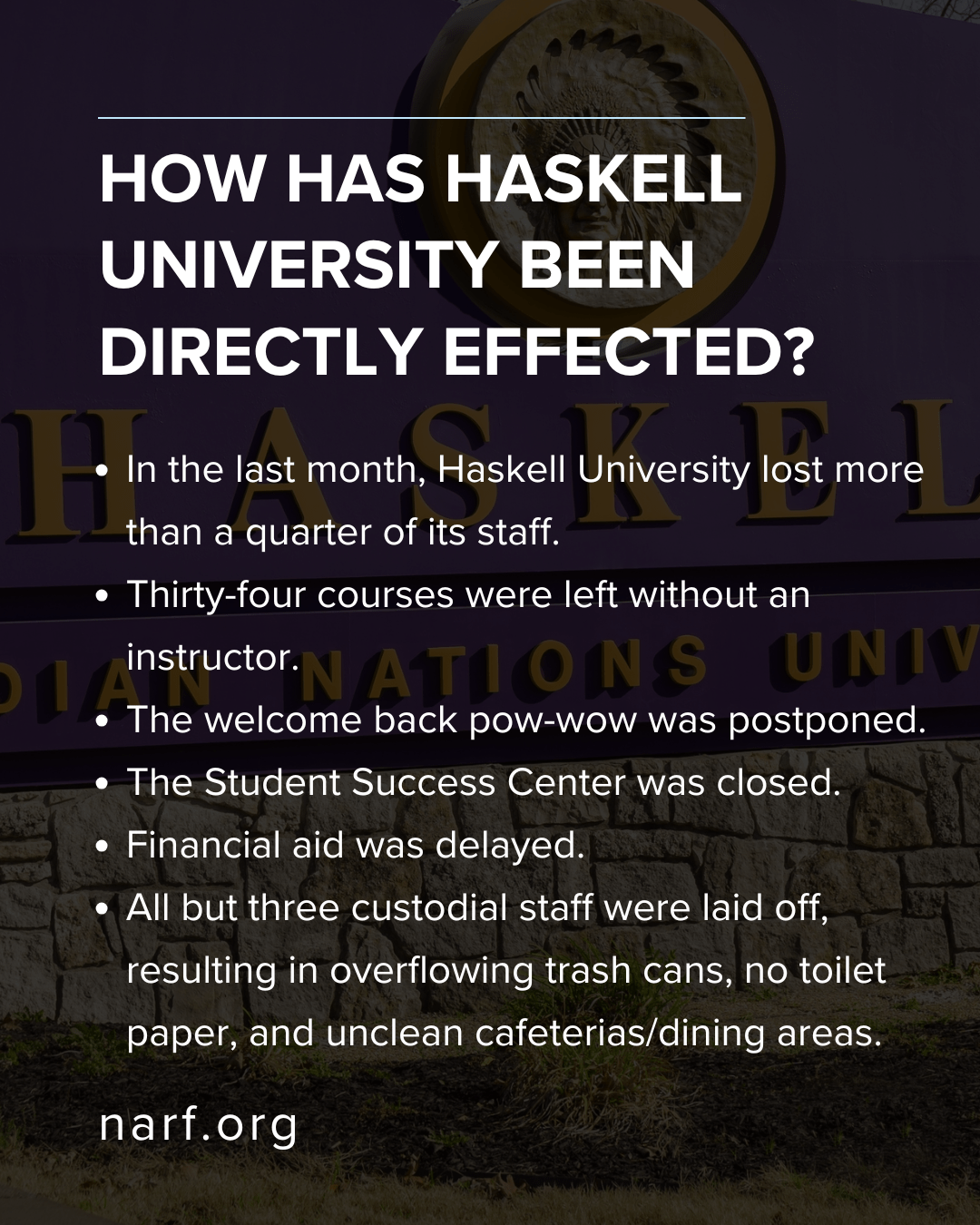

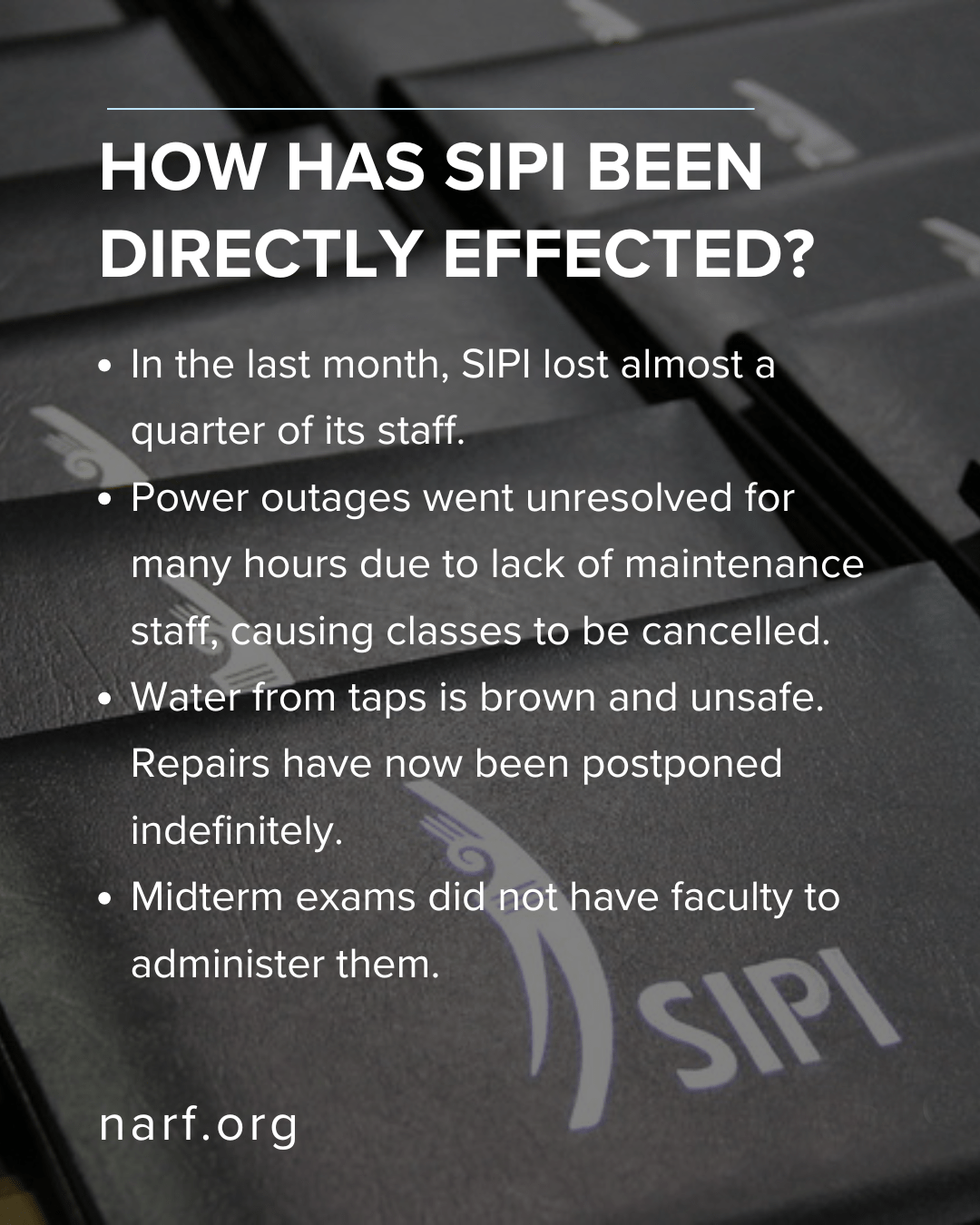

NARF files suit on behalf of Tribes and Students Challenging Reductions at the Bureau of Indian Education, Haskell Indian Nations University, and Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute (SIPI).

The complaint, available below, was filed on March 7 in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. The Tribal plaintiffs include the Pueblo of Isleta, Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, and Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, and the complaint names the Secretary of Interior Doug Burgum, Assistant Secretary – Indian Affairs Bryan Mercier, and Director of BIE Tony Dearman as defendants.

Deb Haaland officially launches campaign for governor of New Mexico

“If elected, she will be the first Native American woman to serve as a governor in the United States,” her campaign wrote.

Wenona Singel: “Intergenerational trauma to indigenous families is real”

From MSU Today, here is “Faculty voice: Intergenerational trauma to indigenous families is real.”

Wenona Singel

Professor of Law and Director of Indigenous Law and Policy Center Wenona Singel is currently researching and writing a book on her family’s multi-generational experience with forcible removal of Indian children in U.S. history. Below is an excerpt.

Five generations of my family experienced and responded to U.S. policies of forced displacement and assimilation. In 1840, my third-great-grandfather lost his Native family around the time of the U.S. military’s forcible mass detention and removal of Native people in southern Michigan.

He was raised by a Native family that moved from southern Michigan to the northern part of the Lower Peninsula. My ancestors lived in northern Michigan settled in a Native village at Burt Lake, where they purchased multiple lots of land. Later, they transferred title to that land to the Governor of Michigan to be held in trust for their benefit.

On October 15, 1900, Sheriff Fred Ming of Cheboygan County and a lumber speculator named John McGinn poured kerosene on the entire Native village at Burt Lake, destroying everything but the church and one small shack. Following that event, which is now referred to as the Burt Lake Burnout by Michigan Native communities, children of Burt Lake village, including my great-grandfather’s generation, were sent to the federally operated Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial School.

Indian boarding schools throughout the U.S. were well-documented sites of forcible assimilation, abuse, and neglect. Native children, who were frequently removed from their homes against their parents’ wishes, arrived at the schools, where they were stripped of their traditional clothing. Their hair was cut short, they were forbidden from speaking their Indigenous languages, they were taught menial skills, and they suffered from numerous forms of physical and sexual abuse as well as malnutrition, rampant spread of disease, and other forms of neglect.

Many Native children died during their institutionalization at Indian boarding schools, and the U.S. has only identified a portion of the grave sites of these children. Those who survived Indian boarding schools speak of persistent feelings of unworthiness and shame for being Indian.

My grandfather was among the children born to the generation that attended the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial School. He attended Holy Childhood School of Jesus, an Indian boarding school operated by the Catholic Church in Harbor Springs, Michigan.

At Holy Childhood, my grandfather met my grandmother, who also lived at the school. They later married and had five children, all of whom were taken from them by social services.

One of the lasting legacies of Indian boarding schools is that children who attended these schools grew up without exposure to their own families’ parenting skills. Instead, survivors grew up learning cooking and cleaning over academics and were subjected to institutional abuse.

These experiences deeply traumatized many survivors of the schools and left them unprepared for gainful employment and economic prosperity in adulthood. Furthermore, social services agencies in the twentieth century treated Native families as incapable of raising their own children.

By 1978, 25% to 35% of all Native children in the U.S. were removed from their homes and placed in foster care, adoptive homes, or institutions. In nearly all cases, Native children were placed with families who were not Native, leading to the widespread loss of children’s cultural identity and connection with their tribal communities.

Like so many of the Native children born in the 1950s, my mother was removed from her family as an infant and lived in multiple foster care homes until she was adopted by a white Catholic family with one of her biological sisters at the age of five.

My mother and aunt experienced loss of their Anishinaabe cultural identity. They also confronted cruel negative stereotypes about Native Americans in their schools, church, and family.

As an 18-year-old girl, my mother became pregnant with me and left her adoptive family. For three years, my mother and I “couch-surfed” in temporary housing until my sister was born and we found an income-pooling commune founded by a church in Detroit. The following year, when I was four, my baby sister was taken from us and adopted by a white family.

Today, I am a parent to two children. I am committed to documenting the impact of federal and state Indian law and policy on Native families and the intergenerational trauma it produces. I want my own children to be the first generation in my family since at least 1840 not to experience separation from their parents. (However, my sister lost custody of her son following life in the adoptive home that she fled during adolescence.)

I became extremely self-reliant as a child to compensate for the challenges my family had as a result of abuse and neglect. However, many negative impacts of the toxic stress of my early years continue to affect me today, such as constant hyper-vigilance and the sensation of being in survival mode, even though I’ve long established the security I lacked in my youth.

My story is not exceptional; rather, it’s representative of and part of a pattern common to Native families throughout the country. Themes of substance abuse, thoughts of suicide, domestic violence, lack of secure housing, and financial issues plagued the adults in my family, contributing to toxic stress.

On the Adverse Childhood Experiences scale, which measures children’s exposure to various forms of abuse, neglect, dysfunction, and chaos, I score an 8 out of 10. Scores of 8 through 10 are shared by an estimated 1% to 3% of the U.S. population.

I know many Native community members who score a 10 out of 10. Studies have shown that people with an ACE score of 4 or more have a greater likelihood of developing chronic health conditions, they are four times more likely to experience depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders than the general population, and they have a lower life expectancy.

They are also 12 times more likely to attempt suicide.

My work is intended to help other Native families understand how federal and state Indian policies have contributed to multiple generations of profound harm that continue to cause reverberating impacts in the present.

I am exploring how evidence-based strategies for surviving and thriving despite high ACE scores can be scaled and tailored to address historic trauma using culture, traditional teachings, and education.

I am also examining how our justice and political system might respond and provide remedies for the intergenerational harm.

I am an advocate of a multi-pronged approach that includes components such as an acknowledgement of the full effect of the harms experienced by Native families; formal and meaningful apologies; accountability for individuals, organizations, and governments; restitution; rehabilitation; and healing as defined and prescribed by Indigenous communities.

Try as they did, the federal and state governments did not succeed at whitewashing our people. It came close. And now they must take action on each of these prongs to help Indigenous people heal.

MSU College of Law Indigenous Law & Policy Center job announcement: Communications Coordinator

Please share with your networks!

The ILPC is seeking applicants for the position of Communications Coordinator. The deadline for applications is October 30, 2023, and the job description and application instructions are available at the link below:

https://careers.msu.edu/cw/en-us/job/515337/communications-coordinator

Position Summary

The College of Law Indigenous Law & Policy Center (ILPC) welcomes candidates who have a passion for working in a context dedicated to indigenous rights advocacy; experience working with indigenous peoples and diverse groups of people; strong communication, event-planning, and organizational skills; and who exhibit a high degree of professionalism and the ability to work in a self-directed environment or in a group setting.

In addition to the Communications Coordinator, the ILPC also includes a Director and Legal Counselor. Center staff work closely to support pathway to law programs, recruit students, provide services to students, provide teaching and learning opportunities related to Indigenous law, produce original research and scholarship on Indigenous law, and host educational events for MSU Law and other public audiences including members of Tribal communities. MSU College of Law is also home to an Indian Law clinic that coordinates in some areas with the ILPC.

The Communications Coordinator assists the ILPC team by providing administrative support. In collaboration with the College of Law Director of Events and the Director of Communications and Marketing, the Communications Coordinator supports the ILPC by planning events and managing ILPC internal and external communications for students, prospective students, alumni, scholars, Indian law practitioners, Tribal leaders, members of Tribal communities, the broader Law College, and MSU communities.

DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

Event Planning

- Fully coordinate and promote a two-day national Indian law conference co-hosted by the ILPC and the Tribal In-House Counsel Association (TICA) each fall for 28 speakers and 125 attendees.

- Plan an ILPC graduation event each spring.

- Plan biannual meetings of an ILPC tribal leader advisory group.

- Monitor ILPC events and conduct post-event reviews with ILPC staff.

- Coordinates lunches, speaking events, and ILPC visits for students interested in Indian Law.

- Plan and organize the annual ILPC conference: prepare annual event, communications, and marketing budgets.

- Plan monthly professional development and social events for ILPC students.

- Plan an ILPC welcome reception for students, faculty, and staff in the Native community at MSU College of Law, at MSU, and in the Lansing community.

- Plans other events aligned with the ILPC’s needs and strategic initiatives.

Communications, Marketing, and Outreach

- Draft ILPC correspondence and create newsletters for the ILPC community, students, and alumni.

- Draft and distribute a weekly internal newsletter for ILPC students informing them of upcoming ILPC events and other professional opportunities in Indian law.

- Draft and distribute a periodic internal and external newsletter for ILPC students, alumni, Indian law scholars and practitioners, and the broader public which reports on ILPC events and updates from faculty, staff, students, and alumni.

- Manage ILPC social media accounts and create content for them based on ILPC news.

- Update the ILPC web site with information about our programs and curricular offerings.

- Contribute content, including job announcements, on Turtle Talk, the nation’s leading blog on federal Indian law and Tribal law on WordPress (www.turtletalk.blog).

- Manage marketing materials that amplify and strengthen ILPC presence at MSU, Michigan tribal communities, and within Indian country.

- Manage the design, ordering, and distribution of ILPC marketing materials for students, prospective students, alumni, and guest speakers.

- Create and implement an annual ILPC communications strategy.

- Conduct outreach and liaise with internal University departments and outside educational institutions, including a national network of law schools.

- Prepare other communications aligned with the ILPC’s needs and strategic initiatives.

Office Administration

- Track and maintain the ILPC budget and submit ILPC expenses for reimbursement.

- Apply for grants from public and private sources to increase funding for ILPC events and strategic initiatives.

Travel

- Represent the ILPC at 1-4 recruitment events and Indian law conferences each year by coordinating and hosting an ILPC recruitment table at events (requires overnight travel).

Michigan State University College of Law is a diverse and inclusive learning community with roots dating to 1891 when it opened as Detroit College of Law in Detroit, Michigan. It moved to its current East Lansing location in 1995 and remained a private institution until 2020 when it became a fully integrated college of Michigan State University.

Today, MSU Law has more than 650 students, 55 faculty members, 50 staff members, five librarians, and a world-wide network of some 11,500 alumni. MSU Law operates seven legal clinics overseen by nationally recognized faculty that provide students an opportunity to work on actual legal cases. Additionally, it offers some of nation’s leading law programs in new and emerging legal education, including Intellectual Property and Trial Advocacy, Indigenous Law and Policy Center, the Lori E. Talsky Center for Human Rights of Women and Children, Conservation Law Center, and Animal Legal and Historical Web Center.

MSU College of Law, operating under the principles of its Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Strategic Plan, is poised to become the state’s preeminent law school, preparing a diverse community of lawyer-leaders to serve diverse communities in Michigan and beyond. It is committed to providing a legal education that is taught by leading scholars in their fields, includes best-in-class experiential opportunities, and helps students graduate without excessive debt.

Unit Specific Education/Experience/Skills

Knowledge equivalent to that which normally would be acquired by completing a four-year college degree program in Communications, Telecommunications, Journalism, Marketing, or Public Relations; up to six months of related and progressively more responsible or expansive work experience in internal communications; news, broadcasting, and print media, and/or marketing, advertising, and creative services; graphic design; word processing; desktop publishing; web design; presentation software; spreadsheet and/or database software; public presentation; or radio production; or an equivalent combination of education and experience.

The Indigenous Law & Policy Center (ILPC) and the Tribal In-House Counsel Association (TICA) Announce that Registration is Now Open for the 20th Annual Indigenous Law Conference

November 9-10, 2023 at MSU College of Law in East Lansing, MI

https://www.indigenouslawconference.com/

Click here for the agenda.

MSU Law is hiring in Indigenous Law

Michigan State University College of Law is hiring in Indigenous law. Entry-level and lateral tenure-system faculty members are invited to apply. Our announcement is below:

MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LAW

Michigan State University College of Law seeks to fill several tenure-system and fixed-term faculty positions for the 2024-2025 academic year. We welcome applications from candidates across all areas of law, but are particularly interested in hiring: (1) a tenured faculty member with exceptional teaching and scholarship credentials to fill our John F. Schaefer Chair in Matrimonial Law; (2) an entry-level or lateral tenure-system faculty member to join the Indigenous Law and Policy Center; (3) an entry-level or lateral tenure-system faculty member to fill the Inaugural 1855 Professorship in the Law of Democracy, which will focus on legal inequities in the democratic process and election law; (4) several entry-level or lateral tenure system faculty members to teach in one or more of the following subject areas: Trusts and Estates, Civil Procedure, Family Law, Commercial Law, Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure, Torts, International Law, Constitutional Law, and Professional Responsibility; (5) an entry-level or lateral tenure-system or fixed-term faculty member to direct the Low-Income Taxpayer Clinic; and (6) a fixed-term faculty member to teach in our Legal Research, Writing, and Advocacy program. Michigan State University is the nation’s premier land grant university, established in 1855. MSU Law’s history dates to 1891. More information about the Law College can be found at www.law.msu.edu. MSU is committed to achieving excellence through diversity. The University actively encourages applications from and nominations of people from diverse backgrounds including women, persons of color, people with diverse gender identities and sexual orientations, veterans, and persons with disabilities. Please submit application materials to MSU College of Law Faculty Appointments Committee Co-Chairs, Professor David Blankfein-Tabachnick dbt@law.msu.edu and Professor Brian Kalt kalt@law.msu.edu.

Kristen Carpenter article on “Aspirations”: The United States and Indigenous Peoples’ Human Rights

This article, published in the Harvard Human Rights Journal, is available here.

Abstract

The United States has long positioned itself as a leader in global human rights. Yet, the United States lags curiously behind when it comes to the human rights of Indigenous Peoples. This recalcitrance is particularly apparent in diplomacy regarding the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2007, the Declaration affirms the rights of Indigenous Peoples to self-determination and equality, as well as religion, culture, land, health, family, and other aspects of human dignity necessary for individual life and collective survival. This instrument was advanced over several decades by Indigenous Peoples themselves as a means to remedy the harms of conquest and colonization, along with legacies of dispossession and discrimination persisting to this day. The United States first voted against the Declaration in 2007, and now, having reversed that position, is still stuck behind international organizations and governments that are working to implement it. The examples are myriad. From a new infrastructure at the UN to legislation in Canada, Mexico City, and the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the world community is dedicating itself to realizing the aims of the Declaration. Not so the United States. In international meetings, U.S. representatives diminish the Declaration’s legal status when they could be embracing it as a vehicle for human rights advocacy; sharing best practices to and encouraging others to follow suit. At home, federal lawmakers are ignoring the calls of tribal governments to start implementing the Declaration in domestic law and policy. Increasingly, these positions of the United States are difficult to reconcile with respect for the dignity of Indigenous Peoples, much less global human rights leadership. Thus, it is time for the United States to abandon the notion that Indigenous Peoples’ human rights are “aspirational” and instead embrace the legal, political, and moral imperative to advance the Declaration both at home and abroad.

You must be logged in to post a comment.