Here are new materials in Metlakatla Indian Community v. Dunleavy (D. Alaska):

Prior post here.

Here is today’s order list, with an opinion by Justice Gorsuch (joined by Justice Thomas) dissenting from the denial of certiorari in Veneno v. United States:

Briefs:

Petition for Certiorari – Veneno

This is hardly a surprise given that both judges were critical of the Kagama decision. One presumes they come at this issue with a far different eye toward the outcome. Justice Thomas dissented in Brackeen because he found little constitutional text authorizing Congress’ Indian affairs powers. Thomas has seemingly sought an endgame to Indian affairs by attacking Congressional powers and tribal sovereignty. Justice Gorsuch found plenty of Congressional Indian affairs power in the text and structure of the Constitution, but not “plenary power” as described by the Kagama Court. His views are seemingly more in line with scholars like Bob Clinton, who saw no Congressional power to regulate the internal governance of tribal nations.

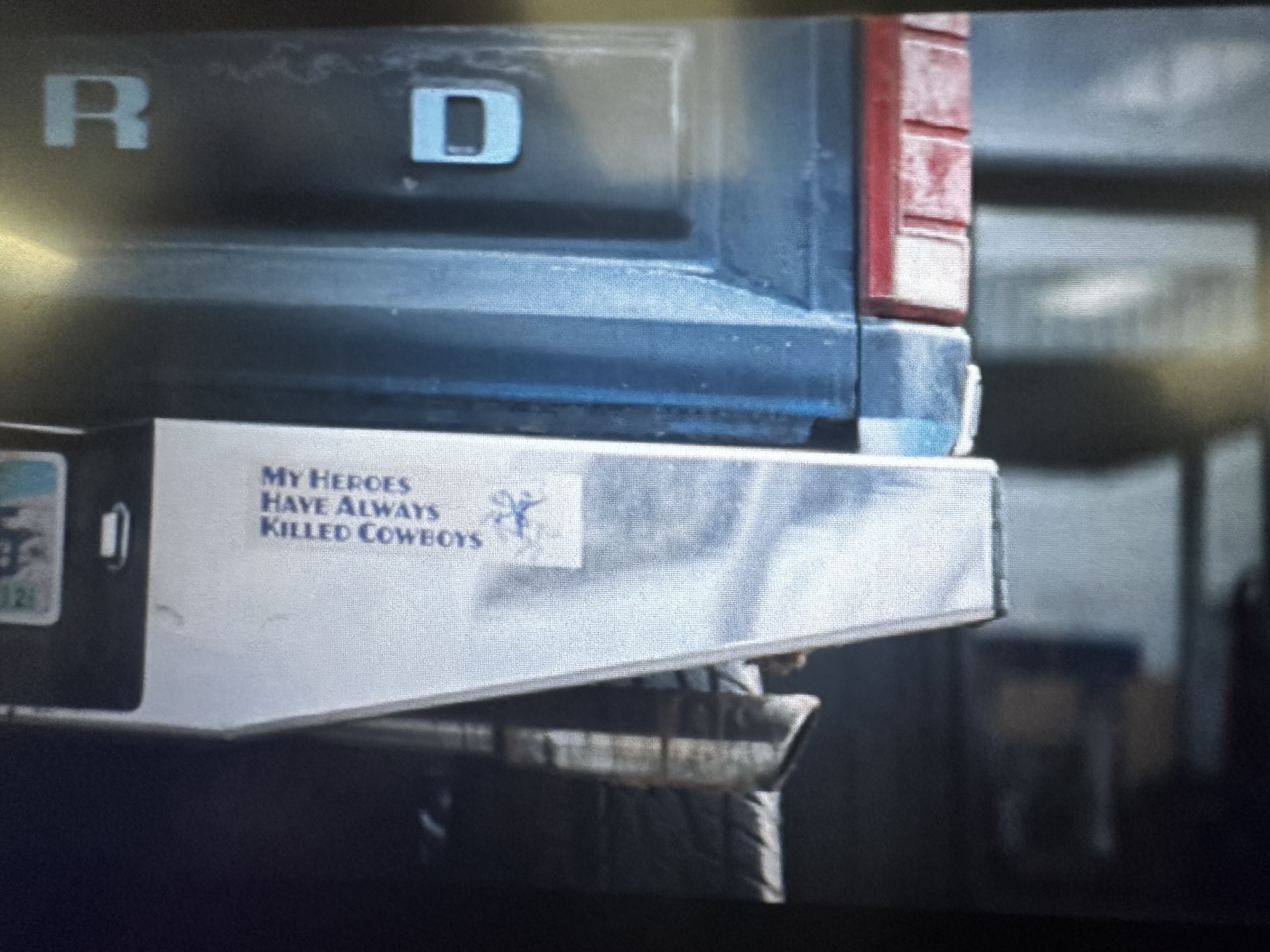

Certainly on a superficial level, who can really like Kagama? After all, the Court’s characterization of Indian people is unbelievably racist. It’s formalistic reading of the Constitution is also pretty . . . well, formalistic. There are important things in Kagama though, such as the notion that Congress possesses at least some powers by virtue of the duty of protection. Kagama is largely a dead letter anyway, since the Court has essentially already adopted Justice Gorsuch’s view of Congressional powers (e.g., Negonsott v. Samuels and U.S. v. Lara).

If these judges get their way and the Court eventually accepts a vehicle to review Kagama, for judges like Gorsuch, it might be merely housecleaning, but for judges like Thomas, it’s a potential revolution. There is ever-present the conflict between a formalist (Thomas) and a functionalist (Gorsuch) reading of the Constitutional text. I will continue to worry if the Court decides it needs to address Kagama if that’s the framing. It would be odd if the Court decided it needed a case to clean up its jurisprudential mess — full employment for Indian law profs!!! — where the law is settled.

More worryingly (perhaps?), the vehicle to reassess Kagama can only really be a federal criminal case. A vehicle like that will not be a good one to set the boundaries of Congressional authority over tribal nations, but instead a vehicle for revisiting Brackeen’s Congressional powers holding.

In the end, it’s just these two, so don’t hold your breath.

Here is the order in Tarabochia v. Quinault Indian Nation:

Do you know any students considering law school? Send them our way! The Indigenous Law & Policy Center at Michigan State University, in collaboration with the MSU College of Law Admissions & Financial Aid office are hosting a webinar on Tuesday, November 11 at 7PM EST.

The webinar, JOURNEYS TOWARD JUSTICE: INDIGENOUS LAW AT MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LAW will discuss the Indigenous Law & Policy Center at MSU Law. Featuring Prof. Wenona Singel, Director of the ILPC, and Kimberly Wilkes, Director of Admissions & Financial Aid. Additionally, hear from current students and recent graduates to hear about their experiences at MSU.

Please register at https://bit.ly/IndigenousLawMSU

Hope to see you there!

You must be logged in to post a comment.