Here is the opinion in Oenga v. Givens:

Here are materials from McClure v. Futrell (D. Mont.):

Throughout 2026, and in partnership with the America 250-Ohio Commission, the City Club will commemorate the 250th anniversary of the United States by exploring all the ways that Ohio has contributed to U.S. history for 250+ years. In January, our state will recognize the unique contributions of Ohio’s firsts and originals.

Since day one, and throughout the entirety of our country’s formation, Native Americans served as defining threads – and participants – in U.S. politics. Article 1, Section 8 (also known as the “Indian Commerce Clause”) in the U.S. Constitution establishes a unique federal-tribal relationship, acknowledging tribal sovereignty and self-governance. Today, it serves as the backbone for federal Indian law, which spans hundreds of years, impacting both tribal and non-tribal communities. What are the landmark moments in history that influenced the trajectory of our nation, particularly in the Great Lakes region? And how are modern Native Nations influencing the growth of the United States today?

Matthew L.M. Fletcher is a leading tribal law expert, and is the Harry Burns Hutchins Collegiate Professor of Law and Professor of American Culture at the University of Michigan. He teaches and writes in the areas of federal Indian law, American Indian tribal law, Anishinaabe legal and political philosophy, constitutional law, federal courts, and legal ethics. He sits as the chief justice of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, and the Poarch Band of Creek Indians; as well as an appellate judge for many other tribal nations. Fletcher also co-authored the sixth, seventh, and eighth editions of Cases and Materials on Federal Indian Law and three editions of American Indian Tribal Law, the only casebook for law students on tribal law.

Join us as we kick off our year-long America 250 series with University of Michigan Law Professor Matthew L.M. Fletcher. He will sit down in conversation with the City Club’s own Cynthia Connolly for an honest conversation on prior and continued contributions of Native American Nations and the making of the United States.

If you have a new announcement, please share it with us by uploading the information requested on this Google Form. If you have any questions, please email the MSU College of Law Indigenous Law & Policy Center at indigenous@law.msu.edu.

Save California Salmon, Hybrid (Remote/In-Person) Sacramento, CA

Save California Salmon (SCS) is seeking a Legal Coordinator/Staff Attorney to join our Policy Team. The Staff Attorney works directly with SCS’ Executive Director and legal, education and policy teams to review, analyze, and draft comments, policies, appeals, and litigation for SCS campaigns and issues and ensure compliance with all non-profit legal requirements. The Staff Attorney is responsible for overseeing any litigation, appeals, or legal hearings that the organization engages in, and also provides legal support and analysis to assist SCS in fulfilling its purpose. The Staff Attorney may provide oral public comments, provide policy analysis, draft written comments for various existing and proposed water projects, organize and attend coalition meetings, and serve as a media spokesperson on policy or legal issues.

Required Qualifications*:

Law degree and license to practice law from the California Bar Association, or ability to acquire CA Bar certification within a year

1-3 years of experience working in water, science and Indigenous rights policies and their implementation, preferably in California. Long-term internships can be applied.

Knowledge of California water, land, and Indigenous rights laws and related agencies

Knowledge of federal environmental and Tribal law

Experience writing scientific and policy related documents or analyzing these documents

Proficiency with Google Suite and strong computer skills

Excellent written and verbal communication skills

High level of attention to detail and ability to manage multiple projects simultaneously

Experience working with Tribes, Tribal organizations and people

Must be both self-motivated and a supportive team player

Must be able to lift up to 20 pound boxes and drive for long periods of time

Must be able to travel within state

Experience with public speaking and giving testimony

Desired Qualifications:

2-3 years of legal practice in a relevant field

Experience developing trainings and teaching policy advocacy

Experience with legislative procedures

Experience in community organizing

Experience working with public agencies, Tribal and non-Tribal representatives and educational institutions

Experience in communications related to science and/or policy issues

Experience in storytelling with communities of color

* We recognize that exceptional candidates may not meet every qualification. We are open to training the right candidate who demonstrates a strong commitment to SCS’s mission.

Salary: $75,000 – 88,000 annually Open until January 20th, 2026 https://www.californiasalmon.org/employment

Earthjustice , Remote

Support litigation in federal and state courts to advance Earthjustice’s mission.

Conduct administrative advocacy before federal agencies and state and local governments.

Develop and execute other types of advocacy campaigns in collaboration with other

Requirements:

Juris Doctor (JD) degree.

Active bar membership in working location.

5-7 years of litigation experience.

Experience in and understanding of Federal Indian law, tribal law, and environmental law. Salary: $140,200 – 175,500

Interested candidates should submit the following materials via Jobvite. Applications submitted by 5:00pm PT on Sunday, February 1, 2026 will be given priority, and applications received after may be reviewed on a rolling basis until the role is filled. Incomplete applications will not be considered. https://app.jobvite.com/j?aj=o9WjzfwH&s=TurtleTalk

Dakota Plains Legal Services, Mission, SD

Like many long-standing institutions, Dakota Plains Legal Services is at an inflection point. After years of underinvestment, it now seeks a visionary, hands-on Executive Director to rebuild capacity, reinvigorate litigation and advocacy strategies, strengthen relationships with tribal nations, and lead the organization into its next chapter of impact and sustainability.

•J.D. and active license (or eligibility to become licensed) in South Dakota. South Dakota has reciprocity with many states.

•Significant experience in legal aid, public interest law, tribal law, or closely related fields

•Demonstrated leadership experience, including staff supervision

•Experience with or strong aptitude for fundraising and grant development

•Commitment to serving Native American communities and underserved populations

•Ability to work effectively with tribal governments and diverse stakeholders

Salary: $110,000-150,000 Open Until Filled https://www.nlada.org/node/87396

Environmental Law Institute, Washington, DC

The Climate and Energy Law Fellowship, a one-year position for a recent law school graduate junior attorney (with the possibility of extension), is a unique opportunity to contribute to research and education on various climate and energy topics. The Law Fellow will work primarily with the Institute’s Climate Judiciary Project (CJP), which educates judges about climate science, impacts, and solutions and how they are arising in the law. The Project partners with national, state, and academic judicial education institutions on events, produces training materials, and fosters a better understanding of science and the law in the judicial community.

The Law Fellow will work closely with other ELI attorneys and professionals to develop CJP curriculum materials, create educational content, and plan events. This will include researching and drafting materials related to the law and policy dimensions of climate change and the energy transition for publications and presentations. The Law Fellow will also contribute to the preparation, development, and delivery of presentations for in-person and virtual events. The Law Fellow may also, as needed, support ELI’s other climate and energy-related work. JD Salary: $65-70K per year Open until March 31 www.eli.org/employment

Hoopa Valley Tribe, Hoopa, CA

Senior Tribal Attorney is responsible for providing legal advice, representation, drafting, research, and opinions on a wide range of matters as requested by Tribal Administration, Tribal Programs, and Tribal Enterprises. Major responsibilities include: tribal policy development, legal research and drafting, review of business contracts and facilitation of economic development efforts, representation in civil and administrative proceedings, negotiations with local, state, and federal agencies, and other duties as assigned. Will also work closely with the Tribe’s legal team and other attorneys with whom the Tribe has contracted for specific additional legal representation. Administrative duties include: preparing annual departmental budgets, assisting the Hoopa Valley Tribal Council (and its various departments and entities) in allocating its legal resources in a cost-effective manner, supervising outside counsel, and hiring/managing Office of Tribal Attorney staff.

• Respectful, courteous, and friendly to the public, other tribal employees, and tribal leaders. A team player who helps the Tribal Council meets its objectives. Takes initiative to meet work objectives. Effective communications with the public and other tribal employees. Gets along with co-workers and managers. Demonstrates honesty and ethical behavior.

•Must have knowledge of Microsoft Word, Acrobat, Word Processing software and Excel Spreadsheet software.

•Establish and maintain effective working relations with the Tribal Council, Tribal Departments and/their Entities, Committees, Community, and outside resources with firmness, tact, and impartiality;

•Prepare and present effective oral and written informative material related to the activities of the Hoopa Valley Tribal Council. This will include technical writing and presentations to diverse audiences;

•Ability to analyze complex problems and situations and to propose quick, effective, and reasonable courses of action;

•Ability to organize information (maintain organized files, notes, and records) and be able to organize, and plan multiple tasks and projects;

•Ability to check, analyze workload/caseload to determine effectiveness and determine future needs.

•Must have supervisory experience.

•Must be a graduate of an A.B.A. approved Law School; Juris Doctor (JD) Degree. Must be licensed to practice law in any state of the United States, preferably California, and obtain admission to the Hoopa Valley Tribal Court Bar. At least four (4) years of experience practicing Federal Indian Law or providing legal services to Tribal Governments.

Salary: 140,000/ Annually Open until February 2,2026 https://www.hoopa-nsn.gov/tribal-jobs/

A Tuition-free training brought to you by the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians & OJS Tribal Justice Support

March 4-5, 2026

Starting at 9:00 am

Seven Feathers Casino & Resort, Canyonville, OR

Here:

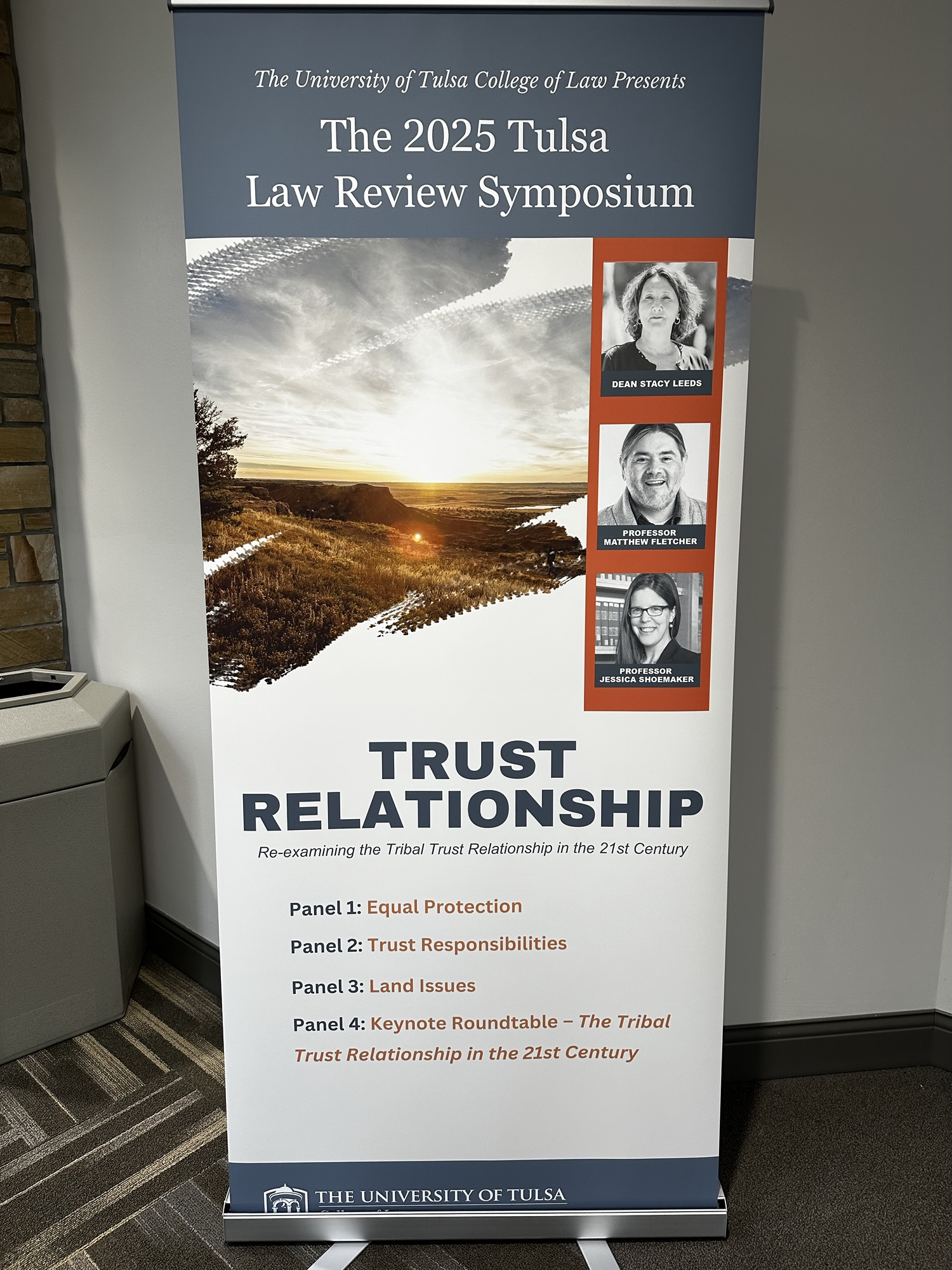

Fletcher’s Uncertainty Principle

Matthew L.M. Fletcher

Tribes as Nations: The Future of the Trust Relationship

Adam Crepelle

The Unenforceable Indian Trust

Ezra Rosser

The New Existentialism in Indian Law

M. Alexander Pearl

Fractionation by Design: Remedy Without Repair in Indigenous-Owned Trust Allotments

Jessica A. Shoemaker

Tribal Co-Management on Ceded Lands: A New Era?

Michael C. Blumm and Adam Eno

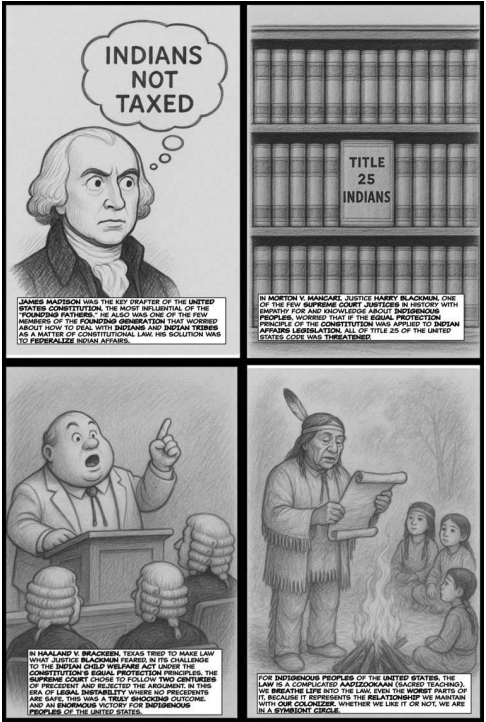

Original Comic: Tribal-Federal Symbiosis—An Aadioozaan

Matthew L.M. Fletcher

Here:

Here:

Questions presented:

1. Whether the Indian Commerce Clause preempts state regulation of loans made on an Indian reservation, by an arm of a tribe, when the borrower contracts via the internet.

2. Whether a violation of the unlawful debt prohibition of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1962, requires scienter for civil liability.

Lower court materials here.

Here is the opinion in United States v. Murphy.

The defendant was the subject of Sharp v. Murphy, the predecessor case to McGirt v. Oklahoma.

You must be logged in to post a comment.