Kristen A. Carpenter has posted “A Human Rights Approach to Cultural Property: Repatriating the Yaqui Maaso Kova,” forthcoming in the Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal, on SSRN. Here is the abstract:

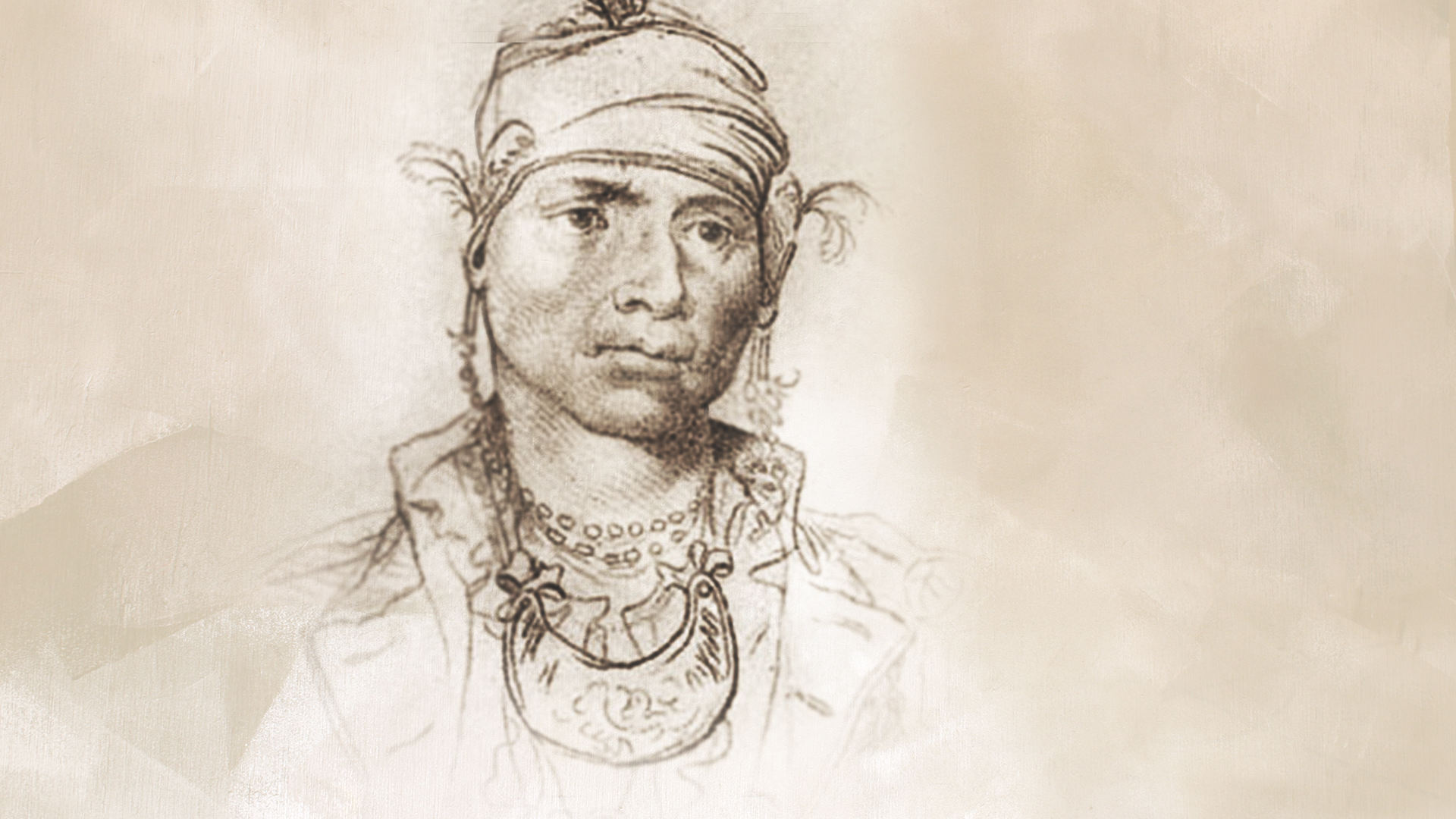

Claims for repatriation of cultural property are emerging across the international community, with increasing attention to the inequities of acquisitions made during colonial periods. Yet the State-centric nature of legal instruments, such as the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property of 1970, remains a stumbling block to advancing meaningful remedies for past harms, especially in the Indigenous Peoples’ context. States often pursue repatriation to advance national identity or replenish museum collections, but for Indigenous Peoples, repatriation often has to do with restoring dignity to ancestors through reburial, returning ceremonial objects to religious use, and healing the community from cultural assimilation and oppression. Against this backdrop, the essay reviews the recent case of the Yaqui People, an Indigenous nation spanning the U.S.-Mexico border, who negotiated a pathbreaking agreement to repatriate a sacred deer head, the Maaso Kova, from the national museums of Sweden. Working with the United Nations Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the parties expressly invoked the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, along with Yaqui and Swedish law, as bases for repatriation. The Yaqui-Sweden matter advances a human rights approach to repatriation that begins to transcend the hegemony of States in cultural property claims, while recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ equality and self-determination, along with religious and cultural freedoms.

You must be logged in to post a comment.