Here are the materials in State of Ohio ex rel. Ohio History Connection v. Moundbuilders Country Club Company:

Prior post here.

NYTs coverage here.

Here are the new materials in Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town v. First National Bank and Trust (E.D. Okla.):

Prior post here.

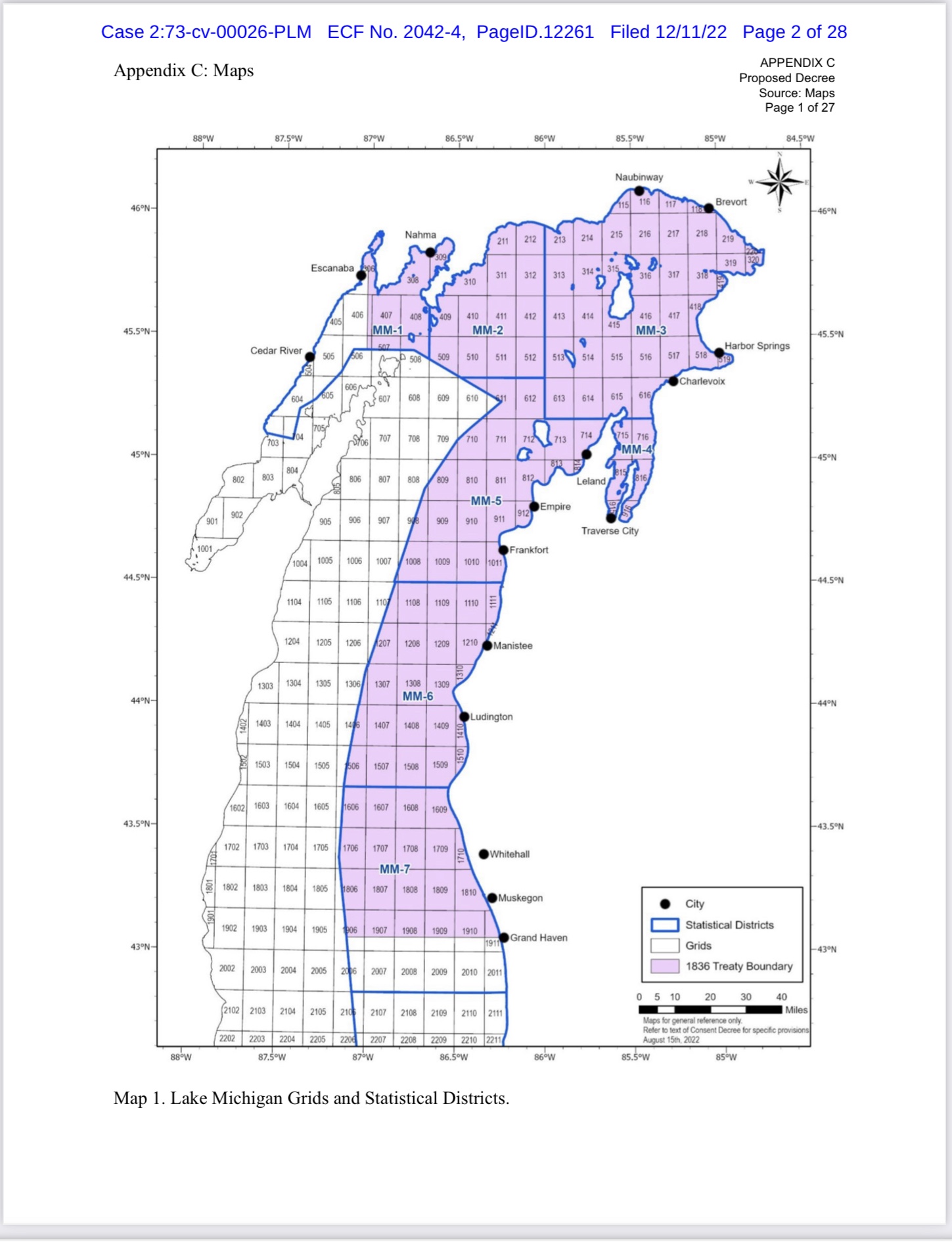

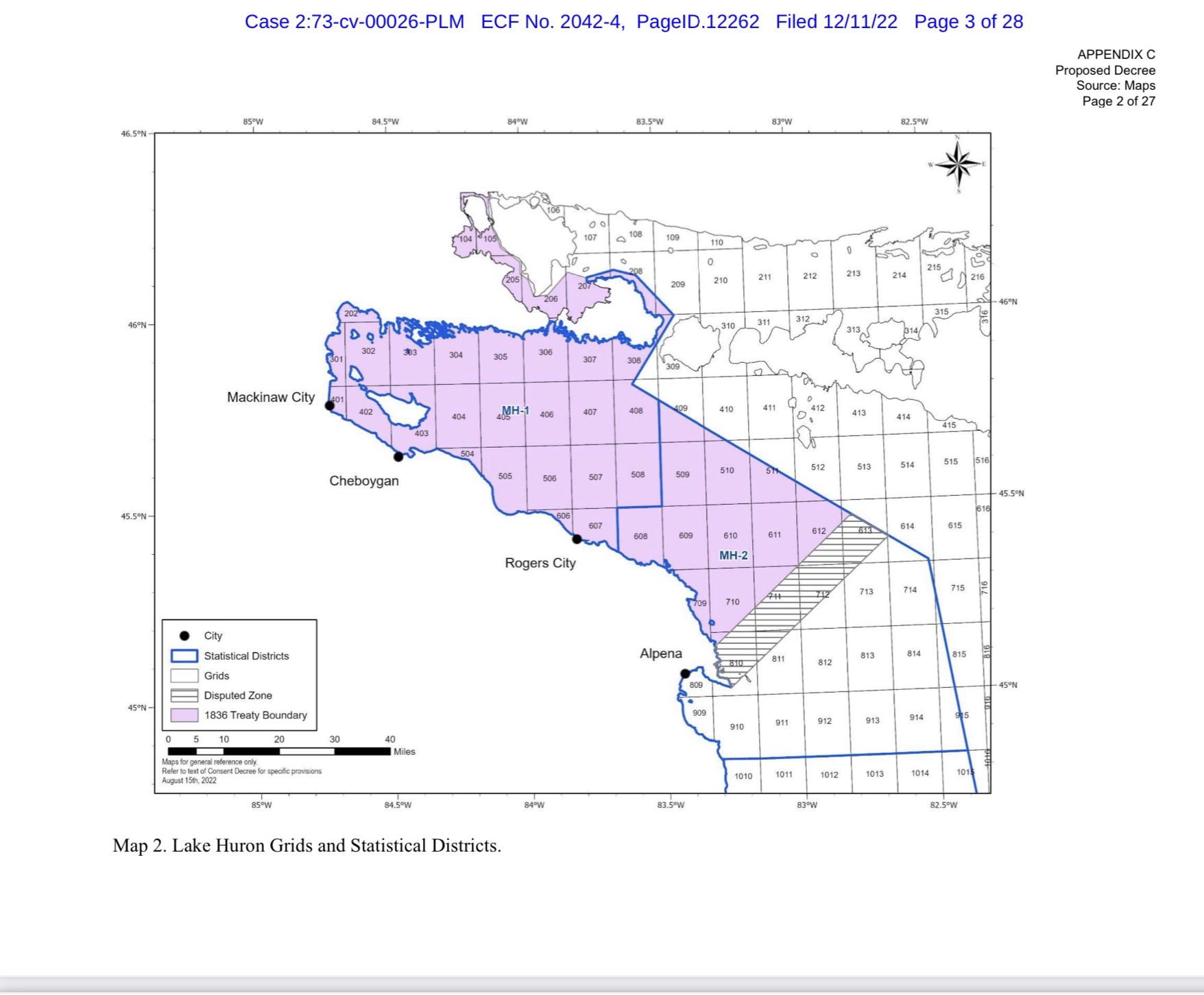

Here are the materials in United States v. Michigan (W.D. Mich.):

Here is today’s order list.

The denied petition is Big Horn County Electric Cooperative Inc. v. Big Man.

Neoshia Roemer has posted “Un-Erasing American Indians and the Indian Child Welfare Act from Family Law,” forthcoming in the Family Law Quarterly, on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

In 1978, Congress enacted the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) as a remedial measure to correct centuries-old policies that removed Indian children from their families and tribal communities at alarming rates. Since 1978, courts presiding over child custody matters around the country have applied ICWA. Over the last few decades, state legislatures, along with tribal community partners and advocates, have drafted and enacted state ICWA laws that bolster the federal ICWA laws. Despite four decades of ICWA, trends in child welfare demonstrate that Indian children are still vastly overrepresented in the child welfare system. Because tribal communities, advocates, community partnerships, and scholars work tirelessly to both ensure and improve ICWA compliance, ICWA still provides some of the best outcomes for Indian children through both family reunification and/or placement within their tribal communities.

However, family law often minimizes or mischaracterizes what the Act does. While ICWA is a complex law and even an entire semester may not fully provide justice to the breadth of the Act, this characterization of ICWA creates a stigma around the law. Family law scholars and practitioners can no longer overlook ICWA in conversations and teachings. Stigmatizing ICWA in the classroom contributes to the erasure of American Indians from our society at large and from our classrooms. This allows legitimized racism against this community to seep into both the classroom and the practice area.

Accordingly, this article discusses how family law classrooms can incorporate ICWA into conversations on family law as a step in eliminating bias in the legal academy and in the profession against American Indians. This article describes some of the history around ICWA, how family law feeds into the erasure of American Indians in the legal field, some misconceptions about ICWA, and how we can tie ICWA and other issues impacting American Indians into our classroom teachings on family law.

Please check out “The Dark Matter of Federal Indian Law: The Duty of Protection,” a draft of which is now available on SSRN.

Here is the abstract:

The United States and every federally recognized tribal nation originally entered into a sovereign-to-sovereign relationship highlighted by the duty of protection, a doctrine under international customary law in which a larger, stronger sovereign agrees to “protect” the small, weaker sovereign. The larger sovereign agrees to this duty of protection, in the American case anyway, in exchange for massive, occasionally unquantifiable amounts of land and resources, as well as the power to control the external sovereign relations of the protected sovereign. The smaller sovereigns, in this case, tribal nations, typically received protected reservation lands, hunting and fishing rights, small cash infusions, and the vague promise of protection.

What tribal nations have received so far in exchange for their lands and resources and sovereignty is a pittance compared to the value of that consideration. Justice Gorsuch noted in a recent case that tribal nations in Washington gave up millions of acres in exchange for “promises.” Those promises must mean something.

I call those promises the dark matter of federal Indian law.

The duty of protection owed by the United States to tribal nations is much like dark matter. The duty of protection was left undefined in Indian treaties. Yes, the treaties and other agreements that established a sovereign-to-sovereign relationship did provide for specific details about that relationship, most famously hunting and fishing rights or criminal jurisdiction. But most treaties and agreements are sparse, leaving open most of the details about that relationship. That’s the dark matter of Indian law.

This essay argues that the duty of protection between tribal nations and the federal government is law and that the judiciary has an obligation to enforce aspects of the duty of protection as understood by both tribal nations and Congress. The essay begins by describing the duty of protection as understood by tribal nations at the time of the origination of the duty and now. The essay then turns to how Congress and the Department of the Interior understands the duty of protection, at least since the start of the tribal self-determination era in the 1970s, and how the Department of Justice often undermines that understanding. Then, the essay explains that the dark matter of federal Indian law is the duty of protection, that the federal obligations to tribal nations and individual Indians is real, and that the duty of protection is enforceable. Finally, the essay shows how the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is a useful tool judges can use in adjudicating the scope of the unstated parts of the duty of protection.

This essay is an invited submission to the Maine Law Review Indian law symposium.

This paper was also the subject of the 2022 Rennard Strickland lecture at the University of Oregon Law School:

Payment v. Election Committee

Hoffman v. Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians Board of Directors

MacLeod v. Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians

You must be logged in to post a comment.