Here is the complaint in Vanir Construction Management v. Gray (D. Idaho):

Related case.

Here, authored by Kieran Murphy. PDF

An exceprt:

First, tribal courts are not, as Judge Bumatay suggested, “subordinate to the political branches of tribal governments.”68 For support, Judge Bumatay cited to Duro v. Reina,69 which cites to the 1982 edition of Cohen’s Handbook of Federal Indian Law.70 But tribal courts have changed since 1982: The 2024 edition of Cohen’s Handbook states that “[t]he structure of tribal courts is often similar to that of state courts” and “[p]rinciples of judicial independence have strong and growing roots in tribal courts.”71 Increasingly, tribes are “professionaliz[ing] the[ir] judiciar[ies]” in ways that “insulate them from tribal political pressure.”72

The Suquamish Tribe itself is illustrative. Judges are appointed by the Suquamish Tribal Council, which may alter judges’ powers or set salaries only at the time of judicial appointment.73 And judges are removable by a two-thirds vote of the Tribal Council, but only for “misfeasance in office, neglect of duty,” “incapacity,” or “convict[ion] of a criminal offense.”74 Judicial independence is thus a central feature of the Suquamish judiciary, as it is in many tribal courts.

Next, contra Judge Bumatay’s assertion that “tribal courts don’t rely on well-defined statutory or common law” but on values “expressed in [their] customs, traditions, and practices,”75 tribal law is “written, knowable, and publicly available.”76 Tribal constitutions, codes, and judicial opinions, including those of the Suquamish Tribe, are available from tribal governments, often online.77 While it is true that some tribal courts use traditional, nonadversarial practices to resolve internal disputes,78 those courts do not typically apply them to nonmembers, but instead use common law from the Anglo-American tradition.79 And tribes have little incentive to apply unknown or unfair tribal law to nonmembers given the Supreme Court’s anxiety about that possibility.80

Finally, Judge Bumatay misunderstood tribal law when he wrote that “because the tribes lie ‘outside the basic structure of the Constitution,’ the Bill of Rights, including the rights of due process and equal protection, doesn’t apply in tribal courts.”81 As Judge Smith noted in her Suquamish Tribal Court opinion, the “Indian Civil Rights Act . . . guarantees the right of due process under the law.”82 Furthermore, “[t]he test for due process in tribal courts is no different than for state or federal courts.”83 Federal courts ensure that a tribal court’s exercise of personal jurisdiction over nonmembers complies with the Fourteenth Amendment.84 And the criminal procedure protections of the Bill of Rights are inapplicable, as tribal courts may not exercise criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians.85

Judge Bumatay specified only one constitutional concern: “[W]ithout any constitutional backstop, tribal suits are almost exclusively tried before tribe-member judges and all-tribe-member juries.”86 For support, he cited to a footnote in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe,87 which states that tribes are “not explicitly prohibited from excluding non-Indians from the jury” and that the Suquamish tribal code provides “that only Suquamish tribal members shall serve as jurors in tribal court.”88 But Oliphant does not say that tribal courts employ “almost exclusively . . . tribe-member judges and . . . juries.”89 To the contrary, many tribal juries do include nonmembers,90 while some do not rely on juries for civil cases at all.91 And tribes, including the Suquamish Tribe, regularly hire judges who are nonmembers or non-Indian altogether.92

Here are the materials in Town of Southampton v. Goree (N.Y. S. Ct.):

It is unfortunate that the court employed the City of Sherrill-based “equitable defenses” analysis here. That decision, which Justice Ginsburg later regretted writing, is one of the most casually cruel decisions in Indian affairs history. The notion that any tribal action that “disrupts” the “settled expectations” of the settlers could be summarily dismissed. Effectively, any disruption at all is enough, even if no one provided any real evidence of “disruption” (whatever that is). Filing a lawsuit is “disruption.” Given the utterly lawless and indeterminate Sherrill defenses, the court here made the following conclusions (not sure of law or fact, I guess both?):

Here, as in Polite, Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on their claim because “this case presents the type of disruptive land claim that would be barred under the doctrine of City of Sherrill” (Polite, 225 NYS3d at 141). As noted above, homeowners neighboring Westwoods are currently and will be adversely affected by the construction of the Travel Plaza. Further, there is a settled expectation on the part of the area residents that the Town would maintain Newtown Road in its present condition and would regulate the proper location of curb cuts, as well as ingress and egress to the Travel Plaza. There is a settled expectation that the roadway would not be cut into wooded lands in a residential rural area in order to permit access to the 20 pump gas station, smoke shop, retail, and convenience stores from the heavily traveled Sunrise Highway. There is a settled expectation of the neighboring residents that Westwoods would preserve its residential character, that there would not be thousands of additional motorists driving on Newtown Road and across the newly constructed road to access the Travel Plaza, and that there would not be a major commercial development in a residential zone that has been forested for centuries. There is an expectation on the part of the residents and homeowners that State and local laws will protect their health, safety and welfare by imposing site plan controls, which would likely require adequate buffers between their homes and the Travel Plaza.

I’ve written on tribal disruption several times (here is a representative sample) to show that the assumptions underlying Sherrill are empirically false. Moreover, there is no limiting principle to the Sherrill reasoning. Moreover (again), the “equity” analysis rejects any tribal nation’s interests in restoring its land, economic, and governmental bases, destroyed over decades or centuries of illegal and often downright evil acts of current settlers predecessors. Finally, Sherrill can and should be a dead letter given that the judiciary has turned to textualism. Oklahoma after all figuratively just screamed “Sherrill!” at the Supreme Court over and over again in McGirt, only to be turned away for not making arguments rooted in legal text — McGirt can and should be — must be — read as repudiating Sherrill.

The court’s recitation of the “settled expectations” of the settlers here is nothing more than a list of land use grievances akin to NIMBY complaints. We get, these non-Indians don’t want Indians around. That’s what the reasoning of Sherrill (and similar cases like Patchak I, where SCOTUS held that being angry about tribal casino construction was “injury in fact” for standing purposes) suggests, but those are simply policy preferences made “law” by judges and should have no jurisprudential value.

Here is “AI and Tribal Court Practice,” soon to be published in the American Journal of Trial Advocacy.

Here is an excerpt:

American Indian tribal court practice resides at the intersection of two difficult legal problems. First, because tribal justice systems are usually very young and dynamic, awareness and analysis of tribal law is underdeveloped. Second, because tribal nations are not governed by state or federal law, tribal law is culturally unique. Tribal court practitioners often find that even routine legal matters will involve questions of first impression in the jurisdiction. All of this is to say tribal court jurisprudence is intensely jurisgenerative.

Because tribal law is often unsettled or indeterminate, the costs of discovering and applying this law are occasionally high. Most tribal law involves tribal constitutional or statutory interpretation or the application of federal and state court precedents, which is not terribly costly to perform. But applying tribal customary or traditional law, also known as tribal common law, can be much more difficult. Today, legal practice is knee-deep in reliance on artificial intelligence (AI). More practitioners are using AI to conduct legal research and even to draft pleadings. Assuming a practitioner reasonably utilizes AI generators, the use of AI can be beneficial. One assumes that the larger the corpus of law (statutes, cases, regulations, etc.), the greater value AI can provide in cutting out the relevant legal wheat from the irrelevant legal chaff.

This Article offers preliminary thoughts on how tribal court practitioners can use AI to research and apply tribal law using a common legal issue—tribal sovereign immunity. This Article analyzes written research memoranda and pleadings generated by AI. As a result, this Article concludes there is great potential for the use of AI in tribal court practice, but there are definite and indefinite pitfalls.

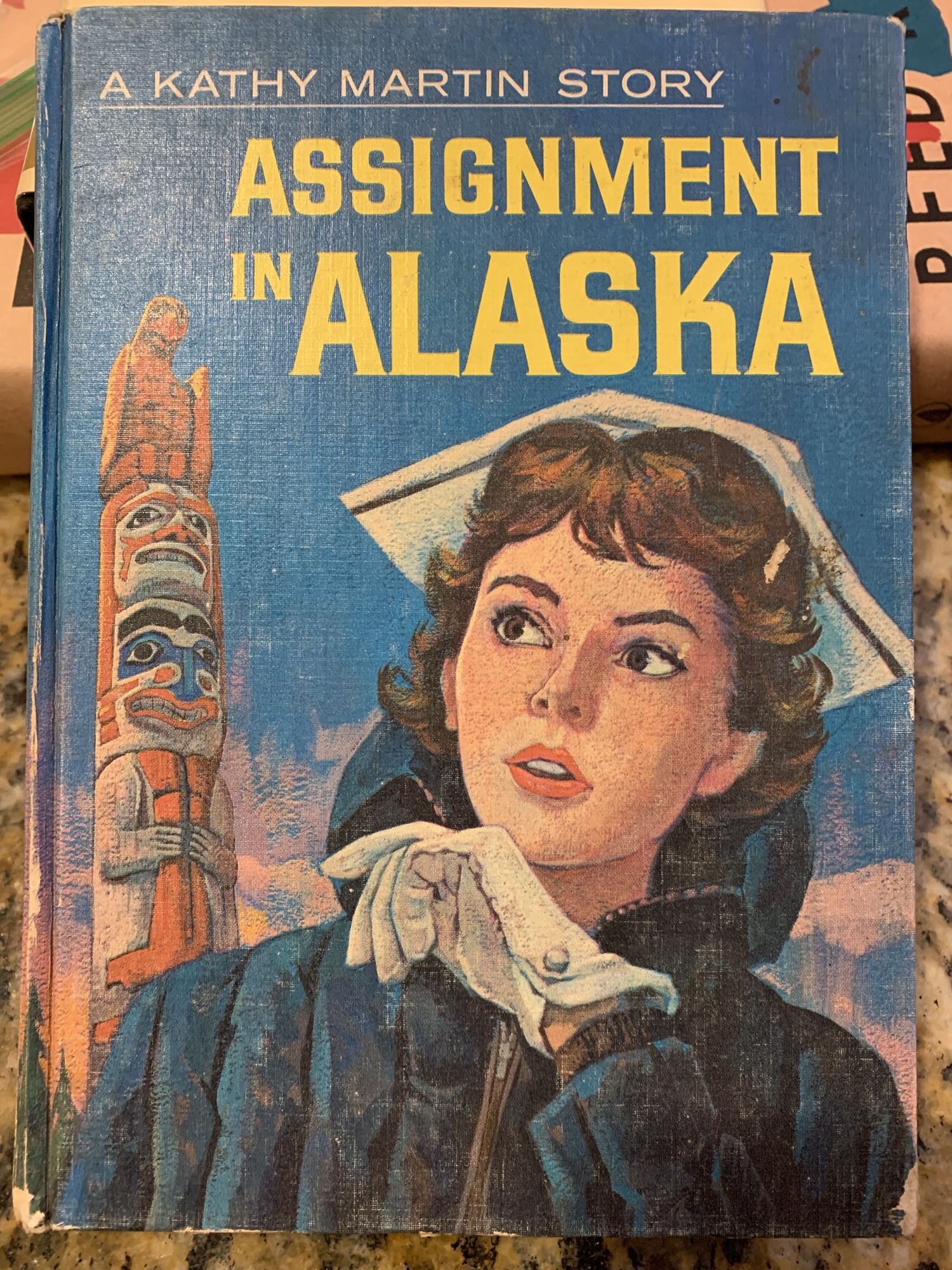

Here is the complaint in Village of Dot Lake v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (D. Alaska):

Aila Hoss has posted “Indigeneity, Data Genocide, and Public Health” in the Iowa Law Review. PDF

Here is the abstract:

Public health datasets will often tell us nothing about Indigenous people. This type of data suppression has been described as data genocide and data terrorism, because it demonstrates the effort to erase Indigenous people. Even when data is available, Tribes and their partners are regularly denied access to public health data from other jurisdictions. The seemingly simple call for more accurate, comprehensive public health data regarding Indigenous communities butts up against complicated issues. Who is considered Native and thus captured in Indigenous data? Why is Indigenous data regularly excluded from datasets? Who gets access to Indigenous data? These questions implicate federal Indian law, colonization, and Tribal sovereignty. So, while better quality data and improved data access are important goals, there is no way to bifurcate the need for public health data with the systematic racism embedded into the laws that impact the analyzing, collecting, and disseminating of this data. This Article aims to outline how Indigeneity interfaces with public health surveillance systems, in the context of both the collection of accurate data and the access to such data. It summarizes existing law and policy that define “Indian” under various frameworks and explores the challenges and limitations of defining Indian, particularly for the purposes of public health surveillance. This Article ends with a series of considerations regarding public health surveillance reform to better support Indian country.

Here are the applications for leave to appeal in In re Application of Enbridge Energy to Replace & Relocate Line 5:

Application for Leave to Appeal

Lower court materials here.

Here are the materials so far in Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians v. Burgam (D.D.C.):

You must be logged in to post a comment.